Inside

|

Khwaja Gul-e-Nur and Luce Irrigary:

Can the 'Woman' be a Subject without Cultural Specificity?

Divinity is what we need to become free, autonomous, sovereign. No human subjectivity, no human society has ever been established without the help of the divine.

-French Feminist Theorist Luce Irrigary, Divine Woman

It has been a common phenomenon in South Asian women's autobiographical writing to create a certain connection with the Divine in order to validate one's writing or justify one's female self. Rasshundari Debi (1810-1899) as early as 1860 wrote her memoir, and the central driving force behind her relentless effort to teach herself how to read and write was her desire to be able to read the holy and devotional scriptures. In her writing, as well as in the writings of legendary nineteenth century Bengali theatre actress Binodini Dasi's (1863-1941) , we find a trend of writing to the Divine, writing for the Divine, and finally writing in accordance, and with authority of the Divine.

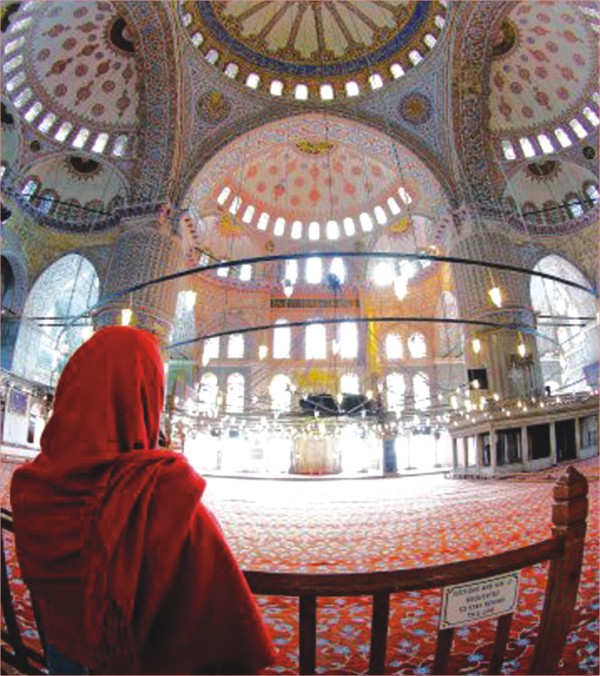

Photo: MICHAEL HITOSHI-GETTY IMAGES

The same pattern can be traced in the writing of twentieth century Bengali Pir-Ma, or Saint-Mother Khwaja Gul-e-Nur's personal writing, Amar Kotha or My Speech. Gul-e-Nur's writing is particularly interesting because, she not only consolidated the validity of her writing by creating connection with the Divine linage within the Islamic tradition, but her writing also stands as a testimony of her everyday material struggle to actively participate in shaping the spiritual-cultural-social structure of her husband Hazrat Khwaja Enayetpuri's Sufi Khanqa in the North Eastern region Bengal.

The social consequences of such writing is also crucial to explore because her memoirs later came to endorse the spiritual authority of her sons, and it dismantled the patriarchal value system and claimed a certain authority for the female self. Finally, by closely looking at her narrative one can actually map out Gul-e-Nur's spiritual, social and cultural journey in claiming her “free, autonomous, sovereign” self.

Gul-e-Nur was born in 1879 and she lived a long life to be 103 years old when she left the earth. She was married at the age of nine. She became the disciple of Hazrat Shah Sufi Wazed Ali at the age of 11. Her husband was also the disciple of the same pir. When Hazrat Khwaja Enayetpuri, Gul-e-Nur's husband started preaching as a successor of Shah Sufi Wazed Ali, she participated in preaching the female disciples, and planned the structural development of their khanqa.

During her life she produced numerous pieces of writing in Bengali even though she never was part of any schooling except for the Arabic lessons she received from her mother-in-law. Her knowledge of Bengali was owed entirely to her own merit since she acquired her Bengali skills by learning from other girls of her age who had the opportunity to go to school. Amongst the poetry and biography of saints she produced, stands out, her personal writing titled 'Amar Kotha' (1941).

Claiming the female Divine: Khadija and Fatema

Though Irrigary discusses the possibility of conceptualising a female Divine entity in order to claim a female subject, her discussion revolves primary around Greek mythology, Christian and Hindu mythical icons; however, there is no discussion of the Islamic tradition in her discourse. In this respect, looking at Gul-e-Nur's writing is interesting because, as I will argue, she produces what could be seen as a model proposed by Irrigary in claiming a female Divine entity in order to claim a female subjectivity.

Even though Islam is perceived as a strictly monotheist religion by certain groups, Sufi devotional practices, those particularly common in South Asia, tend to designate very important and venerable positions to certain individuals within the Islamic lineage. These individuals are believed to have reached the level of fana-fi-Allah (the one who has annihilated his/her own existence into Allah), thus, attaining the muhabbat or love of these individuals is indispensable for any devotee embarked on the journey to finally reach the makam or station of fana-fi-Allah.

Though there is no God but One Allah according to Islamic theology, within the realm of Sufi spiritual and devotional practices, the elevation and veneration of individuals is widely practised in order to reach the final makam or station of fana-fi-Allah. Since in Islam Allah is without any attributes, any gendered or humanly ones included, the spiritually potent individuals of Sufi tradition could then be looked at as the Divine figures of Islam. Thus, when Gul-e-Nur writes, “no Sufi saint in the world will ever be able to attain even a morsel of the hidden spiritual knowledge (ilm-i-marifat) by discounting Fetema, the mother of this earth” she actually claims a female Divine figure for herself, a female figure within the otherwise patriarchal landscape of Islam, a “figure for the perfection of her subjectivity.”

Photo: RAFA ELIAS/GETTY IMAGES

Throughout her writing, the reader finds a constant thread of Gul-e-Nur aligning her own experiences with the experiences of her female predecessors. Her writing is a constant effort to claim for herself a spiritual and material female standpoint. If according to Irrigary, claiming a Female God means being able to reference one's gendered self to an infinite Divine entity, then, Gul-e-Nur's claim of Fatema as one of the most important and indispensable part of Islamic spiritual tradition is an effort to affirm the authority of female individuals such as Fatema within the landscape of Islamic spiritual thinking.

Gul-e-Nur not only introduces Fatema as an indispensable authority of Sufism, but she harps on the instrumental role of Khadija in shaping the prophet's spiritual and material life. In a long poem written as tribute to the union between Muhammad and Khadija, Gul-e-Nur writes, “She [Khadija] is the leader of all the females in the world and according to Allah's wish she is the emperor of all heavens.” Moreover, included in Gul-e-Nur's biography of Sufi saints, is the biography of Syeda Zahura Khatun, the daughter of Gul-e-Nur's Sufi master's master. Even though Syeda Zahura Khatun's father Syed Sufi Maulana Fateh Ali before leaving the world, instructed his disciples to continue their spiritual tutelage under his daughter, her spiritual authority was denied by many due to her social position as a woman. Her authority is reclaimed and established in Gul-e-Nur's writing, when she quotes Syed Sufi Maulana Fateh Ali bestowing his spiritual power and authority to his daughter. The biography goes further on to describe details of Syeda Zahura Khatun's married life and the social consequences of her being a woman, which in many ways restricted and hindered her journey as a Sufi preacher.

It is indeed noticeable that the other Sufi biographies produced by Gul-e-Nur do not give detailed accounts of personal matters, however, in the case of the female Sufis such as Syeda Zahura Khatun, very detailed analysis of the domestic and social context and its interplay with the spiritual matters is explored. One finds parallelism in her own life events with the biography she produced of Khadija and Syeda Zahura Khatun.

Gul-e-Nur, however, in her writing elevated the icons of Khadija and Fatema from the secondary positions of the Prophet's wife and daughter, and situated them as individual powerful icons within the Islamic spiritual landscape. Furthermore, Gul-e-Nur claims that, without adhering to the authority of Fatema the highest spiritual attainment is impossible. Gul-e-Nur draws a lineage from Khadija to herself, “mother to you I pray, may I remain at your feet as your servant for eternity.” However, one problem remains lingering between the lines of Gul-e-Nur's text, and that is the problem of her social position as a Bengali Muslim woman.

The social predicament of becoming a female subject

…Since she was a woman, common people and society were not aware of her spirituality and spiritual status.

-Khawaja Muzzamel Haq, Durre Ekta or Hidden Treasure

Where the feminine is experienced as space, but often with connotations to the abyss and night, while the masculine is experienced as time.

-Luce Irrigary, Sexual Difference

Gul-e-Nur's youngest son Khawaja Muzzamel Haq wrote a biography of his mother and titled it 'Durre Ekta' or hidden treasure. In his introduction we confront the social conditions, which despite Gul-e-Nur's spiritual powers kept her veiled as the hidden treasure of Islam. Gul-e-Nur's biography by her son, lists all her accomplishments and contributions in building up the material and spiritual structure of the Sufi khanqa, however, the text does not explore Gul-e-Nur's predicament of being born a Bengali Muslim woman during the end part of 19th century under a social and cultural backdrop where women were denied personhood. It is due to this social predicament that Gul-e-Nur is today remembered simply as 'Pir Ma' or saint mother, whereas, in her writing she relentlessly elevated Fatema and Khadija from the secondary roles of wives and mothers to individual supreme icons. Moreover, the first edition of her book where she claimed spiritual authority for herself is not published and distributed anymore. What remains is the socially acceptable second edition, thus, her parler femme, though saw the light of publication, soon had to retreat in the darkness due to the narrow social prescription imposed on Bengali Muslim women.

It must be noted that, it is the line of women that supported the writing and publication of Gul-e-Nur's texts. Her memoir was published by her daughter Khawaja Ferdousi Begum and in the first edition, in the footnote Ferdousi Begum writes,

“Now I do not have strength I will use your torch light,” these words of Hazrat Khawaja Enayetpuri (Gul-e-Nur's husband) is very significant. Through this metaphor he wanted to express that Pir-Ma had to carry the light of Khawaja Enayetpuri, and Allah has given her such strength. There is no dispute about the spiritual competence of Pir-Ma.

Gul-e-Nur's remembrance of her husband seeking to borrow her light, and the subsequent unpacking of this metaphor by her daughter is completely absent in the second edition. It seems, however much Gul-e-Nur and her female successors attempted to establish her authority, it was denied and wiped out from the mainstream spiritual landscape of Khawaja Enayetpuri's Sufi khanqa. Thus, the spiritual potency, dynamic personality, fierce and keen individualism of Gul-e-Nur is retained only in personal remembrances of family members. In the end, despite her efforts, Gul-e-Nur has been locked into the privacy of oral culture.

It is interesting to note that, Gul-e-Nur's journey to claim her autonomous female self through reuniting with the mythical mother Fatema, is similar to what Luce Irrigary proposes in order to rescue the female ancestry from the seducer, let it be Freud, Hades, or patriarchal Islamic social practices in the case of Gul-e-Nur. However, the binary dichotomy and phallocentric philosophical tradition that Irrigary proposes to dismantle, though useful in understanding the central subject of the 'man', where every 'other' subject is erased, is still not enough to understand the complicated socio-cultural and religious traditions that wiped out Gul-e-Nur's text even after her relentless effort to claim authority for the female self. Thus, when Irrigary inquires, “[C]an the word woman be subject? Predicate?,” the answers to her questions will have specific answers based on the female subject's geographical and temporal location. “What status does the word have in discourse?” will also have to be answered with specificity. As problematic as it is to claim one universal 'man' as the subject, it is equally problematic to assume that there exists one universal female subject for us to discover.

1. Sarkar, Tanika, Hindu Wife, Hindu Nation: Community, Religion and Cultural Nationalism, New Delhi, Permanent Black, 2001.

2. Bhattacharya, Rimli, My Story and My Life as an Actress. New Delhi: Kali for Women,1998.

3.Gul-e-Nur, Khawaja, Amar Kotha or My Speech in, Khatune Jaannat or Mistress of the Heavens, Pabna, Bangladesh, 1941.

4. Irrigary, Luce, Divine Woman in Joy, Morny, Poxon, Judith, O'Grady Kathleen, eds. French Feminists on Religion, London, Routeledge, 2002.

5. Haq, Khawaja Muzzamel, Durre Ekta, Pabna, Bangladesh, 1951.

6. Schimmel, Annemarie, Mystical Dimensions of Islam, University of North Carolina Press, 1975

7. Irrigary, Luce, Divine Woman in Joy, Morny, Poxon, Judith, O'Grady Kathleen, eds. French Feminists on Religion, London, Routeledge, 2002.

8. Irrigary, Luce, Divine Woman in Joy, Morny, Poxon, Judith, O'Grady Kathleen, eds. French Feminists on Religion, London, Routeledge, 2002.

9. Gul-e-Nur, Khawaja, Bhakti Upahar or Gift of Devotion, Pabna, Bangladesh, 1942.

10. Irrigary, Luce in Joy, Morny, Poxon, Judith, O'Grady Kathleen, eds. French Feminists on Religion, London, Routeledge, 2002.

11. Irrigary, Luce, Joy, Morny, Poxon, Judith, O'Grady Kathleen, eds. French Feminists on Religion, London, Routeledge, 2002.

Work Cited:

1. Bhattacharya, Rimli, My Story and My Life as an Actress,. New Delhi: Kali for Women, 1998.

2. Gul-e-Nur, Khawaja, Khatune Jaannat, Pabna, Bangladesh, 1941.

3. Gul-e-Nur, Khawaja, Bhakti Upahar, Pabna, Bangladesh, 1942.

4. Haq, Khawaja Muzzamel, Durre Ekta, Pabna, Bangladesh, 1951.

5. Joy, Morny, Poxon, Judith, O'Grady Kathleen, eds. French Feminists on Religion, London, Routeledge, 2002.

6. Joy, Morny, Poxon, Judith, O'Grady Kathleen, eds. Religion in French Feminist Thought, London, Routeledge, 2003.

7. Sarkar, Tanika, Hindu Wife, Hindu Nation: Community, Religion and Cultural Nationalism, New Delhi, Permanent Black, 2001.

8. Schimmel, Annemarie, Mystical Dimensions of Islam, University of North Carolina Press, 1975