Inside

Original Forum |

| Readers' Forum |

| Our War Crimes Trials: Making it Happen -- Ziauddin Choudhury |

| Putting an End to Fatwa Violence -- Arafat Hosen Khan |

| Girl on Girl: How we perpetuate abuse and violence -- Shahana Siddiqui |

| The Price of Violence -- Interview with Dr. Julia Ahmed |

| Equal but Different: Gender discrimination in immigration rules -- Farah Huq |

The Crime Never Considered a Crime --- AZMM Moksedul Milon |

Women in the Workplace: Gender-specific challenges in the corporate world --- Olinda Hassan |

Women's sports in Bangladesh -- An Encouraging Year -- Naimul Karim |

| Her vindication, he supports -- Shayera Moula |

| An Aconcaguan Birth --Wasfia Nazreen |

| On Objectification of Women in Mainstream Hollywood Movies --Rifat Munim |

| Silence of the Voices --Zoia Tariq |

Equal but Different:

Gender discrimination in immigration rules

FARAH HUQ takes on the case of gender-biased immigration laws in Bangladesh.

'Women are equal, but different'

That has been the popular liberal guise for a conservative apologist. And it is the endorsement of such thinking that allows implicit and explicit discrimination to persist in Bangladeshi governance and policies till today.

The idea of women's rights is nothing new. It has been fought for, popularised by the media, legislated upon, debated upon, misunderstood, accepted and upheld in various degrees by most of the governments of the world. Including Bangladesh. Enshrined in our Constitution at

Articles 27 and 28 is the guarantee for men and women to the fundamental right of equality before the law and freedom from gender-based- and other forms of- discrimination. Article 28(2) specifically states that:

"Women shall have equal rights with men in all spheres of the State and of public life"

In addition, Bangladesh has acceded to various international Conventions, including UN Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) 1979, which have brought to the forefront the issues of women's empowerment in policy- and law-making.

And so it was quite shocking when I learnt of an ongoing public interest litigation case wherein certain women Bangladeshi nationals are petitioning the government to amend or declare invalid an immigration rule that is so clearly discriminatory that it is unbelievable it still exists. This is in relation to the granting of a No-Visa-Required (NVR) status, or the right to residence and to work in Bangladesh, to spouses of Bangladeshi nationals. The rule provides that the NVR will be granted to the foreign wives and children of Bangladeshi nationals. But no provision is made anywhere in the existing Visa Rules for issuance of NVRs to foreign husbands of Bangladeshi nationals. This effectively means that a Bangladeshi woman cannot avail of having her husband live with her in her country of origin without immigration control. The topic may be seen as a niche one; possibly only a handful of Bangladeshi women will be affected by it, but the rule is indicative of a prevalent bias that still seems to exist in the mindset of the Bangladeshi government officials who have failed to change this rule to this day.

Women have notoriously faced such discrimination when it comes to the issue of transmitting their citizenship to foreign husbands, or to children born from a foreign husband. Under Pakistan period laws, a woman's nationality (as well as the children's for that matter) was dependent on her relationship with her husband and/or father. And similarly a woman could not transmit her nationality to her husband or children. A host of excuses have been forwarded to justify discriminatory laws, such as the fact that domestic labour market needs to be protected, that dual nationality prevents one from being loyal to the nation, that there is a risk that foreign husbands will not have sufficient links with the countries of their wives, or that there are national security issues to consider. In Bangladesh, some officials have raised the issue that a Bangladeshi woman being married to a foreign national will be a problem as it will raise questions about the religion of the children and their being non-Muslims. This rather begs the question of whether the woman in question is marrying a foreign national who happens to be a Muslim or not!

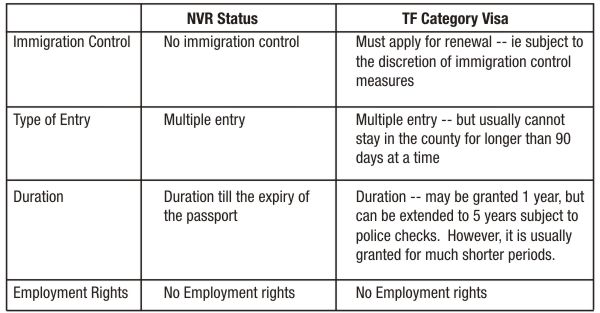

Although the government has recently amended the citizenship laws to make them non-discriminatory, the discriminatory rule regarding the NVR has been retained. I suppose, following the 'equal but different' principle, the Government of Bangladesh seems to think foreign husbands of Bangladeshi nationals are well provided for by the alternative of TF category visa. The comparison of the two is below:

The differences in the rights granted by the visas are clear. The effect of this rule is that it disables the foreign husbands of Bangladeshi female nationals from entering and inhabiting the country freely, which is clearly discriminatory and has a considerable impact on the enjoyment of family life of Bangladeshi female nationals. This acts as a restriction on her rights to cohabitation and family life with her husband; it restricts her choice of residency; it may even act as a restriction on her choice of marriage and other marriage-related decisions; and it certainly restricts her right to live with human dignity in her own country without arbitrary interference from the government. On the other hand, a Bangladeshi male national with a foreign wife will not face any of the above restrictions since his foreign wife will be issued with an NVR immediately upon application.

It is also clear from international jurisprudence that such discriminatory practices cannot be tolerated. It is broadly agreed that the State has a right to conduct immigration control in the way that it sees fit, and by that virtue is not obligated to grant entry, residency or citizenship to anyone until they are deemed fit; however, once a right has been granted by the government, the enjoyment of that right cannot be subject to gender-discrimination.

The Constitution of Bangladesh allows for non-arbitrary and reasonable interferences to be made in the fundamental rights of its citizens, as in this instance, the right to a family life. But how can it be considered to be reasonable to expect a woman Bangladeshi to be wholly at the mercy of the immigration authorities regarding whether she can enjoy her right to a family life? What possible justification is there for such barefaced discrimination in denying a woman a right that is readily given to a man?

It was only as recently as 2008/9 that the Government of Bangladesh brought in changes to the Citizenship Act of 1951 finally eliminating the discriminatory provisions that had prevented Bangladeshi women from transmitting their nationality to their husbands and their children. Now the law stipulates that a spouse (and not wives only) may gain citizenship after four years of marriage and residency, and that a child may derive their citizenship from both the father and the mother. This course of action is much welcomed and laudable, but it still begs the question why three years on, such a blatantly discriminatory rule in relation to NVRs can be found in the visa and immigration regime. There are a slew of cases currently pending in the Court where this rule has been challenged as being unconstitutional, arbitrary and discriminatory. The government has been asked for an explanation on this by the High Court. It is not yet clear what stand they will take. This is a real opportunity for the government to boldly assert its clear support for eliminating gender discrimination from the face of the law, and through doing so, move us further towards the goal of full equality.

1. Article 28(2), Constitution of Bangladesh

Farah Huq is Barrister-at-law and Research Fellow, Dr. Kamal Hossain & Associates.