Inside

Original Forum |

| Causes of RMG unrest -- Refayet Ullah Mirdha |

| Who Pushes the Price up? -- Asjadul Kibria |

| Padma Bridge: Dream vs reality -- Mohammad Abdul Mazid |

Self-financing Padma Bridge -- Nofel Wahid |

| Unaccountability in Private Medical Services -- Mahbuba Zannat |

Medical Waste --- Mushfique Wadud |

Abysmal state of Emergency Medical Services |

On Clinical Negligence -- Eshita Tasmin |

The Population Growth Conundrum -- Ziauddin Chowdhury |

| Rohingyas and the 'Right to Have Rights' -- Bina D' Costa |

| Two-State Solution: Israeli-Palestinian Peace -- Dr Kamal Hossain |

| Forms of Government -- Megasthenes |

A Letter from Alghamdy and War Crimes Trial |

A letter from Alghamdy and war crimes tribunal

TUREEN AFROZ takes issue with a former Saudi diplomat's plea to stop the ongoing war crimes trial.

Courtesy

Courtesy

The Saudi Gazette is one of the largest and most read newspapers in Saudi Arabia. A few months back, it published an opinion piece, written by one Dr Ali Alghamdy, identified as a former Saudi diplomat who claims to have served in Bangladesh. In his article, he claims that he personally knew the former Prime Minister of Bangladesh, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as well as his daughter, the current Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. The purpose of Alghamdy's write-up was to urge Sheikh Hasina, the Prime Minister of Bangladesh, to order the release of accused war criminals who are now facing (or awaiting) trial in Bangladesh under the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act, 1973.

Alghamdy, in his article, advocates the war criminals' release on five grounds. He claims that these grounds merit immediate consideration by the Prime Minister of Bangladesh in order to show 'mercy' and to do 'justice'. It is well known a fact that the diplomats are the best practitioners of international law. Dr. Alghamdy's article, however, is found to have stood against all kinds of international legal norms and practices, which is least expected of a retired diplomat.

Trial of war criminals under Bangladesh's domestic law International Crimes (Tribunals) Act, 1973 is very much within the national jurisdiction of the state. Under international legal norms and practices, to manipulate or influence the domestic trial of a national court would be deemed as interfering into the internal affairs of the state. The international community must thus restrain itself from such unacceptable interference into the internal affairs of a state. Moreover, there is no way any person or organization, whether of Bangladesh or foreign nations, can try to influence any trial when the very trial is in progress.

The first ground on which Alghamdy argues that the ongoing war crime trials should be stopped in Bangladesh is that Bangladesh must 'forgive and forget' the crimes committed during 1971. He further argues: '(Sheikh Mujibur Rahman) issued several laws including the war crimes law by which 195 Pakistani military officers were convicted. The law did not include any Bangladeshi civilian or politician. Besides, the 195 officers were later pardoned, thus your father won the praise and admiration of the entire Muslim world. At the time, he made his famous statement: "I want the world to know that Bangladeshis can forgive and forget".'

Alghamdy's first ground is ill-conceived and based upon outright distortion. This is because,

(a) The said 195 Pakistani military officers did not have to go through any trial in Bangladesh whereby they were convicted and later pardoned. These 195 Pakistani millitary officers were prisoners of war and they were returned to Pakistan government authority on the understanding that they would face trial in their own land. International crimes such as genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes etc. have 'universal jurisdiction' and as such, can be tried by any state of the world, irrespective of their places of occurrence. I do not therefore see any wrong under international law and practice in taking such a stand by the then Bangladeshi government.

(b) Alghamdy claims that Bangladesh government, soon after its independence from Pakistan, issued several laws including war crime laws; however, none of these included Bangladeshi civilians or politicians. It is not at all clear as to why trial of war criminals would include civilians or politicians, whether of Bangladesh or of Pakistan. Being a civilian or politician is never a crime. It is only when civilians or politicians are found to have participated in an armed conflict that they would lose their 'protective status', and therefore, cannot be termed as civilians any more (Geneva Convention IV). Bangladesh accessed to the Geneva Convention in 1972 whereas Saudi Arabia adopted it in 1963. This is much earlier than Bangladesh which is why one should naturally expect a Saudi diplomat to be an expert on international laws and customs.

(c) According to Alghamdy, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman 'won the praise and admiration of the entire Muslim world' by his policy of forgiving and forgetting the war criminals. It is stated that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman government had never forgiven the war criminals, including the 195 Pakistani prisoners of war. The Tripartite Agreement dated 10 April 1974, signed by by Bangladesh, India and Pakistan was a result of a long-time negotiation between Bangladesh and Pakistan on the issues of trial of war criminals and the relevant repatriation process between these countries. History testifies that,

i. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, soon after his return from captivity on 10 January 1971, initiated a formal process of war crimes trial in Bangladesh. On 29 March 1972, Bangladeshi government announced a formal plan to try some 1100 Pakistani military prisoners, including senior officials like A A K Niazi and Rao Forman Ali Khan, for war crimes ('Bangladesh Will Try 1100 Pakistanis', The New York Times, 30 March 1972, p. 3). However, Pakistan exerted continuous pressure on Sheikh Mujibur Rahman government to hand over 195 prisoners of war to the Pakistani government.

ii. One of the ways the Pakistan government created pressure was by taking almost 400 thousand Bangladeshis who lived in Pakistan as hostages ('Pakistan Denies Charge', The New York Times, 17 April 1972, p. 6; 'Official Reports 2,000 Bengalis Held in Pakistani Jails', The New York Times, 13 December 1972, p. 3; 'Wave of Bengalis fleeing Pakistan', The New York Times, 12 November 1972, p. 10; 'Official Reports 2,000 Bengalis Held in Pakistani Jails', The New York Time, 13 December 1972, p. 3).

iii. Pakistan also convinced China to cast its veto on 25 August 1972 in the Security Council when Bangladesh was desperately longing for United Nations membership (S M Burke, 'The Postwar Diplomacy of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971' (1973) 13(11) Asian Survey 1036, p. 1039; 'A Veto By Peking', The New York Times, 27 August 1972, p. E3).

Photo Star

Photo Star

iv. There was also a clear threat from Bhutto that if Bangladesh carried out the trial of the 195 Pakistani prisoners of war, Pakistan would also hold similar tribunals against the Bangladeshis trapped in Pakistan and accordingly, Pakistani government seized 203 Bengalis as 'virtual hostages' for the 195 Pakistani soldiers ('Bhutto Threatens to Try Bengalis Held in Pakistan', The New York Times, 29 May 1973, p. 3; 'India-Pakistan Talks Reach Impasse', The New York Times, 26 August 1973, at p. 3).

v. Fearing the fate of 400 thousand Bengalis kept as hostages in Pakistan and to gain much-needed membership to the United Nations, Bangladesh finally accepted Pakistan's proposal mentioned in a statement issued in the last week of April 1973 whereby the latter claimed nationality jurisdiction over 195 Pakistani prisoners of war. The statement said: '…the alleged criminal acts were committed ... by citizens of Pakistan. … Pakistan expresses its readiness to constitute a judicial tribunal of such character and composition as will inspire international confidence to try the persons charged with offenses.' ('Pakistan Affairs', May 1, 1973, cited in S M Burke, 'The Postwar Diplomacy of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971' (1973) 13(11) Asian Survey 1036, p. 1040).

vi. Therefore, the 195 prisoners of war were not freed by the then government of Bangladesh without charges of war crimes; rather those 195 Pakistani prisoners of war were handed over to Pakistan, so they could be prosecuted by the Pakistani authorities.

As a second ground, Dr. Alghamdy argued that politicians can never be tried for committing genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. In support of his argument, he states that:

'(Sheikh Mujibur Rahman) never leveled charges (of genocide, crimes agianst humanity, war crimes, etc.) against any politician. When (Sheikh Hasina) became the Prime Minister following the 1996 elections, (she) did the same.'

His second ground is marked by two major fallacies. These are related to: (a) trial of politicians for committing genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, etc; and (b) time limitation of trial for these crimes. These two issues are discussed below.

(a) It is a general principle of law as recognised under article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice that nobody is above the law (natural law doctrine). Also, Rule of Law, in general, demands guarantee of equality before law and right to get equal protection of law (A V Dicey). In the circumstances, why would politicians be treated separately if they are found to have committed crimes? Under international law, there are a number of cases decided by the international courts where civilians (including politicians) were convicted for the said crimes. Their liability was imposed under both individual criminal responsibility and superior responsibility. Even if the civilian leader was found not to have ordered, solicited, aided, abetted or assisted the commission of a crime (i.e. absence of individual criminal responsibility), he was made liable under superior responsibility. For example, the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg) convicted Friedrick Flick and Herman Roechling (both were industrialists) under superior responsibility. Similarly, the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (Tokyo Tribunal) convicted foreign ministers, Hirota and Shigemitsu. The International Crimes Tribunal for the Former Yuguslavia (ICTY) upheld civilian conviction under superior responsibility in Prosecutor v. Delalic (1998) and Prosecutor v. Alecsovski (1999). The International Crimes Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) gave similar convictions under superior responsibility in Prosecutor v. Kambanda (1998), Prosecutor v. Serushago (1999), Prosecutor v. Musema (2000), Prosecutor v. Kayishema and Ruzindada (2001), Prosecutor v. Nahimana (2003) and Prosecutor v. Bikindi (2008).

(b) According to Alghamdy, if someone has not been previously tried for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, etc, he cannot be put into trial now. Essentially, the legal question here is that is there a time limitation for trying someone involved with these crimes. According to the Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity, 1968, there is no time limitation for trying war crimes and crimes against humanity. Further, Article 29 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, 1998 provides that 'The crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court, including genocide, shall not be subjected to any statute of limitations'. Therefore, Alghamdy's argument that since Sheikh Mujibur Rahman during his term and Sheikh Hasina during her previous term did not try the politicians for these crimes; such a trial cannot take place does not wash. Such a ground as a basis for stopping the ongoing war crime trials in Bangladesh is inherently flawed and against the international law, customs and jurisprudence.

Another ground of Alghamdy encompasses the real purpose of writing his article. It essentially argues that the arrest of Muslim leaders like Ghulam Azam is unjust as no one would believe that they (including Ghulam Azam) could commit crimes against humanity, inter alia.He states:

Courtesy

Courtesy

'Nothing can justify the unjust decision to arrest Muslim leaders ... many Muslim leaders all over the Muslim world are upset about the arrest of Muslim groups and leaders such as Professor Ghulam Azam who was accused of charges that no one would believe. He was charged with things that were done 40 years ago. He was not charged with them at the time.'

He in his article claims knowing Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Sheikh Hasina. However, he did not at all reveal his existence or extent of relationship with the Muslim leaders of Bangladesh, including Ghulam Azam. It may well be so that he does not know Ghulam Azam or any muslim leader of Bangladesh, currently facing trials at the International Crimes Tribunal. How can he, then, guarantee the innocence of Muslim leaders of Bangladesh, including Ghulam Azam?

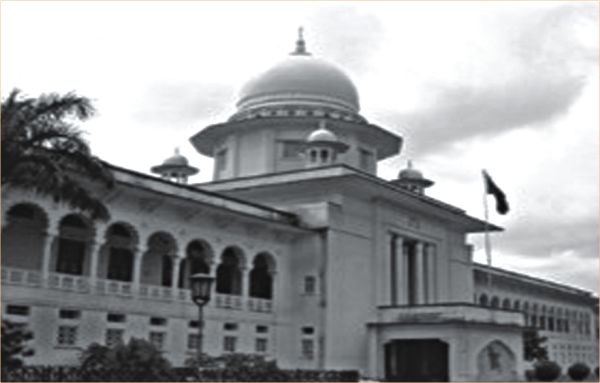

Moreover, Bangladesh, after almost 40 years of independence, has initiated a trial process for the accused criminals of genocide and crimes against humanity at the International Crimes Tribunal, Dhaka. It is a judicial process where convictions will be made only upon satisfactory, proper evidence. There is absolutely no scope for the said tribunal to reach a decision on the basis of opinion and views, whether of someone in Bangladesh or abroad. Therefore, whether the trial or its ongoing process makes the leaders of the Muslim world upset or not, the trial must ensure justice by being fair and impartial.

Alghamdy, being a practitioner of International Law, must know that crimes of genocide etc are considered to be the most serious crimes of concern to the international community. It is thus stated in the preamble of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, 1998: '(such) crimes … must not go unpunished and that their effective prosecution must be ensured by taking measures at the national level and by enhancing international cooperation'. Therefore, the international community is 'determined to put an end to impunity for the perpetrators of these crimes and thus to contribute to the prevention of such crimes' and further, it is stated at the Preamble that 'it is the duty of every State to exercise its criminal jurisdiction over those responsible for international crimes'. In the circumstances, it is not clear as to why Alghamdy has been so adamant in creating an exception for the Muslim perpetrators claiming that Muslim leaders of Bangladesh, including, Ghulam Azam, cannot be tried for international crimes.

|

|

Munir Uz Zaman/drik |

There is also another aspect of his argument which clearly puts him in a position to violate all norms and practices of international law. Is he suggesting that Muslims can never commit genocide or crimes against humanity and thus, trial of any accused Muslim perpetrator in Bangladesh will make leaders of the Muslim world upset? In my view, such an indication begs several questions: Why should any international crime, if committed by Muslim leaders in any part of the world, go unpunished? Is it so because that might, as Alghamdy claims, make the Muslim leaders of the world upset? Or just because the crimes were committed 40 years ago even though the limitation law under international legal jurisprudence does not support that contention? In fact, he is claiming a blanket immunity on the ground of religion to all Muslim leaders of Bangladesh even if they were involved with international crimes. This is totally unwarranted; Bangladesh is constitutionally committed to respecting the principles of international law (Article 25 of the Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh). Therefore, the ongoing trial of international crimes must continue as a measure to put an end to impunity for the perpetrators of those crimes, whether Muslim or not, and thus contribute to the prevention of such crimes happening in Bangladesh in future.

His fifth and final ground is that Sheikh Hasina must reconsider her decision to try the accused criminals of international crimes and must immediately release them in order to win people's appreciation and to show her deep love for her late father. Sheikh Hasina, or for that matter any prime minister of Bangladesh, is under oath to act only and only under the provisions of the Constitution. To ensure and uphold the rule of law, she cannot just do something only to win people's appreciation or to show her love for her late father.

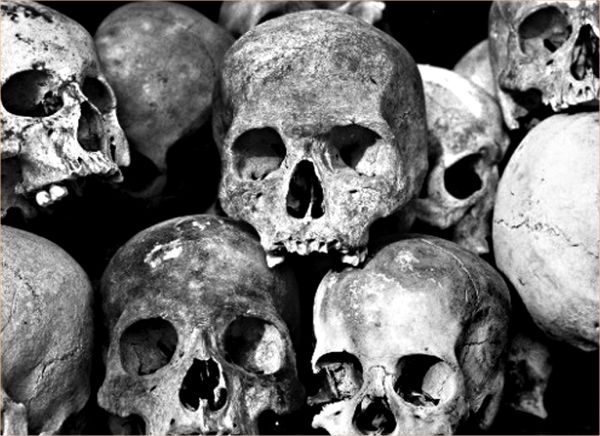

In conclusion, it is not at all clear as to why Alghamdy has conceived the entire trial of war criminals in Bangladesh as only a family matter of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his daughter Sheikh Hasina. The trial of war criminals of 1971 is a national issue for Bangladesh; officially three million Bengali people were killed and 200 thousand Bengali women became victims of sexual offences in Bangladesh duing 1971. Many more were tortured, dislocated and has economically suffered. Since 1971, the victims and their families in Bangladesh have been waiting for justice. The sufferings and sacrifice of this nation cannot be undermined by simply writing a wishful letter to Sheikh Hasina requesting her to forget and forgive. Being professionally a diplomat and thereby, a practitioner of international law, he has violated the basic principles of international law, customs and culture. His letter to Sheikh Hasina is nothing but a gross violation of international legal norms and practices.

Barrister Tureen Afroz is an Associate Professor of Law at BRAC University, Bangladesh and the Member-Secretary of the Platform for Supporting International Crimes Tribunal, Dhaka.