Inside

|

Inconvenient Truths about Bangladeshi Politics

The country may be heading backwards towards

confrontational politics yet again, warns ALI RIAZ.

|

|

Bangladeshi politics is on a confrontational course, once again. The statement by the Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina at a news conference in New York on September 25, 2011 dismissing any possibility of future negotiations with the opposition -- calling them “thieves and cheats”, and a response from the leader of the opposition Khaleda Zia within 48 hours at a public gathering in Dhaka that “all doors are [now] shut for peaceful transfer of power” finally made it

official. It is not that there was ever a doubt that these two leaders would again lock horns, but such definitive statements from both parties underscored the return to conflictual politics. In the past year the question was often posed whether the country would be “back to square one”; in recent months media pundits have concluded that it is indeed “back to square one” and the question now being faced is how far the country is likely to regress?

A solution without solving the problem

The high hopes of establishing a transparent and accountable democratic system of governance after the popular uprising in 1990 faded in less than two years and agitational politics returned by late 1995 leading to a chaotic political situation in 1996. The uprising of 1990 was not made in a day but was a result of many deaths and untold sufferings over almost seven years. Similarly, the 1995-96 episode cost lives and caused misery to many. Once again, the ordinary citizens, who suffered most in these disruptions, and the analysts expected that politicians would have learned their lessons and chart a new course. The country muddled through the following decade; but only muddled through, and there were very few things in the political arena to be optimistic about.

Only a few dissenting voices asked what prompted the crisis and what guarantees that it would not return. The underlying causes of the crisis were never dealt with. In the absence of soul-searching and a robust debate two schools of thought emerged. “The problem has been solved” school adopted a very complacent tone; it was all about holding fair elections, and the constitutional provision -- the non-partisan caretaker government -- had ensured fair elections for eternity and therefore all would be well henceforth. The other school's approach was almost Harry Potteresque -- “he who cannot be named” can do no harm if you do not say the name. Thus avoid the “inconvenient truth” and all will be well. Both approaches led the nation down a blind alley. The crisis reappeared in 2006, or one can say the inevitable happened in the sense that as no one tried to change the course of the downward spiral, the nation reached rock bottom. But a political crisis is not a natural disaster that can appear at very short notice. If and when it is described as whirlwind, this is to describe its degree not its genealogy. Such a narrative makes the crisis comprehensible. Even for natural calamities, there are ways to prepare and most communities have some kind of contingency measures in place.

|

|

The misplaced optimism and a warning

Interestingly, in the summer of 2006, well before in the dramatic events that would be unleashed in October, some levelheaded people did anticipate a crisis of some kind. But they were assured by pundits and most political operatives that there were no reasons to be pessimistic. Private conversations with political leaders in December 2005 and January 2006, during a trip to Dhaka, gave me the impression that a brinkmanship attitude had taken hold among leaders and that possible options were becoming increasingly limited. In February 2006 my impression was reinforced after I met a group of Bangladeshi civil society activists, lawyers, journalists and policymakers at a meeting. When I returned to Dhaka in summer 2006, pundits and politicians advised me not to worry; I, however, remained unconvinced. I penned a commentary, entitled “The Crippled Caretaker” (Himal Southasia, August 2006) where I described the mood: “Some analysts dismiss the concerns, saying that political crisis is nothing new in Bangladesh, and that in the end a solution is always found. Such a fatalist attitude is based on viewing the present situation as reminiscent of previous 'crises' -- the last days of the military regime of General Hussain Mohammed Ershad in 1990, or the political crisis during the Khaleda Zia regime of November 1995-March 1996, both of which were resolved peacefully. On the surface, the argument is simple and forceful: however difficult it may appear, or however self-centred the political leadership may be, the Bangladeshi elites have a stake in the current system and will find a way to keep it running.” The then ruling coalition -- the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Jaamat-i-Islami (JI), and the opposition parties led by the Awami League faced each other, waiting for the other to blink. The rational argument was that one party would blink, especially with the stakes being so high; or alternatively, both would agree that it was a no-win situation. This optimism did not come to pass, neither party blinked.

By August 2006 it was evident to many, as I summarised: “there are serious doubts as to whether the exercise [election] will be held on time -- and if so, whether it can be fair, and with participation by all political parties” -- a fair and timely election [i.e, January 2007] was almost impossible at that time. The shadow of the military began to loom large. In a humble way I tried to draw attention to an untoward situation: “Missing in this perspective is the presence of forces -- international, regional and domestic -- with agendas detrimental to the national interests of Bangladesh. It does not take an alarmist to underscore the possibility that, with the overall governance in disrepair and a badly organised general election, the country may be dragged into a situation that could demonstrate the weaknesses of multi-party representative democracy. The inability of leading political forces to resolve the crisis would then benefit a small but lethal force.” Unfortunately, the events of January 2007 leading to two years of military-backed non-partisan technocratic regime bear out my prediction.

The reason for reprising this five year old commentary is simply to make a few points, which are not new at all, but worth recalling: that there are always telltale signs of a political crisis and its consequences, that a political crisis does not have one single trajectory -- it can be steered in a different direction if the political actors are willing to but sans serious efforts it will reach a destination whether one likes it or not; and that avoiding an 'inconvenient truth' does not make it go away -- 'he who cannot be named' does harm even if you don't name him. As the country is heading for another round of the same old crisis, signs of brinkmanship, of intransigent attitudes of all parties concerned, and of utter disregard for the misery of the people is now becoming obvious. It is therefore pertinent to examine what trajectory it might take and how it can be avoided.

|

|

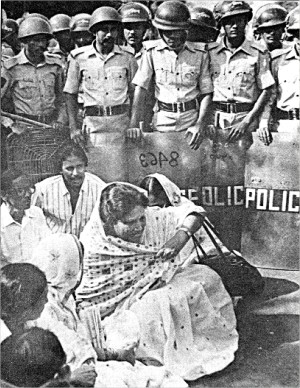

Star Photo |

The current imbroglio

The statements of the two leaders of the country, who have ruled alternately for the past two decades, suffice as indications of the impending impasse. But the situation has been brewing for quite some time, perhaps from the day after the election. The BNP never accepted the election results of 2008 at heart -- it never attempted to understand the causes of the worst possible showing ever for the party let alone admit that it was their wrong doing that made the nation suffer. The JI correctly understood that the popular mandate to the AL was at least partially based on the promise that the AL would try the war criminals of 1971 if voted to power; but the JI did not want to admit the fault and accept the consequences. The AL, on the other hand, misjudged the results as a “license to rule” instead of a “mandate to govern”. In fact, politicians of all shades have failed to differentiate between these two since the independence of the country. Misgovernance followed -- proof of the ruling party's arrogance and total disregard for the rule of the law can be found via a quick perusal of any Bangladeshi newspaper. The reader will find evidence of the blanket impunity accorded to party activists, the condoning of mob justice, extrajudicial killings and mysterious disappearance of citizens. The furious reactions of the ruling party leaders including the Prime Minister to any dissent -- inside or outside the parliament, small or big, even on legitimate issues -- sends a chilling message

Parliament: Nobody's there?

The parliament has become one of the most dysfunctional institutions of the country. A report by a parliamentary watchdog published in June 2011 noted that the percentage of boycott of sessions was 34 in the fifth parliament (19911996), 43 in the seventh parliament (19962001), 60 in the eighth parliament (20012006) and 74 in the first two years of the existing ninth parliament. In all instances, the opposition evidently feels that it is not accountable to anybody and does not owe anyone an explanation for being absent. Ruling party members have the same mindset. Otherwise how can one explain the frequent quorum crisis that delayed the sittings when the ruling party alone has two-thirds majority and the ruling coalition has three-fourths of parliament members? On an average, each sitting was delayed by 39 minutes according to the report of the watchdog. In six sessions of the ninth parliament, Tk 19 crore was wasted just in waiting for the lawmakers to turn up.

Constitution after the amendment

The 15th Amendment of the Constitution, passed by the parliament in June 2011, has provided the opposition with a legitimate excuse. The amendment, among other things, eliminated the proviso for the caretaker government (CTG) from the constitution. Indeed a lame excuse is used by the government -- the highest court declared it “unconstitutional”. But the fact remains that the complete verdict of the court is still pending and that the court ruling had also observed that the next two elections may be held under the CTG. These changes are made in the parliament in the absence of the opposition. Opposition was not interested in participating in the process of the amendment arguing that it is futile because the decision about the changes had already been made. It was true. But opposition did not participate perhaps because it was difficult to argue for a case which it previously opposed and insisted unconstitutional. The amendment has other disturbing aspects; importantly, insertion of a clause that makes any criticism of the constitution an offence punishable “with the highest punishment”, and 55 clauses are now deemed “basic provisions” which are not amendable. Interestingly the opposition has made no objection to these severe amendments. The post 15th amendment Bangladesh constitution has become a mishmash of contradictory statements in regard to the role of religion -- on the one hand, Islam is the state religion (a provision that is now non-amendable in future) while on the other hand, the constitution asserts that the state will not grant political status in favour of any religion, Juxtaposed with the basic principles which include secularism, one gets a picture of the constitution's internal contradictions.

An election: To be or not to be?

The opposition leader has declared that her party and allies will allow no general election without the caretaker government system reinstated. She stated unequivocally that, “A caretaker government and a neutral election commission are a must for acceptable polls. In the absence of those, we won't take part in the election.” The choice of words of Khaleda Zia is reminiscent of 1996 when the BNP tried to get away with a fraudulent one-party election under a partisan election commission. The BNP failed, thanks to the AL; but in the eyes of the BNP it is time to pay back the AL in its own coin. Both parties seem to have learned the wrong lessons from the 1996 February election episode -- a blemish on the electoral history of the nation since 1991. For the Awami League the lesson is how to create a facade of participation of opposition, while for the BNP it is a matter of vengeance. The air in Dhaka is thick with rumour that if the BNP does not join the next election, the Jatiya Party led by former dictator General Ershad, currently a coalition partner, will contest alone. Ershad has sent similar signals. Some of the AL leaders are happy that a loyal opposition is ready to provide legitimacy to the election.

It is also worth noting that Khaleda Zia's conditions for the BNP's participation in the next election include “a neutral election commission” (EC). The present members of the EC were appointed by the caretaker government in early 2007 after forcing out the most controversial members of the EC appointed by the BNP regime. Save some faux pas during the caretaker government (2007-8), the EC has done a reasonably well job thus far. The terms of all the three members will end by April 2012. Will the AL follow the BNP in appointing partisans as EC members? Judging by the actions of the AL during the past two and a half years, there is no reason to think otherwise. While removing the caretaker provision from the constitution the ruling party leaders including the PM said that the EC will be strengthened. No such steps have been taken. All of the requests from the EC to provide more resources and autonomy have fallen on deaf ears. The constitution stipulates that the EC members be appointed by the President under rules set by the parliament. The rules for appointment have never been formulated; thus the President can appoint anyone he chooses. The PM has indicated that the government is ready to reconstitute the EC through dialogues, but only time will tell whether that is a sincere offer.

Return of a ritual

As the election commission issue came to fore and the threat of the BNP to boycott the election began to loom large, a ritual of Bangladeshi politics has also returned: calling the two leaders to discuss, make compromises and build consensus. Members of the civil society, the business community and a segment of political activists have been chanting this mantra for two decades to no avail. Hoping that persistence will pay off, they are saying it again. The media, particularly those with no partisan affiliation feel it is their moral responsibility to underscore the need and reiterate the call. But they too perhaps know it is wishful thinking. The zero-sum game subscribed to by the two major parties and their supreme leaders Sheikh Hasina and Khaleda Zia does not provide them with any room to meet in good faith, let alone compromise on any issue. The call based on a moral ground or democratic principles has had no effect for these leaders since 1991, why should they behave differently now? Many people have been arguing over the past 30 months that the experience of the caretaker regime between 2007 and 2008 -- the humiliation and incarceration, whether lawfully or not -- should make them think twice. This line of argument presupposes that the right lessons have been learned.

Lessons learned!

Undoubtedly, the parties have learned something. The PM in oblique reference to the two years' of the CTG repeatedly insists that extra-constitutional government will not be tolerated in future and the 15th amendment is designed to prevent it. The BNP, on the other hand, is still in denial mood -- 'the CTG conspired to defeat the BNP' is the dominant frame of mind. How the crisis emerged in 2006 was never an issue that featured in party discussions. Questions such as how and why corruption engulfed Khaleda Zia's government and the family, and why the line between clandestine organisations and the state blurred creating a serious threat to the nation's security are not something the BNP leadership want to discuss. Lack of such retrospection in the BNP provides the government with the opportunity to contend that the BNP's opposition to the government is merely a ploy to save the corrupt (including Khaleda Zia's two sons), and stop the war crimes trials in their tracks. These allegations are politically motivated, but not entirely unfounded.

The war crimes tribunal

The establishment of the War Crimes Tribunal in March 2010, an electoral commitment of the AL, has put the Bangladesh Jamaat-i-Islami on the back foot. After all, of seven politicians indicted thus far, five are JI leaders. Besides, the JI knows too well that the government has enormous popular support on this issue and the JI cannot mobilise to stop the trial. To do so, it must use other issues to derail the process. Revival of the 4-party alliance after almost two years and Khaleda Zia's description of the trial as “a mockery” in September was the best thing to happen to the JI since the election. The decision of the BNP to maintain its distance with the JI in the past year and to remain ambiguous on the war crimes tribunal were prudent moves, but now it has once again embraced the JI and all its problems. This decision will cost the BNP dearly as its acceptability to a segment of people will decline. But it will cost the nation more if the government fails to try the accused individuals in a manner that meets international standards and is acceptable to the international community. To date, there are concerns within the international community whether a credible and fair tribunal can take place under the present rules of procedure and the political climate. The failure to try the war criminals will have a long-lasting impact as will a show trial. The onus is on the government, but the government's performance to date is not satisfactory.

Quo vadis?

With this survey of the political landscape in front of us, we are faced with the question what is the trajectory of Bangladeshi politics? In the short term the nation does not have an appetite for street agitation and chaos, but neither does it have the patience to bear with the malgovernance for too long.

Five years ago, in the context of the brewing crisis, I was of the opinion that international, regional and domestic forces with agendas detrimental to the national interests of Bangladesh may come into play. It is equally true today and for any major crisis situation for the foreseeable future. In 2006 the international community tried to help Bangladesh avert the crisis; afterward it has taken flak for its initiative. Whether the involvement of foreign diplomatic missions in local politics was a violation of diplomatic norms is an open question. But it appears to me that there will be very little interest in taking initiatives of a similar kind if the nation plunges into another crisis. The experience, of course, is a factor. But more so because of the global situation; unless dramatic changes take place in the hot spots and in the global economy, the global players will remain busy elsewhere. Bangladesh may not feature very high on their list of priorities.

One must also pose the question, with a sense of resignation, how long will the nation remain hostage to these two parties and their obdurate leadership? The question has been asked for quite some time with no answers forthcoming. Some are clinging to the hope that these parties and their leaders will realise the popular aspirations and act on them. We all know, save divine or happenstance intervention, that this is unlikely. As such, the nation should brace itself for another round of confrontation -- the backward journey has now gained momentum, it will be a race from here. But where will it take the country -- 2006, 1996 or further behind? Let us ask the leaders, have they calculated how far behind they want to take the country?

Ali Riaz is Professor and Chair, Politics and Government, Illinois State University.