Inside

|

Film policy in Bangladesh:

The Road to Reform

CATHERINE MASUD discusses the dying film industry

and the need and ways in

which to revive it.

During the past one year, Tareque and I had begun to seriously reevaluate the path that we were taking as filmmakers. All around us were signs that the crisis in the film industry had reached a critical phase, and it no longer seemed worthwhile to make films in a country completely lacking in any coherent film policy. We began to research the reasons for the crisis and possible solutions, and this paper is a synthesis of many of our findings. I dedicate it to Tareque's and Mishuk's memory: they who had dedicated their lives to cinema, had dreamt great dreams of cinema, and had died together as they were embarking on yet another odyssey for the sake of cinema.

|

Zahedul I Khan |

Over the years, there was so much that we shared together, and so much that we all struggled to change and achieve. In earlier times, much of the challenge we saw before us concerned embarking on and completing one film project or the other. But more recently we came to see that what we were doing was a futile exercise unless certain structural problems were addressed that concerned everyone living and breathing this art form that we call cinema. And what a peculiar art form it is, built from a succession of individual static frames, that through persistence of vision the human mind interprets as motion. These deceptively simple moving images, through an incredibly involved technological and creative process, are formed together to tell a story. So many talents must come together to properly utilise the potential of this art form -- good writing and storytelling skills, a strong sense of rhythm and music, an exceptional ability to visualise, a firm grasp of technology, a strong understanding of acting and the handling of artists, supreme managerial skills, not to mention, in the case of Bangladesh, endless patience and drive to overcome an absurd degree of political, bureaucratic and logistical obstacles. And this is just the filmmaking side of it. The other side is the tremendous effort and drive that are required to bring our films to our audiences -- after all, cinema is a mass medium, and what is the point of our art, unless we can reach out to the people for whom it was intended?

Film is also the only art form that requires a massive infrastructure and industry behind it, to generate it, and an industry before it, to reach out to its mass audience. Production on the one hand, and distribution and exhibition on the other. In Bangladesh, however, film is neither art, nor industry.

In Bangladesh, film is the nomoshudro of the arts. It is the lowest on the totem pole in a status conscious society. All the other major arts -- theatre, music, painting, literature -- have a national centre, film has none. Film is the artistic profession that no 'bhodro' family would tolerate their children entering. Hence the expression, 'filmer liney namsey' -- they came down to the film profession. Perhaps appropriately then, film is under the Information Ministry, rather than the Cultural Ministry, subject to draconian censorship policies and controls. It is viewed as a prosaic and factual means of transmitting propaganda on the one hand, and as a crude exercise in blood-and-guts-song-and-dance entertainment on the other. Only occasionally is there a breakthrough, an exception, to remind us that film is also art, but that is rare. As a nomoshudro art, retired films even have no proper burial ground. The National Film Archives, which I have elsewhere referred to as “The Killing Fields of Cinema”, has been in a permanent state of dislocation and mismanagement for the past 30 years. Through it, innumerable historic films and related materials have been lost or destroyed. Until the Film Archives has a proper permanent home, with proper facilities, it is no place to preserve your irreplaceable original works.

|

Zahedul I Khan |

As for the industry, whether on the production side of the Film Development Corporation, otherwise knows as FDC, or the exhibition side of the cinema halls, counter-productive and backward policies have led to their near collapse.

The situation for independent films is hardly better. Lack of proper local facilities force filmmakers concerned about quality to battle red tape to get their films processed in expensive facilities abroad. Once they return, they have to face the reality of having only a small handful of decent theatres to screen their films to their largely middle class audiences, mostly limited to the capital city. This is inevitably followed by a television premiere that is so crammed with advertising that no one has the patience or concentration to watch it.

In order to better understand the reasons behind the crisis of cinema in Bangladesh, we need to first take a closer look at the state of the industry today with a historical view to the genesis of this collapse. Why is it that Film Development Corporation (FDC), with its huge government investment in facilities, credit-based subsidies to commercial filmmakers and protectionist policies that keep Hindi cinema at bay at least from the theatres, unable to produce good quality entertainment? In recent times, one actor, Sakib Khan, was temporarily able to attract audiences to the halls again; but even audiences tired of him after the endless stream of repetitive trash emanating from FDC. Not only in terms of quality, but also quantity, FDC is failing fast. Twenty years ago, on average 80-100 films were produced per year, far ahead of Pakistan or any other country in the region except India. Today, that number is down to 30-40 films per year. Many of these films aren't even shot on 35mm, they're shot on digital video, and then crudely transferred to 35mm for release. The vast majority of “commercial” films are box office flops, hence the desperate practice of splicing pornographic “cut pieces” into FDC films. FDC, saddled with massive corruption and mismanagement, will never be able to pull itself out of this downward spiral on its own; rather it will take a thorough review of the policies of subsidy and protectionism to force any real change. Interestingly, when we look back to the early 1960's, a time when not only did the local industry have to compete with Bollywood, but also Hollywood, Kolkata's Tollywood and Urdu-language films from West Pakistan, the local industry was producing far better films. Clearly protectionism is not helping the industry to survive. Also not helping is the fact that there is little profit incentive in the first place for these so-called commercial films, as they are largely made with black money seeking to be white, using a corrupt “credit” system that rarely gets repaid.

|

| Prito Reza |

Let's take a moment to consider the independent production sector, outside of FDC. The more recent rise in these films, produced by television or otherwise, has been a positive trend. These films can hardly benefit from the credit-based services of FDC, since they are largely made outside that system by more quality-conscious filmmakers. Costs are therefore higher, particularly since laboratory services must be sought outside the country. The profit incentive is therefore also stronger, but unfortunately, there is little chance of profit given the limitations of the exhibition sector, as I outline below. Most releases are only done in a handful of halls, and then immediately given a television “premiere”, to ensure a quick return. However, with this kind of release, there is a natural budget barrier for any producer who is concerned with getting a return on their investment. Filmmakers who go for higher budgets are either half-mad or have financing in the form of grants or black money that make the investment worthwhile. The only other way to circumvent this “budget barrier” is to go for a parallel release outside the mainstream cinema hall system. This is our experience with Muktir Gaan, and more recently Runway. In this scenario, producers become their own distributors and exhibitors, printing their own posters, tickets, and banners, publicising through the newspapers and television as well as through online networks like Facebook, hiring alternative halls and projection equipment, travelling around the country and running the shows directly themselves. The chance to directly interact with one's audience is an incredibly rewarding experience, and certainly the returns are potentially much higher, but it is also incredibly exhausting and time-consuming for filmmakers who could be expending their energies on their next film.

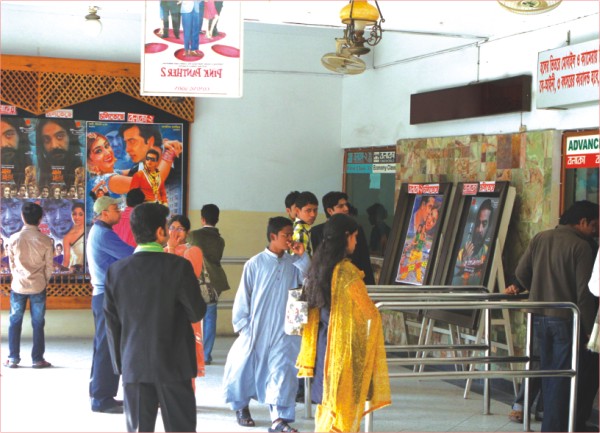

On the exhibition side of the industry, the situation is equally, if not more dire. Out of the approximately 1,500 cinema halls that were in existence at the time of Liberation, only 500-600 remain. Most of these are in a terribly dilapidated condition, with tin roofs, wooden benches and mud floors. The projectors, locally made, leave costly film prints in shreds after a week of projection. Screens, usually made of painted jute or cheap white cloth, are caked with decades of dirt and grime. The light from the projectors is so weak that the image on the dirty screen is no more than a dim shadow. The sound, already poor quality due to the FDC dubbing, is so distorted in the hall sound system that human voices sound like crows. The 70-80 halls that are slightly better are only marginally so, with chairs instead of benches and concrete walls and ceilings. Out of these 20-30 are of a minimum middle class standard, and of these again there are only a handful that have high quality projection and air conditioning. Contrary to the global trend of 'multiplexes' -- modern halls equipped with two or more screens catering to middle class audiences -- Dhaka to date has only one multiplex theatre. Huge areas of the city, well-heeled areas such as Gulshan, Banani, Uttara and Dhanmondi, have no cinema halls at all. It's no wonder that the middle class, once the backbone of the audience, has long since deserted the theatres.

It is important to note here that cinema halls are the front end of the industry, the stores where our goods are sold. The collapse of the halls would immediately backward link to generate the total collapse of the production and distribution sectors. The halls are the industry's most important physical asset. It is the part of the industry that directly concerns the people as well as the government. To save the industry the cinema halls need to be saved: they are the immovable infrastructure of the industry.

|

Prito Reza |

Right now, halls are closing down on almost a weekly basis around the country. During our country-wide release of Runway, we had direct exposure to this reality, Since December of last year, Tareque extensively documented the closure or impending closure of dozens of halls in different districts. In interviews with hall owners, employees and audience members, a clear picture began to emerge that reinforced what we already knew theoretically. If one were to place the blame merely on the poor quality and low quantity of films being generated on the production side, inside or outside of FDC, that would only be part of the explanation. There are other, essentially structural issues that have doomed the halls to oblivion. An exorbitant ticket tax of 150%, dating back to the British period, has been the first barrier to growth in the exhibition sector. Despite an attempt to revive the industry by reducing this tax in the late 1990's from 150% to 100%, it remains one of the highest cinema taxation rates in the world. Consequently there is little left from the sale of tickets to go back to the halls for reinvestment, or to the producers and distributors to cover their expenses, not to mention generate a profit. Furthermore, halls outside of Dhaka are forced to pay distributors an advance “minimum guarantee” or MG, a flat rental fee for any film they want to run. The producers and distributors logic for the MG is that ticket sales are too difficult to track due to complicated and corrupt accounting practices. But the MG system further depresses the sector, and discourages smaller halls from taking better films with higher rentals in favour of the lowest quality cheaper ones. Meanwhile, due to a policy dating back to the 1965 Indo-Pakistan War, Indian films are not allowed to run in Bangladeshi halls. Although originally motivated on political grounds, after 1971 the so-called economic logic of protecting the local industry has meant that the practice has persisted until today. No doubt noble in intention, this policy is ultimately destructive in that Hindi films are everywhere anyway, whether on DVDs, satellite channels, computers or even cell phones. Next to any cinema hall you will find a CD shop where all the big hits of Hindi cinema can be bought for the price of a hall ticket. Not only are cinema halls being deprived of potential block busters that could allow them to revive and reinvest, the government is being deprived of huge revenue. If there were an adequate supply of good local films to ensure the survival of the cinema halls, this would of course not be such an issue; however, as we've already seen, this is hardly the case.

Now, you may ask, why should we care? If the films are so bad anyway, if FDC is collapsing along with the cinema halls, if independent films are a doomed enterprise, what does it matter? Perhaps we should let it die, and just move on to making films with our digital cameras and cell phones, uploading them on You Tube. But there is a bigger picture here to consider. Firstly, the fact remains that despite its shortcomings, the film industry provides a livelihood for millions of people, both directly employed in the production and exhibition sectors, and indirectly employed in related businesses such as the thousands of small businesses that thrive next to cinema halls. In a country of Bangladesh's population, with a still considerable film-related infrastructure, it is a potentially huge economic sector. Secondly, in any country, and Bangladesh more than many, film provides essential entertainment for an otherwise entertainment-deprived people, particularly outside the capital and in economically depressed regions. But film is not merely important for its entertainment value: film also contributes to social and political stability by giving people, particularly frustrated youth, an outlet for spending leisure time, away from political agitation, drugs, eve-teasing and other anti-social activities. It is interesting to note here that after the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, it was the Iranian Government that took the initiative to build an additional 500 cinema halls around the country, in the interest of ensuring greater stability. Film also has a far-reaching significance in the society at large: when cinema culture is healthy and family-centred, it can provide a means of preserving and sustaining cultural traditions, positive societal values and national identity. One wonders the role that Bollywood cinema has played over the decades in forging a sense of national identity in an otherwise factionalised society like India's, with innumerable distinct local languages, ethnic origins and traditions. We should also be reminded that the powerful medium of film can be an effective vehicle for positive social change in a society, exposing injustice, encouraging tolerance, and celebrating diversity. And last but not least, cinema can potentially provide huge revenue streams for the government once it is properly revived.

But how to revive the industry, when it is already almost dead? Even if we all agreed that it needed to be revived, where would we get the economic planning and know how to do so? Interestingly enough, there are many precedents in the region that can serve as models. In fact, Bangladesh lags behind as the ONLY country in South Asia that has not initiated major reforms in the industry in recent times. Let's start with our biggest neighbour, India. Up until 10 years ago, the entertainment tax was 150% of the ticket cost in many states, again a legacy of the British era when theatre and cinema were considered to be best relegated to an elite pastime. Complicated licensing laws for cinemas dating back to 1918 made it a lengthy and costly process to establish new halls, much like the current situation in Bangladesh. Films were financed mainly by mafia or other black money sources, with poor returns to producers and distributors due to disorganised, corrupt and difficult-to-track accounting practices, again a familiar scenario. Given this situation, from the 1980s onwards, cinema halls around the country were losing business and closing down. Occasional “hits” would lead to temporary upswings and some hall renovations, only to be followed by long stretches of dismal business.

This all changed in 2001. Due to increasing pressure from various stakeholders, film was given official industry status by the government, thus entitling film-related enterprises and establishments to special tax breaks and simplified bureaucratic procedures, and making the industry an attractive investment for banks and corporate entities. Mafia and black money began to retreat. In addition, the Indian government, recognising the critical role of cinema halls in reviving the industry, introduced a 4-5 year “tax holiday” (tax exempt status) for entrepreneurs to establish new multiplexes. Other tax incentives, such as reduced utilities and land taxes, were also introduced. Overall, there was a reduction in the ticket tax to an average of 30-45%, even less in some states such as Tamil Nadu, at 15%. At the state level, special policies were introduced to promote regional language films, such as in West Bengal, where Hindi films are heavily taxed to subsidise the local industry, while local films are barely taxed at all.

Within a few years, dramatic results began to be seen. Firstly, there was a dramatic growth in multiplexes throughout the country, targeting young, urban, upwardly mobile audiences.

By 2010 there were over 700 muliplex screens nationwide. Though only accounting for roughly 5% of India's 13,000 screens, they brought in 30-35% of the total box office sales. Multiplexes also ushered in a shift to new, digital forms of projection (the high-end version, closest to cinema quality, is 2K). This reduced print costs for producers and distributors, and enabled simultaneous release over many more theatres, thus reducing piracy. Electronic ticketing, a Multiplex hallmark, also simplified the accounting process and ensured proper returns. The Muliplex format, with its more sophisticated audiences and better returns, also encouraged higher quality, better-scripted films, and more experimentation with styles and genres. “Multiplex film” became a marketing category. Multiplexes also drove huge increases in consumer spending through affiliated shopping malls and restaurants. Although not initially given tax concessions, single screen cinemas, catering to more general audiences, were later also offered tax breaks to upgrade facilities or subdivide their theatres into two or more screens. Overall, these policies led to a renaissance of the Indian film industry over the last 10 years, with more and better films being produced for larger audiences and bigger profits. What's more, Multiplex films were also ideal fare for the economically powerful legions of Indians settled abroad, and foreign sales of Indian films become an increasingly important source of revenue.

But India was not the only country initiating reforms. Pakistan's industry, which had seen its Golden Age of Cinema in the 1960s and 70s, was in a total state of collapse at the turn of the millennium. In 1990 there had been 750 theatres around the country; in 2002 the number had shrunk to 175. In the late 1990s an attempt was made to salvage the industry by reducing the entertainment ticket tax from 150% to 65%. Tax incentives were introduced to encourage multiplexes, and in 2002 the first multiplex opened in Karachi, with a dozen more quickly following. In 2004, cinema halls were completely exempted from paying any entertainment tax until 2009, and this policy has been extended in many states including Punjab. Most remarkably, in 2008, the decades-old ban on Indian films, also dating from 1965, was completely withdrawn. The same year the Pakistani hit film Khude Ki Liya was released widely throughout India on over 100 screens.

In Sri Lanka in 2007 a series of major reforms were proposed in the 2007 budget. The primary reform was a tax holiday of 10 years for newly constructed cinema halls using modern equipment approved according to prescribed guidelines. In addition, a 5-year tax holiday was granted for existing cinemas that upgraded their facilities along the same guidelines. To give further incentives, a package of tax reductions and exemptions was introduced at the production, distribution and exhibition levels for such things as laboratory charges, import of equipment, utilities costs and other services. To ensure the financial stability of the industry, higher taxes were levied not only on imported films, but also on imported tele-dramas and advertisements. The revenue from these taxes is being used for reinvestment in the local industry, including a new Film City and Training Institute. Even Nepal, with its tiny local industry, has also introduced reforms, including incentives for new multiplexes with digital projection technology, and a two-tier taxation rate, with Hindi and other foreign films taxed at 25% while local films are only taxed at 13%. Kathmandu, with a population of less than one million (as compared to Dhaka's staggering 15 million), already has eight modern multiplexes, with another 19 new halls under construction.

So, it seems the road to reform is not so distant after all, with so many successful models near at hand to follow. The formula is fairly straightforward: revive the film industry by targeting the exhibition sector. Introduce a package of tax incentives and reforms to promote the growth of new modern cinema halls and upgrading of old facilities. Introduce more competition, but tax foreign films heavily and reduce the local entertainment tax to subsidise reinvestment in the sector. More specifically, a package of proposals for reform of the cinema hall sector could be as follows:

1. Tax holiday of at least five years for new multiplexes with modern equipment, facilities and ticketing system.

2. Tax holiday of at least three years for renovation of existing halls (must include specified upgrades of projection & sound equip, and facilities improvement)

3. Specially reduced land/facilities/electricity tax rates for cinema halls to encourage preservation of existing halls and establishment of new ones.

4. Promotion of introduction of digital projection (should be specified as 2K) and surround-sound. This should follow the standard international configuration for digital theatres.

5. Facilitate controlled importation of foreign films, with high taxation rate to subsidise a low tax policy for local films. Initiate a bilateral policy agreement for Indo-Bangladesh film exchange.

6. Tax concessions on import of projection and sound system equipment

7. Simplification of licensing and permits for new halls to speed establishment. Additional incentives for halls outside Dhaka metro area to encourage cinema hall networks in smaller cities and towns.

8. Reduction in the overall ceiling for the entertainment ticket tax with a two-tier system to promote national cinema (i.e. 10% for local films, 50% for foreign films).

9. The reduction in the tax burden should be reflected in fixed reduction in ticket prices to give added audience incentive. Also fix increased percentages to be allotted for Exhibitors as well as for Producers and Distributors on a fair and equitable basis.

As in other countries in the region, these reforms should have a positive impact on the entire industry through backward linkage to the distribution and production sectors. Film producers, long starved of proper venues to show their films, will invest more money in more films to meet the demands of a growing, more middle-class audience. Distribution companies will also be revived to meet the demands of producers who need intermediaries to market and disseminate their productions. And filmmakers will be inspired to make better films with better budgets. But it is just a beginningthere are so many reforms that will remain, of the functioning and role of FDC, of the Censor Board, and of the film-related government bureaucracy. Of course, the real start, is to begin to dream, and to share our dreams with the public, so that together we can move forward towards a revitalised film industry in Bangladesh.

Catherine Masud is an American-born film maker based in Dhaka.