Inside

Original Forum |

| Causes of RMG unrest -- Refayet Ullah Mirdha |

| Who Pushes the Price up? -- Asjadul Kibria |

| Padma Bridge: Dream vs reality -- Mohammad Abdul Mazid |

Self-financing Padma Bridge -- Nofel Wahid |

| Unaccountability in Private Medical Services -- Mahbuba Zannat |

Medical Waste --- Mushfique Wadud |

Abysmal state of Emergency Medical Services |

On Clinical Negligence -- Eshita Tasmin |

The Population Growth Conundrum -- Ziauddin Chowdhury |

| Rohingyas and the 'Right to Have Rights' -- Bina D' Costa |

| Two-State Solution: Israeli-Palestinian Peace -- Dr Kamal Hossain |

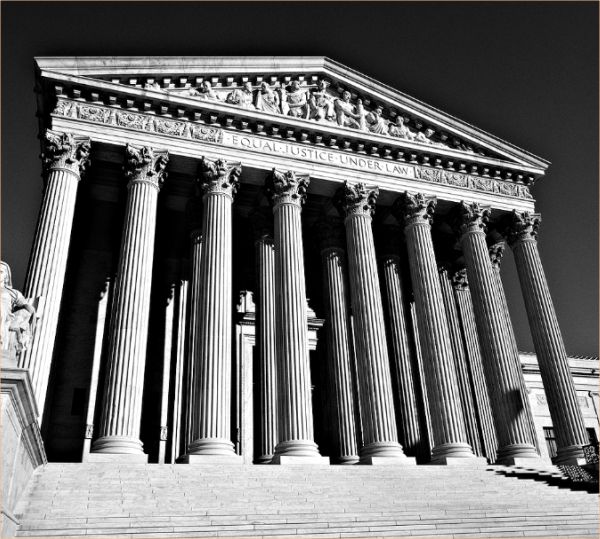

| Forms of Government -- Megasthenes |

A Letter from Alghamdy and War Crimes Trial |

Courtesy

Courtesy

Forms of Government

MEGASTHENES compares different democratic forms of government and seeks to find the hallegenes faced by this system across the globe.

Late in the decade of the 1950s, one of our High School teachers -- an American missionary -- as part of an extra credit work, introduced us to the American system of government. To students of Class 10, the subject was not of great interest; the tutoring though was lucid and compelling, and even years later, when we started to take an informed interest in the issue of governance, a good many of us would remember the basics of what we had been taught. The American constitution is the oldest extant written constitution in the world, and also the most concise. It is geared to the American psyche, and underpins the core values of the country's political culture, namely liberty, self-government, equality, individualism and diversity. The constitution came into force in 1788 and has been amended 27 times. The first 10 amendments constitute the Bill of Rights and were ratified in 1791. Over 220 years back it was the supreme law of the land for 4 million people living in 13 different States; today it applies to over 310 million people in 50 States. Specific powers are vested in the federal government; some powers are prohibited to the federal and State governments; residuary powers are vested in the States. Each of the 50 States has its own state constitution; State law, however, must conform to the federal constitution and federal law. Powers vested in the federal government afforded the basis for a functional polity, sufficient to forge a union of states that would be secure in defence and stable in commerce. Matters wholly within state borders were the exclusive concern of states. There have been changes, of course, over time.

The American constitution provides for separation, and a fine balancing, of powers between the three branches of government; each of which serves as a check on potential abuses of the others. The first article of the constitution relates to the legislature. Some of the Founding Fathers may well have intended that Congress -- the Senate and the House of Representatives -- would be the dominant branch of government. Unlike parliamentarians of Europe, Congressmen are not subject to rigid party discipline. They owe their positions to local or state electorates and not to the national party leadership, and Congress is a collegial rather than a hierarchical body. Its “strength vis-à-vis the executive branch has waxed and waned” at different periods of history; it has, however, “never been a rubber stamp for presidential decisions”. As the US transformed from an agricultural to an industrial society, and then ascended to superpower status, power inevitably tended to gravitate or accrue to the federal government. The federal government has assumed, over the years, greater regulatory and policy responsibilities, and there are today areas of overlap between state and federal jurisdictions, especially in fields such as health, education, welfare, urban development and transportation. The 17 enumerated powers of Congress relate to issues like taxation, currency, immigration, foreign and interstate commerce, declaration of war, and raising armies. Also included is an “elastic clause”; Congress has been conferred the right to make laws that are “necessary and proper” to enforce the constitution. In other words, the federal government can take action “not expressly authorised by the Constitution”, in support of actions that are authorised. The elastic clause has facilitated the growth and evolution of federal authority.

Article II of the constitution pertains to the President in whom the executive authority of the government is vested. The President enforces the laws enacted by Congress, conducts relations with foreign countries, and is the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces; his responsibilities and powers are outlined in the constitution. The US has had its share of strong Presidents, and also those with a limited vision of the office, who were unwilling to compete with Congress for the direction of national policy. In the 19th century, the Whig party posited the view that the President was essentially an administrator to carry out the expressed will of Congress. The 9th President, William Harrison, on assuming office, in fact, pledged to “reverse the despotism that was creeping into the Presidency”. In modern times the Presidency is a much stronger office than could have been envisaged by the Founding Fathers. In the last century, strong Presidents like Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman have established that where vital national interests are involved, the President may employ any and all powers that are not expressly prohibited to him by the constitution. Earlier, the greatest of American Presidents, Abraham Lincoln, had gone even further. At the outset of the Civil War, Lincoln, for strategic reasons, suspended habeas corpus in areas between Philadelphia and Washington DC. At that time Supreme Court Justices served concurrently as Federal Circuit Court judges. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Roger Taney, in his capacity as Circuit Court Judge, ruled that only Congress could suspend habeas corpus if circumstances so warranted; the President's action was thus unconstitutional. Lincoln was unmoved, and ordered the military to ignore writs of habeas corpus issued by Justice Taney. There is some evidence to suggest that he may even have considered placing the octogenarian Chief Justice under arrest.

In the area of foreign affairs the President is perhaps the most powerful man in the world. As the principal architect of foreign policy, he has the power to negotiate “executive agreements” with foreign nations. These have the same legal status as treaties, but, unlike treaties, are not subject to ratification by the Senate. Since World War II, Presidents have negotiated over 10,000 such agreements; in the same period fewer than 1000 treaties have been concluded. A President cannot declare war -- this power is vested in Congress -- but, as Commander-in-Chief, he can send troops abroad for military action. Alexander Hamilton was of the view that the only justification for war by presidential action would be in response to a surprise attack on the country. Jefferson had an even more limited view; any response to an attack by a President, he felt, could only be of a defensive nature, until war was declared by Congress. Since Jefferson's time, Presidents have sent troops abroad for combat more than two hundred times, including in twelve wars, of which only five were declared by Congress. None of America's most recent wars -- Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf wars, Kosovo and Afghanistan -- was declared.

In the domestic sphere there are more constraints on Presidential powers. President Truman, in a letter to his sister in November 1947, wrote in his inimitable manner: “All the President is, is a glorified public relations man who spends his time flattering, kissing and kicking people to get them to do what they are supposed to do anyway”. More recently former President Jimmy Carter, in an interview with Time Magazine, observed that the President's power or ability to “fix the economy” was much less than those of the Federal Reserve and Congress. In messages to Congress, a President can, of course, propose legislation that he believes should be enacted. Much of the legislation passed by Congress is in fact drafted at the initiative of the executive branch. A President has a cabinet to advise and assist him in the discharge of his responsibilities. The constitution does not provide for a cabinet; the system has evolved out of necessity from the time of George Washington. Some Presidents have relied heavily on their cabinets for advice, others less so. Secretary of State Dulles enjoyed the full confidence of Eisenhower. On the other hand, Woodrow Wilson relied more on close confidant Colonel House than on Secretary of State Bryan or his successor Lansing. An important aspect of the Presidency was described by Theodore Roosevelt as “the bully pulpit”; the office of President affords a unique platform to articulate ideas and advocate an agenda.

The British constitution has evolved over time; it is unwritten or uncodified, and based on convention, common law, statute, treaties and judicial decisions. Executive power is exercised by a Cabinet headed by the Prime Minister. In a purely academic or de jure sense, executive authority is vested in the Monarch, and is exercised with the Cabinet's advice. In the past the Prime Minister was merely “the first among equals” in the Cabinet, today he is much more; over time power has gravitated to the office. The Cabinet, comprising some 23 or 24 members, is collectively and severally responsible to Parliament. In Britain, Parliament is sovereign -- primary legislation is outside the purview of judicial review -- but Parliamentarians are not; MPs are subject to a fairly rigid regime of party discipline through the “whipping system”. A periodic circular or whip is issued by party leaders to their MPs requesting them to attend important debates and support the party in Parliamentary divisions. A single-line whip -- underlined once -- is not binding, while a double-line whip is partially binding. A three-line whip, however, may not be ignored with impunity; penalties range from expulsion from the party to lesser punishment. An MP expelled from his party continues to sit in Parliament as an Independent. When the voting strengths of the main parties are close, whips, rather than the quality of debate, determine the outcome.

During World War II, Winston Churchill possibly wielded as much power as any Prime Minister before or after him. In late July 1941, within weeks of the German invasion of the USSR, Presidential emissary, Harry Hopkins, conveyed to Churchill an invitation from President Roosevelt for a meeting. Churchill accepted promptly; he was sure, he told Hopkins, that “the Cabinet would give me leave”. In other words the Prime Minister would need Cabinet approval to leave London for his meeting with the President. On 25 July, Churchill cabled Roosevelt that the Cabinet had “approved my leaving”. Churchill and Roosevelt met in August on board a warship at Placentia Bay, Newfoundland; this was their first ever meeting. An important outcome of the four-day conference at sea was the Atlantic Charter, which outlined the goals of the Allied Powers for the post-War world. At different stages of negotiations, as the Charter took shape, Churchill would keep the War Cabinet apprised of developments and seek its approval. The Charter would inspire a good many international agreements after the War. Churchill recounts all this in his monumental History of the Second World War.

Three powers vested in the Prime Minister -- and in no other Minister -- make for his pre-eminence in the Cabinet. The Prime Minister convenes Cabinet meetings, decides the agenda, and is the last to speak on an agenda item; after speaking, he sums up the discussions. The Prime Minister's summation, unless challenged by another Minister, is the decision of the Cabinet. It should be easy enough to get a sense of the Cabinet's thinking on an issue when out of 23 Members, 5 are on one side and 18 on the other. It is less simple, though, when opinion is closely divided, say 12 on one side and 11 on the other. In such an event, a Prime Minister's summation can even convert a minority opinion -- in which he concurs -- to a Cabinet decision. Harold Wilson, it has been said, would on occasions resort to such a ploy.

While major policy decisions are taken by the Cabinet, individual Ministers enjoy considerable latitude with respect to matters relating to their Departments. In May 1977, the British government appointed Peter Jay, Economics Editor of the Times, as Ambassador to the USA. It was an unusual appointment; in Britain, Ambassadorships are generally filled by career diplomats. Jay was a highly respected journalist, but without experience of diplomacy. At 40, he seemed too young and without obvious credentials for the most coveted of Ambassadorial assignments. Most importantly he happened to be the son-in-law of the Prime Minister, James Callaghan. A few eyebrows were raised; was this nepotism? There was an explanation which addressed this question. The decision to appoint Jay was that of Foreign Secretary, David Owen's, and not the Prime Minister's. Owen, who had been appointed Foreign Secretary only a short time earlier, was a close friend of Jay, and felt that a younger man would be more effective in Washington at that time. Incidentally, Owen, at 39, was the youngest Foreign Secretary of Britain since Anthony Eden in 1935.

Courtesy

Courtesy

From 1973 to 1990, Augusto Pinochet was the head of a murderous military regime in Chile. In 1998, the former dictator went to London for medical treatment; it was an unwise decision. Spanish Judge, Baltasar Garzon, invoking the doctrine of universal jurisdiction, indicted him for crimes against humanity during his years in power, issued an international warrant for his arrest, and sought his extradition to Spain for trial. Pinochet, who claimed immunity as a former head of State, was placed under house arrest in London, while the Courts deliberated as to whether he could be extradited. The case became a cause celebre. Human rights groups favoured his extradition and trial. The Chilean government, on the other hand, wanted him released and allowed to return home, as did former Prime Minister, the redoubtable Margaret Thatcher -- Pinochet had cooperated with Britain during the Falklands war. After a lengthy trial, the House of Lords ruled that Pinochet could be extradited to Spain. Requests for his extradition were also received from France, Belgium and Switzerland. In March 2000, Home Secretary Jack Straw, however, decided that Pinochet was unfit to stand trial. Pinochet was freed, and promptly returned to Chile. To human rights groups it was an appalling decision. Reasons other than solicitude for the old dictator's health may have weighed with Straw. There was a genuine fear that his extradition could precipitate a military coup in his country, and Chile's newly restored democracy could not be put at risk. Pinochet would never travel outside his country again.

The Constitutional Reform Act 2005 introduced a measure of separation of powers in Britain. The House of Lords has ceased to be the highest court of appeal; the Lord Chancellor continues to be a Member of the Cabinet, but no longer concurrently presides over the House of Lords or serves as the head of the judiciary.

The Indian constitution is the longest and most elaborate in the world; it has been amended 97 times in 62 years. It provides for a government that is federal in structure -- but with a discernible unitary bias -- patterned on the Westminster model of parliamentary democracy. As a Dominion under the Indian Independence Act 1947, India, of course, had Westminster style cabinet government even prior to the adoption of the constitution.

In the early years of independence, the Cabinet included stalwarts of the freedom movement, who differed at times on issues with ideological overtones. An eminent Indian diplomat once related an interesting story in this regard. Soon after independence, Maulana Azad placed a somewhat radical proposal to the Cabinet. The “steel frame” of the British Raj, the ICS, was an instrument of colonial rule and had no place in independent India, it should be disbanded. Arch-conservative, Sardar Patel, staunchly opposed Azad. Pandit Nehru agreed with Patel; the ICS represented some of the best talents in India, their experience and expertise should continue to be used. With both the Prime Minister and Deputy Prime Minister opposing it, the proposal was defeated. Azad then came up with a less radical suggestion: perhaps examples could be made of one or two egregious individuals. One name that almost suggested itself in this regard was that of Sir Girija Shanker Bajpai. Sir Girija was of the 1914 batch of the ICS. An individual of high ability and competence, he had, only after 12 or 13 years of service, attained the position of Secretary to the government of British India. He was next appointed Member of the Viceroy's Executive Council, and from 1941 had been serving as Agent General in Washington, a position comparable to an ambassador. As Agent General, a major responsibility of his was to lobby important centres of influence and public opinion in the US, to persuade them that India was not ready for independence, and that the people of India were content with British rule. Sardar Patel concurred; Sir Girija should be retired. Nehru opposed: Sir Girija had served his political masters loyally and well, and should do the same in independent India. Pandit Nehru prevailed, and Girija Shanker Bajpai would be appointed the first Secretary General of the Ministry of External Affairs.

In the early 1950s, President Rajendra Prasad raised a major constitutional issue. The government had decided to effect changes in Hindu personal law through appropriate legislation. The President, who was devout in matters of faith, had reservations in this regard, and wanted to know from the Prime Minister if the Cabinet decision was binding on him. He pointed out that the constitution vested executive power in the President. True there was a Council of Ministers, headed by the Prime Minister, to aid and advise the President. Nowhere, however, was it stipulated that such advice was binding on the President. Nehru assured him that it was, that the language of the constitution had to be interpreted in the context of the norms and conventions of the Westminster model. Nehru suggested that Prasad seek the advice of the Attorney General to allay any doubts. When Attorney General, MC Setalvad, confirmed Nehru's interpretation of the constitution, Rajendra Prasad did not persist. A very distinguished Indian civil servant told me that if the matter had been referred to the courts, the verdict would not have been different.

The Judges would have heard the arguments and also looked at the records of the Constituent Assembly debates. Relevant transcripts would have made clear what the Assembly had intended. In 1976, Mrs Indira Gandhi resolved the issue beyond any question. The 42nd constitutional amendment clarified that the President, “in the exercise of his functions,” would “act in accordance with” the advice of the Cabinet.

The Indian constitution distributes legislative powers between the Union and the States. There are three lists of subject-matters on which laws may be made. The first list enumerates the subjects covered by the federal Parliament, the second relates to subjects under States, while the third is the concurrent list of subjects that fall within the purview both the Union and the States. State law, however, must be compatible with federal law, and during a state of emergency the federal parliament is vested with the power to make laws on matters in the State List. Residuary powers are vested in the federal legislature.

The federal government, under Article 356, can impose President's rule, or direct federal rule, on a State if there is a failure of constitutional machinery in the State. State governments, in such cases, may be suspended or dissolved. In the past this power has been used almost cavalierly to oust State governments ruled by political opponents of the Centre. In 1994, the Supreme Court, in the Bommai case, laid down guidelines as to the circumstances in which Article 356 can be invoked; the power to impose President's rule should be a last resort, to be used very sparingly.

Article 253 explicitly empowers the federal government “to make any law” to implement any treaty or agreement with “any other country or countries”. Mamata Bannerji's reservations notwithstanding, there would thus seem to be no constitutional bar for the Indian government to sign an agreement with Bangladesh on the sharing of the Teesta waters. No government, though, would wish to ruffle a pivotal, if also prickly, political ally.

Bangladesh, like both Britain and India, is a parliamentary democracy, and, like Britain, a unitary State. The President is the constitutional Head of State, and all executive actions of the government are taken in his name. Except in the appointment of the Prime Minister and the Chief Justice, the President, in the exercise of his functions, acts “in accordance with the advice of the Prime Minister”. Executive power is exercised “by or on the authority of the Prime Minister”. The primacy of the office of Prime Minister is thus clearly underscored in the Bangladesh constitution, much more so than in Britain or India. As per Article 70, an MP forfeits his seat, if he votes against the position of his party in Parliament. In India a similar provision was enacted into law in 1985, by the 52nd amendment, to strengthen party discipline over a Member of Parliament.

Dag Hammarskjold once observed that the “end of all political effort must be the well-being of the individual in a life of safety and freedom”. A democratic polity is perhaps the only viable, long-term and self-sustaining means to this end. This is so because representative governments are accountable and have to face the electorate every few years. There is also a certain transparency in decision-making. Democracy, to be sure, does have deficiencies. Lord Hailsham, who was a contender for the leadership of Britain's Conservative party in 1963, and later served as Lord Chancellor, felt that democracy was the most acceptable political system devised by man, but also “appallingly clumsy, unfair and wasteful”. William Y Elliot, who taught at Harvard and also served in high councils of Government, likened democracy to a “water-logged old scow”, which does not “get very far very fast”, but does not sink either. And Harry Truman, in a lecture at Columbia University in 1959, famously declared that whenever “you have an efficient Government, you have a dictatorship”. According to some scholars, democracies in developing countries have to contend with four elements to achieve optimum results from the system, namely, instability, corruption, violence and poverty. Development and prosperity are not inevitable for a country, but eminently achievable, given good governance, honest endeavour and enlightened policies.

Late in the 18th century, future US President, James Madison, writing in The Federalist, articulated the view that the government was “greatest of all reflections on human nature”, and that “if men were angels no government would be necessary”. However, in a government “to be administered by men over men”, government must be enabled “to control the governed”, and then be obliged “to control itself”. The greatest danger to popular government, he felt, was “the violence of faction”, i.e. political parties. Madison's concerns are not irrelevant even in modern times.

A constitution has to be tailored to the needs and psyche of a people and nation. As Rousseau argued in the mid 18th century, the kind of government that is natural to one country may not suit another so well. Earlier, Alexander Pope had underscored another -- and a most vital -- aspect of governance when he wrote:

“For forms of government let fools contest;

Whate'er is best administered is best”.

Megasthenes is an eminent Bangladeshi columnist.