Inside

|

Quasimodo(s) in the Bell Tower:

An apology to the children

Of Bangladesh

On the occasion of Universal Children's Day (November 19)

SHAHANA SIDDIQUI talks about giving children back the childhood they often lose out on.

Mobassher Choudhury of the band Old School

Prologue to an apology

J.M. Coetzee once said that South African literature is “a literature in bondage” which is “unnaturally preoccupied with power and torsions of power”. This is so because colonialism and its manifestations i.e. apartheid [other forms of occupations] create “deformed and stunted relations among human beings” which in turn creates a “stunted inner life”. No words reflect more the truth to me than these on the condition of the children of Bangladesh.

We flaunt our token “achievements” and “success stories” supported by numbers and figures to masquerade our failures to give especially the poor children of Bangladesh a real future where they can dream, think, live without “bondage” without a constant reminder of their realities. For every one child in school, there are 10 who drop out. For every one child surviving till the age of 10, there are 20 who are not. For every one girl child we are saving from sexual assaults/violence, there are hundreds of schoolgirls who will never come forward, never tell us their stories. And for the thousands of children who are asked of their hopes and aspirations, not one will we help to fulfill their real dreams.

So, on the 20th anniversary of being a proud UNCRC signatory, I offer my much bottled up anguish over the real state of children in Bangladesh. I offer a story that has no fairy god mothers, prince charming to the rescue, or miraculous endings. This is about us -- the politicians, government officers, child rights activists and donors -- the dutybearers -- and our business of childhood loss. This is about how we lock up dreams and hopes in colourful “child-friendly” reports, art exhibitions and socio-economic indicators. This is the story of how we have created an entire generation with stunted imagination and limited opportunities.

We don't need no (substandard) education

This year's State of the World's Children, brought out by UNICEF every year, focuses on adolescents. By the time this article goes to print, we will in fact have 7 billion people in this world where 1.2 billion are within the age group of 10-19. UNESCO states that “an estimated 515 million young aged 15-24 people live on less than two dollars a day” of which the majority are found in Asia. Along with youth, child poverty is a well-documented and researched phenomenon which shows the direct relations between children born into poverty and the high chances of staying in poverty throughout their adulthood (Moore, 2005).

These facts and figures are nothing new but neither were the consequences foreseen -- what do we do with these kids who are growing up so fast and entering jobless, opportunity-less adult realities? Question to ask is that was it ever possible to give these millions of adolescents great futures with substandard formal and non-formal education, compounded by outdated human resource trainings far behind the global market trends and demands?

National education system has long been deteriorating and the curriculum reflects nothing of new pedagogies and discourse. Instead of creating analytical curriculum, we are more concerned about history re-writing according to the political doctrine in power. Whenever challenges in the education system are raised, ready-made answers are (i.) we do not have enough funds and (ii.) include that topic/challenge in the curriculum.

How are we to have enough funding for education when the education budget includes everything from primary-secondary education to adult literacy to public administration's capacity-building programmes? On an average, approximately 98% of the revenue budget allocated for primary education is for salaries and allowances (Al-Samarrai, 2007). If that is so, why are there schools without teachers or why is the level of education so low? Thousands of unaccounted of teachers sign off to receive their monthly payment without ever stepping into the school premises. This is tax payers' money that we have no way of holding anyone accountable for.

In the past, those who entered the education sector were of high educational qualifications. Now, the last of the occupational option is to teach at schools. The low-salary, the inadequate trainings are merely excuses to keep the job. No one can train anyone to stop educators from hitting children or not showing up to class at all.

These are basic sense and decency. When there is finally a “discovery” by educators on “joyful learning” it shows just how awful the state of education is -- learning should be innately joyful, or else it isn't learning -- it is turning kids into talking parrots.

On the other side, a large portion of the development expenditures in both primary and secondary education are spent on building new schools. There is a need for more school buildings but what good is a school without teachers, a school without educational equipment and books?

Textbooks that are either too late or printed on paper worse than toilet paper -- are the magic bullet solution to every national challenge from sexual harassment to climate change! Every child-related development challenge is to be included in the textbooks. Why is the onus of ensuring children their rights on the children themselves? I always quote a wise old headmaster I once met in Jamalpur -- “our children are overburdened with subjects and have no time to enjoy learning”.

The great champions of education in the non-profit sector are no better than their government counterparts. In the name of education for all and achieving MDG 2 (universal education), non-profit educationalists made it their life crusade to set up non-formal education schools and centres which in my personal opinion is one of the main factors that destroyed the national education sector. Non-profit/non-government schools were supposed to be the buffer between government schools scaling up and current demand for education centres -- they were never to become a “system”, a “sector” of their own. Instead we now have different streams of education where some schools are formal with informal approach, while others are non-formal with formal recognitions; and then there are those which are informal with non-formal curriculum!

Instead of streamlining education, enforcing substantial changes in the ways the State is providing educational services, the non-profit sector has created a patchwork of fragmented approaches and methodologies. It is always easier to experiment on other's children, especially on goriber baccha but never on our own.

Death by hygiene

A dear friend also working on urban poverty observed the development sector's obsession with health and sanitation of the poor, especially the urban poor. “Shahana, amra mone hoy water and sanitation diye oder'ke mere phelbo!” Laughable but there is something telling about this statement.

Access to clean water and hygienic sanitation are perhaps the two most important resources to lead dignified lives. Several health issues are immediately prevented for those who have access to these scarce resources. We are all aware of the direct correlation between ill-health and plummeting into poverty. While we know this correlation so well, we provide uncoordinated services where there is training on cleanliness but no clean water, or there is water but no way of keeping one's environment clean.

I worked mainly with urban poor children, visited and evaluated several non-profit schools situated inside the bazaars and slums. I understand and to a certain extent, endorse the philosophy of taking education to the children, but that does not mean classroom spaces need to be next to the truck stop of the bazaar or the dumpster of the slum. Ironic moment no. infinity was when I was evaluating a well-known organisation's informal-non-formal life-skill training class session with the teacher showing the children how to wash their hands and boil their drinking water while we were all sitting next to a mosquito infested pool of three days-old rain water.

What we, the hygienic class of people take for granted is that staying hygienic is not just about “awareness” and “training” -- it is a lifestyle. This lifestyle requires a clean bathroom, access to soap and water, clean clothes, a clean place to stay and a general clean environment. We provide children with these flip charts with pictures but not the real bathroom, or soap or clean water. In a slum where there are turf wars over city corporation's water lines, what is the exact purpose of getting thousands of children to wash their hands at school, a place where they spend only three hours out of their entire day?

Critics will turn around and ask me -- so what do we do, not teach the children how to be clean and hygienic? No. It is easier to provide “soft development” through “awareness-building” trainings. The outreach can easily be counted and looks great in reports. But try setting up just four latrines for every 100 people in any large slum in any of the cities and see what kind of obstacles one faces starting from city corporations authorities to the slum mastaans.

Every day adolescent girls and women in slums and other low-cost, congested housing are victims of sexual assault and harassment, directly because of shared latrines and no space for privacy. These are unaccounted for. During floods, in both urban and rural areas girl children/women suffer tremendously because they are unable to find a safe and private place to defecate. But yes, we will teach poor children how to clean themselves, send out government SMS-es on “shoucho koranor porey shaban diye haat bhalo kore dhuay neen” without giving them the means to sustain that hygienic lifestyle!

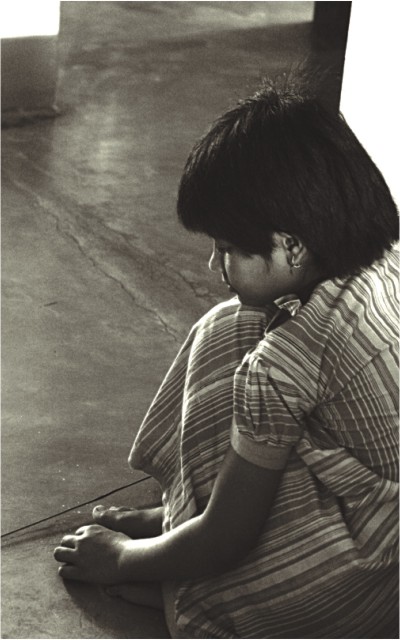

Work to live

A recent joint report by UNICEF, ILO and World Bank, “Understanding Children's Labour in Bangladesh” states that there are 5.1 million working children in Bangladesh. I am not shocked -- are you? With all the timebound programmes we are unable to stop the tap that keeps flowing in the little people workforce. Instead of turning off that leaking tap, we make it “safer” and “easier” for poor people's children to work.

But why should any child work? Why is it their responsibility to earn their living, to finance their own upbringing? Why is it their fault that they live? Why is it that children of age seven or eight are seeking jobs to take care of their families? My instinctive question always has been -- why feed the parents who exercised no responsibility in bringing so many children to the world without the means to take care of them?

Many will argue that everyone, rich or poor, has the right to procreate. Yes, but not at the expense of others. Families are children's first place of safety and belonging. If families are unable to give children a happy, healthy life, familial structures and bonds need to be re-evaluated and revisited. We engage parents in conversations of child rights, but always in a peripheral manner. The main provider for these millions of children is always the State. Why? State is secondary care provider after family, yet there are no concrete family planning and/or family rearing programmes attached to child rights interventions. We will engage with employers of working children on how to be “benevolent and child-friendly employers” but not ask who is responsible for the children to be in this place to begin with. First time, apa bujhi nai, second time, apa ami chai nai, hoyya gese, third time, apa ki aar korum, Allahay dise, fourth, fifth times what excuses are left? It is almost a taboo to talk about holding parents accountable for giving birth without a life. Child labour will never stop if families do not come out of the mindset that children are cash cows.

There are times when I think that perhaps we have no real intentions of ever stopping this continuous workforce of easily malleable and controllable workforce. The substandard education system I have already spoken in length about is not a better option for these children. Let's admit it, the education we provide to goriber shontan is not for them to become doctors, barristers, physicists but rather to be semi-skilled blue collar workers. Why is it that suddenly adolescent is “an age of opportunity” if not to be nurtured with child-friendly terms to turn them into reserved army of labour to keep the economy going? The equation therefore goes something like this:

Poor children, 7-14 = family's cash cow

Poor adolescents, 13-19 = economy's cash cow

Hence, to be born poor = cash cow.

Rights of the child, respect for the child

While 2011 is the year for the youth/adolescents, it was also ironically an awful year for the young. We mourned the deaths of 45 schoolboys in an unbelievable road accident, witnessed the murder of little Hena in the name of religion and community and watched in horror the story of an educator sexually assaulting his student. Incidents like these enrage us, excite us, make us take to the streets and update our statuses on social media platforms. To stop this violence, this pain, we declare we must teach our children their rights. So we “strengthen” our rights trainings and include more topics in their text books. But the language of rights can go only that far, especially for a group of people who are by legal definition, dependents, and not yet full citizens.

The grown up world forgets that children cannot represent themselves in formal institutions, they need adults to advocate on behalf of them. They cannot file a case against violence or vote for their representatives. They can be made aware of their rights but what are rights without having the ability to exercise them?

I look at my own child and ask if I will ever teach him of rights. No, because I will always teach him of respect. I will teach him to respect all that is around him so that all that everyone around him will learn to respect him. Children should not be screaming in front of ministers and government officials on what are their basic rights to live. The point of international charters is to make the adult world responsible towards our young ones, not to create child activists to remind us of our duties.

Instead, in the name of child-rights-approach and child-inclusive-approach and other approaches after approach (!), we have created a tide of child rights activists who are doing our jobs -- they hold meetings with other children, organise seminars, write reports, present in front of officials both nationally and globally and pose for pictures as testament to our programmatic impacts. Once 18, we no longer know what to do with them, we no longer have any need for them. Turning 18 is a lot like an expiration date: Sorry, you are no longer our beneficiary group and what happens to you from this point onward is no concern of ours. Thanks for all the hard work and hopefully all the trainings we gave you on child rights will get you a job somewhere. Oh wait, sorry, we are unable to hire you at our institution although you have worked with us since age 10 because you do not have a foreign post-graduate degree. But good luck with your endeavours.

Few child rights practitioners continue to support these once glorified child activists but these are personal initiatives. We have yet to find an effective transitional phase for youth to adulthood that will ensure them with a sustainable livelihood, a life after all the child rights trainings and seminars.

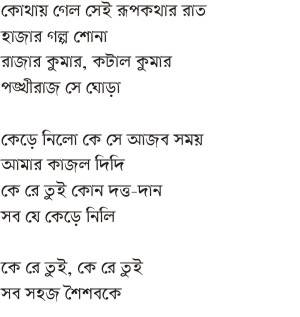

But what makes me sad about the ways in which we work on child rights, is that by engaging children on rights, we speed up their growing up process. To talk of rights, is to talk of duties and responsibilities, is to learn the ways of the adult world. Yes, poor children's realities take away their childhood early on, but must we catalysis that process? Is it not our job to get back some of that childhood? How will we do that when we are taking them from one seminar to another to talk about better schools and playgrounds which they will never see during their tenure at school?

Truth is, we use them, in our pictures, reports, documentary films, career building, research writing and even establishing our own image as people-loving civil society forward thinkers. Just about every international development worker will have a picture of poor children from their field visits on their personal blogs or Facebook albums -- I came, I played, I took pictures, I wrote reports, I did development. No one ever remembers those willing and ready to please smiling little faces but then again they all look the same and there are too many them -- it isn't possible to remember them all, but yes, they changed yours and my lives forever. In many ways, we use these children as our rite de passage to development.

So what do I personally hope for “our future”? I cannot tell you, as adults on the choices you make, but I can urge you to stop and think if you will practise and preach the same rights rhetoric to your own children as you do to other's/poor people's children? Is it only about surviving realities or is it about giving them back their innocence? At our 20th year of relationship with UNCRC, can we start taking its spirit -- the essence which is for children to be children and not some “agents of change” or “child activists” or some ridiculous jargon like that? Can we view the children we work with/for as our own and not a beneficiary group, a stepping stone? Can we stop raising Quasimodos, showcased in high towers and let our children be … children?

References:

Coetzee, J.M. Doubling the Point: Essays and Interviews, ed. by David Attwell, President and Fellows of Harvard College, 1992

The State of the World's Children 2011: Adolescence An Age of Opportunity, UNICEF 2011

Moore, K., “Thinking about youth poverty through the lenses of chronic poverty, life-course poverty and intergenerational poverty”, July 2005, CPRC Working Paper 57, School of Environment and Development, University of Manchester

Al-Samarrai, S., “Financing Basic Education in Bangladesh, Create Pathways to Access”, Research Monograph No. 12, June 2007, Center for International Education, University of Sussex.

The Financial Express, October 24, 2011 http://www.thefinancialexpress-bd.com/more.php?news_id=153904 & date=2011-10-24

Shahana Siddiqui started her development career with child rights. She is a member of the Drishtipat Writer's Collective and can be reached at shahana.siddiqui@drishtipat.org.