Inside

|

Budget 2011-12: The Long View

JYOTI RAHMAN Will there be a change in revenue generation in light of the new tax reforms, posits

On June 9, AMA Muhith submitted the third budget of the third Awami League government. In the weeks since, the budget has been much parsed and analysed. Instead of possibly repeating much of what has already been said, this piece takes a longer term view.

The government's first budget was framed against the backdrop of the worst global recession in generations, while the second budget was drafted as Bangladesh was positioning itself in the emerging economic order. This budget, coming in the mid-point of the government's term, should be judged not just against what its two predecessors achieved, but also on the implications it will have over the remainder of the government's term.

Encompassing the record of the government thus far and the outlook into the next few years, this piece analyses three issues: economic growth; development expenditure; and revenue. The picture that emerges is decidedly mixed. On the plus side, the economy shows remarkable resilience. But development expenditure remains of questionable quality and quantity, while the jury is still out on the lofty revenue targets.

Economic growth

Chart 1 shows economic growth projections in the three budgets. The first budget of this government, framed during the nadir of the Great Recession, anticipated a slowdown, even though the economy was still expected to grow faster than what was achieved during the 1990s. In the event, the economy proved much more resilient. Coming out of the recession, a strong acceleration was anticipated in the 2010-11 (FY11) Budget, with growth of 6.7% in the budget year, accelerating to 8% in 2013-14 (FY14).

Even though preliminary estimates suggest that the growth rate for FY11 was on target, forecasts have been revised down somewhat into the medium term in the latest budget. For FY12, the latest forecast is a growth of 7%, faster than what was thought two years ago, but slower than what was anticipated last year. The growth rate is still expected to accelerate, but not to 8% during the term of the current government.

What should we make of the latest projections?

Over time, economies grow because of two reasons: the number of workers increase, and each worker becomes, on average, more productive. Working age population (that is, those aged between 15 and 64 years) is a reasonable proxy for the number of workers available in the economy. According the United Nations Population Database, Bangladesh's working age population is expected to grow by 2.2% a year between 2010 and 2015. Assuming that the number of actual workers rise by a similar rate, and noting the margin of error around these estimates, we can still do a back-of-the-envelope calculation of the required surge in productivity (measure by GDP per working age person) if the latest budget forecasts are to come true.

For these projections to be tenable, productivity has to grow by over 5% a year by FY14. Bangladesh has never experienced that kind of productivity growth -- the fastest productivity growth on record was 4.5%, achieved in 2005-06. But this doesn't mean it can't happen. This requires productivity growth to accelerate by one percentage point over three years. That kind of acceleration has been achieved in the late 1990s, and again during the mid-2000s. Compared with those years, the workforce is better educated, and better connected with the rest of the world. So the productivity spurt is definitely possible.

On the other hand, it is widely accepted -- by the government, independent pundits, the private sector and international agencies alike -- that the country is suffering from severe infrastructure bottleneck, something that was not the case to the same extent in the earlier years. To address the infrastructure crisis, the FY10 Budget introduced the concept of Private Public Partnership with much hype. Three years on, very little of that hype has been translated into ground reality, even though the government continues to allocate funds for PPP measures.

Indeed, it's not just the PPP projects where the realisation has fallen far short of announcements. Qualitatively as well as quantitatively, the same criticism can also be made of development expenditure in general, which is discussed next.

Development expenditure

The FY10 Budget allocated 30,500 crore taka (4.4% of GDP, 2,060 taka per capita) for annual development programme (ADP). In the 2010-11 (FY11) Budget, ADP was set for 38,500 crore taka (4.9% of GDP, 2,560 taka per capita). The latest budget sets aside 46,000 crore taka (5.11% of GDP, 3,020 taka per capita) for ADP.

Every year, the record size of the ADP budget becomes the subject of an animated discussion that completely misses the point that one should expect record ADP budget for the simple reason that the economy and the country's population are both growing over time. Instead of focussing on the size of the announced ADP, the focus should be on how much is spent when and on what.

Let's start with how much is spent. In FY10, around 78% of the ADP budget was actually utilised. This realisation rate was considerably higher than what was achieved under the military-backed regime, but lower than what each of the past three elected governments managed (Chart 2).

Going forward, the government can try to emulate its achievement under the stewardship of the late SAMS Kibria in Finance Ministry and Dr MK Alamgir in Planning Ministry, when about 90% of the ADP funds were utilised. That record was possible because of proper scrutiny by the central ministries and heightened co-ordination with and monitoring of the line agencies. The result was high but realistic targets, which were regularly met.

Failing that ideal ADP realisation, the government can choose a 'second best' path where a large ADP is announced, with promises made to various constituencies, lobbyists and supplicants, all the while knowing that the marginal projects will be discarded in the implementation phase. If this 'second best' option is adopted, then a focus on the realisation rate is misplaced. Indeed, in this scenario, if the government feels compelled to fully implement the announced ADP, there is a risk that large sums of money will be spent on poor quality projects towards the end of the financial year.

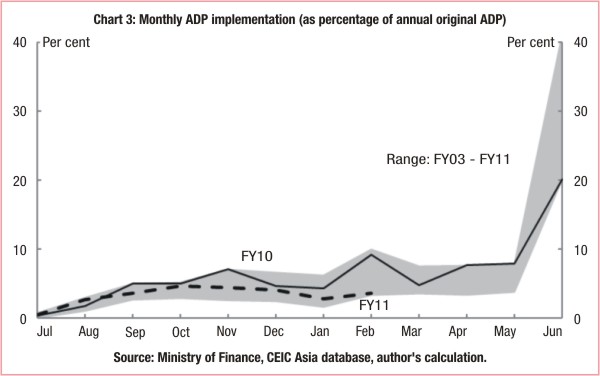

This then shifts the focus on when the sums are spent, which is illustrated in Chart 3. In this chart, the shaded area represents the range of monthly ADP implementation expressed as a percentage of the announced ADP since 2002-03. Typically, there is little implementation at the beginning of a financial year, while the month of June sees a bulk of sums spent (partly a reflection of end of year settling of accounts).

Ideally, ADP would be implemented in a way such that monies are spent steadily in the autumn, winter and spring months. A poor outcome, on the other hand, is when relatively little is spent in the post-monsoon months, and by the third quarter of the year there is a lot of commentary on how ADP remains underutilised, causing a wasteful spending spree in the final month of the year -- this is essentially what happened in 2003-04 and 2004-05, when around 40% of the funds were spent in June.

As the chart shows, compared with the past, the timing of ADP implementation under this government has, thus far, been rather mixed. While in FY10 the sums were spent fairly evenly throughout the year, the trends in FY11 has been among the worst in recent years.

Finally, there is the question on what the money is spent on. Of course, the choice of projects is the prerogative of the democratically elected government. However, the government's development partners, independent think tanks, and other stakeholders can and should scrutinise the appropriateness of the priorities made by the government. Instead of debating whether the ADP is too big or too ambitious, or calling for the 'best practice' project design that might be unattainable in our weak political and institutional culture, it would be better if the attention is focussed on making sure that right projects are implemented at the right time.

Revenue

Moving from the expenditure to the revenue side of the budget, the first thing that ought to be stated is that revenue-to-GDP ratio in Bangladesh has been far lower than other comparable economies in the region. This is not news. But it is always worth repeating the fact that our government does not collect enough revenue to pay for our teachers, nurses, and police officers, not to mention the public investment needed to achieve 7-8 per cent economic growth and cut poverty.

This much has been acknowledged by successive governments. And each government has followed a pattern of announcing a lofty ambition to raise the revenue-to-GDP ratio in the budget, only to fall short at the end of the year. For example, in the FY06 Budget, the late Saifur Rahman projected that total revenue would be 11% of GDP. In the event, the realised ratio was 10.3%.

One exception to this pattern was the military-backed caretaker regime, which achieved its budget target of 10.8% revenue-to-GDP ratio in 2007-08. Of course, that revenue generation was achieved under a state of emergency. And at this stage, it might be worth mentioning that it is possible to have significantly more revenue relative to the economy without draconian measures underpinned by radical political changes -- India raised revenue by 4% of GDP in the past decade, for example.

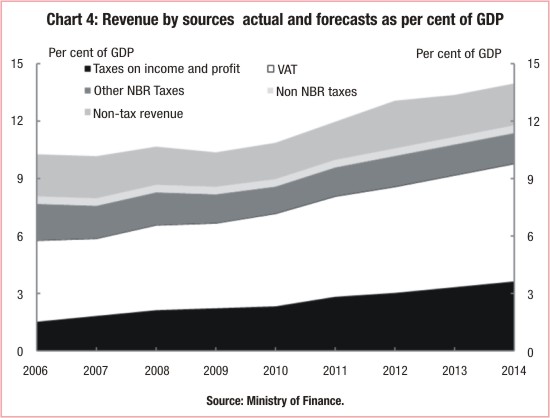

The current government seems to have reverted to the pattern of the last elected government. Thus, in the FY10 Budget, revenue-to-GDP ratio was set at 11.6%, while the outcome was 10.9%. Not deterred, the FY11 Budget raised the bar, with revenues projected to rise to 11.9% of GDP. And remarkably, this lofty target has been revised up to 12.1% f GDP in the revised Budget. Then, the forecasts are for further rapid rise in revenue relative to the economy, with income taxes and VAT projected to lead the revenue surge (Chart 4).

Will these lofty targets be met?

There may be grounds for optimism. The latest Budget does contain measures to expand the tax base, while significant reforms are being made to the tax administration system. But these are still small steps relative to what needs to be done. The history of revenue generation in Bangladesh is not an encouraging one. And the jury is still very much out on whether Mr Muhith will be more successful than his predecessors.

Jyoti Rahman is an applied macroeconomist and a member of Drishtipat Writers' Collective. He can be reached at Jyoti.rahman@drishtipat.org.