Inside

|

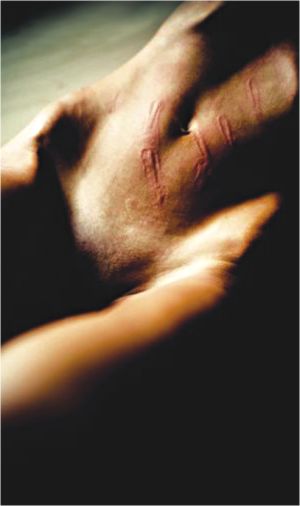

The Power Of Forever Photography/vetta-getty Images

The Power Of Forever Photography/vetta-getty Images

Putting an End to Fatwa Violence

Rural, poor women are the most vulnerable victims of fatwa violence despite their fundamental rights being protected by the law, states ARAFAT HOSEN KHAN.

The primary identity of a Bangladeshi, male or female, is citizenship, whose basic definition offers a promise of equality and justice within the nation's democratic constitutional framework. Repeatedly, however, this promise is undermined by the masculinity of nationalist ideology, the fiction of citizenship and the malleability of law. Instead of offering an alternative space, the nation often simply functions as an extension of family and community structures and defines women as belonging in the same way as their structures and therefore, women are the most neglected members of the society and have very little voice, even within the home/family. As a result, they are consistently becoming easy victims of all sorts of violence. Furthermore, women need to be protected from vested interest groups and acts of impunity towards them by those purporting to protect society and must be dealt with seriously and in accordance with the law.

Women in Bangladesh are some of the most vulnerable in the world. Although women leaders, Sheikh Hasina and Begum Khaleda Zia, have been governing Bangladesh since 1991, ordinary women have not obtained complete rights and security. In the year 2000, the United Nations rated Bangladesh as having the worst record of violence against women in the world. The UN Human Development Report 2004 listed Bangladesh as ranking 110th out of 144 countries with respect to the gender-related development index. However, the situation is now somehow much better than before.

Legal empowerment helps disadvantaged population take control over their lives through a combination of legal education and action. The success of legal empowerment work is measured by looking for indicators of change that demonstrate improvements in the lives or positions of women or girls in some way. Litigation is one of the main tools for women's legal empowerment and this can be clearly identified by various Judicial pronouncements i.e. judgments on sexual harassment, fatwa, etc.

Fatwa is becoming an everyday story in Bangladesh and it is very unfortunate to observe its misuse by a section of village elders who have no or little knowledge about Islamic law and who are in no way eligible to pronounce fatwa. From the early 1990s, the incidence of fatwa being issued by rural clerics or village elders and resulting in corporal punishment being inflicted on women and men drew increasing attention from the media and human rights organisations nationally and internationally. The suicide of Nurjahana in remote Chatokchara, in the northern district of Moulvibazar, following the execution of a fatwa which required her to stand waist deep in a pit and be pelted with stones by fellow villagers including her own family, catalysed a national response. Mohila Parishad held an on-site investigation and closely monitored the criminal proceedings instituted against the cleric and the participants in the shalish who issued the fatwa. They continued to monitor the appeal hearing, and ultimately their convictions were upheld and they were sentenced to seven years' imprisonment each. Nurjahan's death was rapidly followed by several other egregious cases of what increasingly came to be known as 'fatwa violence '.

In this context, almost a decade after the focus on fatwa violence first began, in December 2000, the High Court issued a Suo Motu order on certain government authorities on the basis of a newspaper report about another fatwa requiring a woman to undergo an intervening marriage (hilla) on the ground that she had dissolved marital ties with her husband. Acting upon this fatwa, a relative of the woman then reportedly had sexual relations with her, and her husband refused to take her back as his wife.

|

|

Valentin Casarsa/vetta-getty Images |

On December 2, 2000 a Suo Motu Rule in Writ Petition No. 5897 of 2000 was issued by the High Court Division arising out of a newspaper report published in the Daily Banglabazar Patrika which stated that Shahida, wife of Saiful (son of Golam Mostafa), of village Atiha under Police Station Sadar Upazilla, District Naogoan had been forced to marry her husband's paternal cousin Shamsul in accordance with the pronouncement of a fatwa by one Haji Azizul Huq which purported to hold that Shahida's marriage to Shamsul had been dissolved consequent to an incident one year previously when her husband uttered out of anger the word "talak" notwithstanding the fact that Shahida and Saiful had continued their married life in the meantime. The said report further stated that after Saiful heard about the forced marriage to Shamsul, he refused to accept Shahida as his wife and sent her to her father's house where she was living a life of misery and anguish. Then the High Court Division issued the Suo Motu Rule 'upon the District Magistrate and Deputy Commissioner of Naogaon to show cause as to why he should not be directed to do that which he is required by law to do concerning the said incident and/or pass such other or further order or orders as this Court may deem fit and proper.' The High Court Division further directed the District Magistrate and Deputy Commissioner, Naogaon to appear in person and to produce the said Haji Azizul Huq before the Bench on December 14, 2001.

After hearing the parties, the High Court Division on January 1, 2001 pronounced its judgement making the rule absolute and holding that the marriage of Shahida and Saiful was not dissolved and that even if the marriage was taken as being dissolved there was no legal bar upon Shahida from re-marrying Saiful without an intervening marriage with any third person; that the fatwa in question was wrong and further holding that any fatwa including the instant one are all unauthorised and illegal. The Hon'ble Court also opined that that the legal system of Bangladesh empowers only the Courts to decide all questions relating to legal opinions regarding Muslim laws and other laws as in force. This was a great day for Bangladeshi women who are the victims and sufferers of fatwa.

However, very unusually, two appeals were filed against this judgement, by third parties (who had had no involvement in the High Court case). The Government did not appeal the judgement, nor did it take part in the leave hearing. One of the leave petitioners is an Assistant Mufti at a madrasah, described as being engaged in imparting Islamic Higher Education. The other is Chairman of the Mosjid Council, and claims to be a scholar of Islamic Jurisprudence and the Holy Quran and Hadith, who is regularly asked for advice on Muslim family matters and other aspects of Muslim life and in the process issues fatwas and as such has an interest in the matter.

The apex court has granted leave to appeal in both petitions, on the ground that it is necessary to consider the following points:

a. Whether there is scope for the High Court Division to issue a Suo Motu Rule in the exercise of its jurisdiction under Article 102 of the Constitution;

b. Whether some of the decisions of the HCD sought to be appealed are in conflict with the guaranteed rights of freedom of thought and freedom of religion; and

c. Whether the High Court Division has exceeded its jurisdiction in making recommendations in respect of matter which are contrary to the basic principle of separation of powers as exists in the Constitution.

In these circumstances, while appeal hearing of the above mentioned Suo Motu case on fatwa was pending regarding the fatwa case before the Apex Court of Bangladesh, the incidents of fatwa against poor women in Bangladesh increased alarmingly. Throughout 2009, newspapers reported a series of incidents of violence inflicted on women and girls in the name of fatwa by traditional dispute resolution processes (shalish), often involving religious leaders. These incidents had reportedly resulted in women and girls in villages across the country being caned, beaten, lashed or otherwise publicly humiliated within their communities. They included:

* a woman in Comilla subjected to 39 lashes and hospitalised after a shalish over a dispute regarding acknowledgement of paternity of her child born out of wedlock

* a woman and man in Hobiganj subjected to 101 lashes for 'breaching social norms'

* a woman subjected to 101 lashes for refusing her uncle's sexual advances

* the wife of a madrasah teacher in Naogaon district subjected to a hilla marriage; she and her husband were subjected to 101 lashes and then refused medical treatment after he reportedly pronounced talak

* a woman in Srimongol subjected to 101 lashes for 'talking to a man on the road'

* a woman in Nilphamari district who had her hair forcibly cut and was compelled to leave her village with her two children for refusing sexual relations with a locally influential person, the son of the elected Union Parishad Chairman

* a woman's family which was ostracised from their village due to their refusal to submit her to a hilla marriage after her husband pronounced a divorce. Their son was forced to leave the local madrasah, and the local mosque refused to allow them to share iftar (the evening meal when Muslims break their fast during the Islamic month of Ramadan).

The spate of acts of violence against women in several parts of rural Bangladesh are justified by the perpetrators of these crimes on the basis of fatwa given by a local imam or a maulvi or maulana. It has been rightly pointed out that violence against women is a crime that cannot be justified on this basis. In addition, and again rightly, it is pointed out that these self-appointed givers of fatwa have no authority for their proclamations. What these statements however fail to clarify is a fundamental misconception about fatwa themselves.

The practice of the issuance of fatwa which does not have any legal authority and is an imposition of extra-judicial punishment by self-proclaimed religious leaders and influential people in the rural areas in Bangladesh was a common matter. Despite sporadic responses from law enforcement agencies, and in some cases high-level interventions by the Prime Minister's Office providing medical treatment to the survivors, no systematic efforts were undertaken to address such cases. In July 2009, a constitutional challenge was filed by five human rights women's rights and legal services organisations (Ain o Salish Kendro (ASK), Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust (BLAST), Bangladesh Mohila Porishad, BRAC and Nijera Kori) against the state's failure to take action to prevent such incidents or to investigate them, and to prosecute and punish those responsible. The petition was filed following several newspaper reports and investigation by the petitioners revealing stories of horrible torture inflicted on the rural people, especially women, in the name of religion by local religious leaders and powerful corners. A number of deaths, suicidal incidents out of humiliation and grievous hurt were reported arising from punishment given in shalish, but the law enforcing agencies took no action to prevent these illegal actions.

All of the above incidents of fatwa, in which poor and vulnerable women and men in rural areas across the country have been subjected to whipping, lashing and beating following the pronouncement and execution of certain penalties, by individuals acting without any authority of law, have all clearly resulted in the commission of crimes punishable under applicable laws including the Bangladesh Penal Code 1860 and the Nari o Shishu Nirjaton Domon Ain 2000.

Although the government and all citizens have clear obligations under law to prevent the commission of crimes, such obligations with regard to local government officials are elaborately set out in the Union Parishads Ordinance 1983 which sets out the powers and functions of the Union Parishads in particular to maintain law and order and prevent the commission of crimes, as well as the powers and functions of government in issuing directions and standing orders as necessary for the purpose of the Ordinance, in particular in Sections 30, 32, 38, 61 and 62 as well as in the Schedules thereto.

Such extra-judicial punishments such as whipping and lashing and caning as well as forced ostracism within the village constitute grave and egregious violations of the fundamental right to freedom from torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading punishment as guaranteed under Article 35(5) of the Constitution and the imposition and execution of such extra-judicial punishments by persons acting without any authority of law clearly constitutes a violation of the fundamental right of all persons to be treated in accordance with law, as guaranteed under Article 31 of the Constitution.

The state's obligations to ensure protection of this right are both negative, that is to refrain from subjecting any person directly to torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading punishment, and also positive, that is requiring the State to take effective measures to ensure that no person is subjected to torture, cruel, degrading or inhuman punishment and to prevent any such incident from occurring. The measures that may be taken to prevent such incidents include raising awareness among all individuals concerned that the imposition and pronouncement of penalties by any person acting without authority of law, including in the name of fatwa is clearly a criminal offence, through dissemination of such information through the media and through the medium of education, as well as through specific circulars and government orders or standing orders to be issued to the concerned authorities.

In a landmark judgement for women's rights, the High Court declared that '' Imposition and execution of extra-judicial penalties including those in the name of execution of Fatwa is bereft of any legal pedigree and has no sanction in laws of the land. '' The Court directed that persons responsible for imposition of extra-judicial punishments and their abettor(s) shall be held responsible under the relevant sections of the Penal Code and other laws. It further directed the law enforcing agencies, Union Parishads and Pourashavas (municipalities) to take preventive measures against the issuing of such fatwas in their concerned areas, and to take legal steps for prosecution in case of such occurrences, as appropriate. They directed the Ministry of Local Government to inform all law enforcing agencies, Union Parishads and Pourashavas of the unconstitutional nature of such penalties. In a particularly significant step, they directed the Ministry of Education to introduce educational materials in the syllabi of all educational institutions particularly in madrasahs on the supremacy of the Constitution and rule of law.

Finally, after more than 10 years, the Supreme Court of Bangladesh started hearing on the appeal on 01.03.2011, where lawyers against fatwa/extra judicial penalties argued that the pronouncement and execution of certain fatwas, including those which involve corporal punishment or other forms of humiliating and degrading treatment, is a criminal offence under Bangladesh law, and therefore these appeals raise issues regarding the enforcement of existing criminal laws to protect (primarily women) from violence, and that such fatwas cannot be protected as part of the right to freedom of religion.

Earlier on February14, 2011, the Supreme Court appointed nine legal experts as amicus curiae (friends of the court) for their opinion on this issue. It also heard the opinions from five of the country's prominent Alems (Islamic scholars), nominated by the Islamic Foundation Bangladesh. The panel of five, however, told the court, banning fatwa will ultimately put a ban on the holy religion of Islam. As a result, all the people of the State would become sinners for lack of adequate knowledge on Islam.

After hearing all the concerns in this case, the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh on May12, 2011 ruled that fatwa or religious edicts could only be pronounced by persons properly educated in religious matters, but no one could be forced to accept it, in the following terms:

"No person can pronounce a fatwa which violates or affects the rights or reputation or dignity of any person which is covered by the law of the land,"

It added:

"[A] fatwa on religious matters only may be given by the properly educated persons which may be accepted only voluntarily but any coercion or undue influence in any form is forbidden."

The judgement further pointed out that

"no punishment including physical violence or mental torture in any form can be imposed or implicated on anybody in pursuance of [a] fatwa."

The abovementioned verdict of the Apex Court of Bangladesh in the fatwa case and the High Court judgement against fatwa and related advocacy work against fatwa, are definitely one step forward in order to protect women's rights in Bangladesh and this would eventually lead to incremental achievements for legal empowerment of women in the country.

The judgement in the fatwa case demonstrates the positive approach by the judiciary and substantiates the inalienable fundamental human rights irrespective of gender. In an egalitarian society like Bangladesh where majority of the population are Muslim, the judgement in fatwa case indubitably connotes as a positive modus operandi to purge the pseudo-religious psyche in masquerade of Islamic Sharia. No rights in an organised society can be absolute. Enjoyment of one's rights must be consistent with the enjoyment of rights by others. Every person has a fundamental right not merely to entertain religious belief of his choice, but also to exhibit this belief and ideas in a manner which does not infringe the religious right and personal freedom of others. The fusion of culture and religion always tend to conflict the moment one tries to impose it on others as of rights. The judgement in the fatwa case can very well be signified as a reckoning that to establish the rule of law and ensure the proportionality within the society by preserving the rights of each and every individual irrespective of their gender appreciate only the state authority has the power to do so. Society never allows anyone to manifest or practise anything erratically that encroaches upon the inherent rights of other individuals.

The road ahead is full of difficulties and discomforts. But we should welcome the challenges and also the opportunity that has been created by the judiciary for the betterment of women and girls in our country who are still the most vulnerable and we should pledge our best efforts -- all we have in material things and physical strength and spirit -- to see that freedom advances and that they are sheltered by the rule of law and their rights are protected.

Arafat Hosen Khan is Barrister - at - Law, The Honorable Society of Lincoln's Inn and with Dr. Kamal Hossain and Associates. He can be reached at barrister.arafat.h.khan@gmail.com.