Inside

Original Forum |

| Truth, a Casualty of War -- Irfan Chowdhury |

| On the Notion of Tolerance -- Shakil Ahmed |

| Violence -- Reversing the culture of impunity -- Manzoor Ahmed |

| Lessons from the Troika of Non-Violence: Gandhi, King and Mandela -- Ziauddin Choudhury |

Institution-Building or Rebuilding Institution? Focus on Bangladesh -- Dr. Mizanur Rahman Shelley |

Rethinking 'The Fear' --- Tapas Kanti Baul and Sultan Mahmud Ripon |

No Respite for Rohingyas |

Politics Not for the People -- Syed Ashfaqul Haque |

Marriages: Made in Heaven, Living Hell for Many -- Aruna Kashyap |

| Fighting a Lone Battle -- Naimul Karim |

| The Story of the Rise of Modern China -- Ashfaqur Rahman |

| Che: The legacy endures -- Syed Badrul Ahsan |

| Graduating Out of Exclusion -- Shayan S. Khan |

| The Dream Team --Megasthenes |

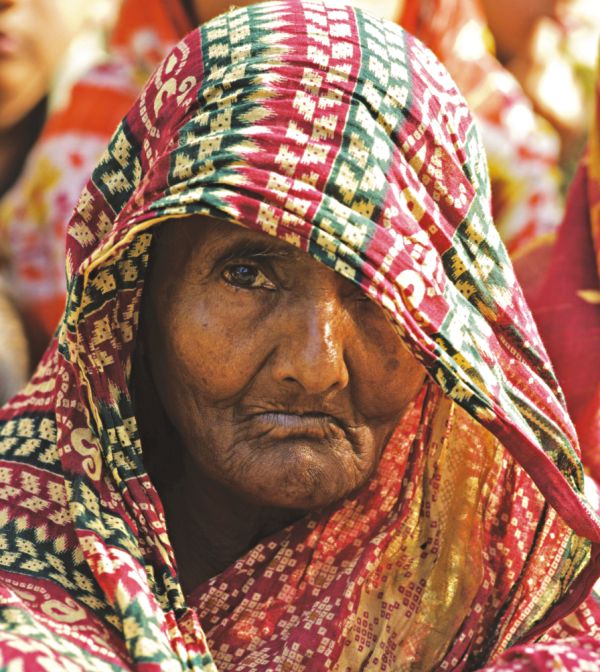

SHEHZAD NOORANI/BRAC

SHEHZAD NOORANI/BRAC

Graduating Out of Exclusion

Against the backdrop of International Day for the Eradication of Poverty (October 17), SHAYAN S. KHAN explains the concept of 'inclusive development' as a means to overcome extreme poverty.

The Bangladesh government has set ambitious targets for the reduction of poverty, including extreme poverty, in the country in time for the next elections. Figures from the Household Income and Expenditure Survey of 2010 indicated 31.5% of the population of Bangladesh was living below the national poverty line. With an election due in early 2014 at the latest, the government is aiming to reduce that number to 25% by 2013. This in turn is part of a longer term strategy to reduce poverty to just 15% by 2021, by which time it is envisioned that Bangladesh will enter the ranks of the “middle-income countries”.

Of the 31.5% below the national poverty line, BRAC estimates 23% to be living below the lower poverty line (BRAC Annual Report 2011). They are the ones who fall through the government's social safety net, and are even unable to access mainstream development schemes such as microcredit. The lowest 8% in particular, live in conditions of extreme hardship, characterised as “chronic extreme poverty”. This is a segment that has always existed in Bangladesh, as elsewhere in the world where poverty has reared its ugly head to build a wall between the haves and the have-nots. BRAC has always been troubled by the failure of their development initiatives to reach this segment, one of the reasons why it has never jumped on the bandwagon regarding microfinance as the panacea to curing all the world's ills, despite an extensive microfinance programme. BRAC realised very early on that resting on the laurels of microfinance would only work to perpetuate this segment's exclusion. And it is with this in mind that it started devising ways to tackle this exclusion as far back as the 1980s. It has been a battle that is just starting to bear fruit, fostering the kind of “inclusive development” called for in various critiques within the literature of development economics, not just in Bangladesh, but across the entire world.

Exclusive development

Look closely at the heart of the global financial system that emerged in the wake of the Industrial Revolution, and surely you won't fail to spot the inherent injustice that coloured its prominence right from the start. Whether or not you subscribe to the view that the system irrevocably broke its overflowing banks almost exactly four years ago now, on the day Lehman Brothers crashed to send the world economy into a tailspin it is still recovering from, what cannot be denied is the exclusionary, almost secretive nature of it all that tilted the balance disproportionately in favour of those with the greatest access to finance. In a world economy trapped within the boundaries of the zero-sum game prescribed by Pareto efficiency, this usually happened at the expense of those without the same access.

The role of finance, or rather access to it, in the system that emerged cannot be overstated, although it is only recently that it has started drawing the requisite attention. The UN's Millennium Development Goals originally contained no explicit mention of it, but a 2010 review recognised the importance of “financial inclusion and innovations in financial products” towards achieving the MDGs. During that year, discussion focused on examining how governments, business and multilateral institutions can work together to help the poor “build assets, increase incomes, and reduce their vulnerability to economic stress”.

Broadly defined, access to finance is the share of households and firms that are able to use financial services offered as part of the formal banking plus non-banking financial system, if they choose to do so. It can have a substantial effect on welfare and contribute significantly to poverty reduction. Odell (2010) refers to recent empirical evidence using household data that indicates even access to basic financial services such as saving, money transfers and credit can make “a substantial positive difference” in poor people's lives. For SMEs in poor countries, the principal obstacle to growth is often the lack of access to adequate finance. There is mounting empirical evidence that suggests increasing financial access is both pro-growth and pro-poor, that is, it promotes growth with less inequality. One study found that access to a savings account led after six months to a 39% increase in productive investment and a 13% increase in food expenditure among women micro-entrepreneurs in Kenya.

For a number of decades now, microfinance has played the role of mitigating some of the ills brought on by the disenfranchisement of the world's poor people from the global financial system. For all that it has done to empower women and challenge entrenched societal norms, the essence of the model lies in extending financial access to poor and excluded people. However, as noted by Syed Hashemi and Aude de Montesquiou in a focus note for the World Bank's Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP), microfinance “has not typically reached extremely poor people”. The vast majority of the world's 150 million microcredit clients are thought to live just above or just below the poverty line. That is an achievement in itself, and to be sure, not something to be scoffed at. For most of these people, the only other sources of finance are part of an informal lending structure that is not only more costly, but less reliable as well.

Beyond microfinance

Informed by its decades of experience fighting poverty on the frontline, BRAC has long recognised the limits of the microfinance model, having observed the failure of its own microfinance programmes to reach the poorest of the poor, those at the bottom rung of the economic ladder, the ultra-poor, as we now call them. As far back as 1985, BRAC partnered with the Government of Bangladesh and the World Food Program to add “a graduation ladder” to an existing national safety net programme providing the poorest households with a monthly allocation of wheat over a period of two years. In many ways, the Income Generation for Vulnerable Group Development programme, or IGVGD, was the precursor to today's Challenging the Frontiers of Poverty Reduction: Targeting the Ultra Poor (CFPR-TUP) programme that is drawing the attention of development practitioners the world over. For IGVGD, BRAC worked with the beneficiaries of the GOB-WFP programme by topping up the wheat allocation with skills, training, mandatory savings and small loans to accelerate livelihoods development.

Established in 2002, CFPR-TUP is a more fine-tuned version of this approach, benefiting from a more contextual definition of the ultra-poor (for Bangladesh, people who spend 80% of their total expenditure on food and yet cannot attain 80% of their standard calorie needs) and characterised by a more intensive, sequenced set of inputs designed to leave beneficiaries in a position, after two years, to avail other poverty reduction schemes such as microfinance and avoid falling through the government's social safety net. In effect, they “graduate” out of ultra-poverty.

SHEHZAD NOORANI/BRAC

SHEHZAD NOORANI/BRAC

By 2010, the CFPR-TUP programme had reached as many as 300,000 ultra-poor households,

and BRAC estimates that over 75% of these households are currently food secure and managing sustainable economic activities. As much as it is a road to microfinance, it doesn't force you through the gates of the formal financial system as well, mindful of the fact that many poor people remain averse to the idea of taking on credit. However, one of the core elements at the heart of the 'graduation model' underpinning the CFPR-TUP programme is savings. Although not mandatory, participants are “highly encouraged” to save regularly in a formal way, and this is said to help them build financial discipline and become familiar with financial service providers. Of course, providers also benefit from this, as most participants represent a new client segment for them.

Whether in the end participants in the programme do tend to avail microfinance as a next step towards financial inclusiveness depends mostly on the success of the livelihood initiative they were matched up with. The transfer of an asset to help participants “jump-start a sustainable economic activity” is said to be a critical element of the model. Market research is carried out to arrive at viable livelihood options particular to the programme area, before assets are transferred after matching the right activity to the interests and skills sets of participants. They are also provided with a period of skills training and regular coaching throughout the programme to help them make the best of the assets they gain. The programme wraps up by reclaiming all these assets (most commonly livestock) at the end of two years -- a key feature that guards against dependency by telling participants that support will end at some point and so they need to “graduate” to sustainable livelihoods by then. The asset transfer is meant to act as a “leg-up” that puts the onus on beneficiaries to create their own pathways out of poverty.

Post-graduation

BRAC clearly stipulates that “success” in its CFPR-TUP programme is achieved when households fulfill at least six of nine indicators associated with food security, diversified economic sources, asset ownership, improved housing and school enrollment. That means whether or not graduates avail the range of financial services that become available to them upon completion of the programme is not in itself a requisite for success. The goal is to ensure that by the end of the programme, members are creditworthy and in a position where they can access credit if they want to. However, Hashemi and Montesquiou (2011) note that financial services do have a role to play in participants' “trajectories beyond graduation”. Continuing to save after the end of the programme can help participants “protect assets and accumulate money for future investments”.

Possibly the most exciting, and useful manifestation of participants' increased comfort and ease with handling money, from the point of view of those who advocate greater access to finance, is when participants choose to borrow to expand their activities or start new enterprises.

But are they graduating?

* Although the Ford Foundation and CGAP launched their own Graduation Program in 2006 to test whether the BRAC model could be successfully adapted outside Bangladesh (resulting in 10 pilot programmes implemented across eight countries that recently reported back very encouraging findings, on which more later), BRAC's own CFPR-TUP remains the most intensively studied of all the graduation models implemented so far, with three rounds of surveys conducted so far on the same group of participants since 2002. They show:

* 95% of participants graduated through fulfilling six of the nine graduation indicators.

* 92% had moved above the half-a-dollar a day threshold

* Chronic food insecurity fell by 47%; annual food expenditure rose by 93%; caloric intake increased by over 22%.

* Spending on medical treatment increased; sanitary conditions also improved; a majority of participants use latrines.

* 83% of selected households felt more confident about coping with crises and accessing resources from their communities.

* Participants save more than non-participants. The number of participants with outstanding loans increased from 27% at baseline to 77% one year after the end of the programme, indicating greater access to finance, as well as participants availing this access.

Additionally, a recent independent study carried out by Robin Burgess of the LSE along with academics from London and Milan found that the scheme led to a 35% increase in people's incomes after two years.

Results from some of the 10 pilots supported by the Ford Foundation and CGAP (with local NGOs as implementing agencies) in Haiti, India, Pakistan, Honduras, Peru, Yemen, Ghana and Ethiopia reported findings recently at a conference in Paris, and it's only fair to say they exceeded expectations. The findings from five years of randomised control trials evaluating the impact of the model showed that across countries, participants typically improved their food security, stabilised and diversified their incomes and increased their assets.

The results are all strong evidence that the graduation model can work. In Esther Duflo's words, "These are very, very good, results. [...] I don't think you could have ever expected anything better." And as noted by Dean Karlan of Yale University, one of the researchers who presented the findings, perhaps the most heartening of all the results that were presented was that in the two sites where “happiness” was measured -- Honduras and West Bengal -- it was shown to have gone up.

SUMON YOUSUF/BRAC

SUMON YOUSUF/BRAC

That may or may not come across as some fluff data to you, especially since it has to do with such an intangible indicator as happiness. But when donors, who are often the ones financing these initiatives, start recommending such programmes involving the direct transfer of cash or assets -- something that goes against BRAC's own long-established “help yourself” approach to development -- you know you better start taking notice. The UK's National Audit Office, a government watchdog that monitors spending by DfID, in a report released last year said that DfID's spending on programmes including some form of direct transfer of assets showed “clear immediate benefits, including reduced hunger and raised incomes”.

While admitting that funding for such social protection programmes remained “problematic” for donors, DfID is gaining greater assurance that aggregate programme benefits outweigh the costs, demonstrating “important characteristics of good value for money”. The report by the NAO was followed by one from a parliamentary committee earlier this year expressing surprise that the use of direct transfer programmes had not increased more “in light of the evidence of positive outcomes”.

BRAC's experience, however, has taught it only too well about the multi-faceted manifestations of poverty for it to now regard the graduation model as the panacea it always knew microfinance wasn't. BRAC knows not everyone will graduate out of its CFPR-TUP programme, and that success ultimately depends on a number of external factors as well, such as market conditions that the model can't control. Most of the pilots are very small in terms of their scale and coverage. Scaling up to make a substantial difference will require state support. But the fact that it is especially targeted at a heretofore forgotten segment of the population, and is slowly starting to work for them by making them visible, by just bringing them into the fold, is cause enough for hope. And a little bit of hope can carry these people a long, long way.

Shayan S. Khan is Knowledge Management & Strategic Communications Specialist at BRAC.