Inside

Original Forum |

| Truth, a Casualty of War -- Irfan Chowdhury |

| On the Notion of Tolerance -- Shakil Ahmed |

| Violence -- Reversing the culture of impunity -- Manzoor Ahmed |

| Lessons from the Troika of Non-Violence: Gandhi, King and Mandela -- Ziauddin Choudhury |

Institution-Building or Rebuilding Institution? Focus on Bangladesh -- Dr. Mizanur Rahman Shelley |

Rethinking 'The Fear' --- Tapas Kanti Baul and Sultan Mahmud Ripon |

No Respite for Rohingyas |

Politics Not for the People -- Syed Ashfaqul Haque |

Marriages: Made in Heaven, Living Hell for Many -- Aruna Kashyap |

| Fighting a Lone Battle -- Naimul Karim |

| The Story of the Rise of Modern China -- Ashfaqur Rahman |

| Che: The legacy endures -- Syed Badrul Ahsan |

| Graduating Out of Exclusion -- Shayan S. Khan |

| The Dream Team --Megasthenes |

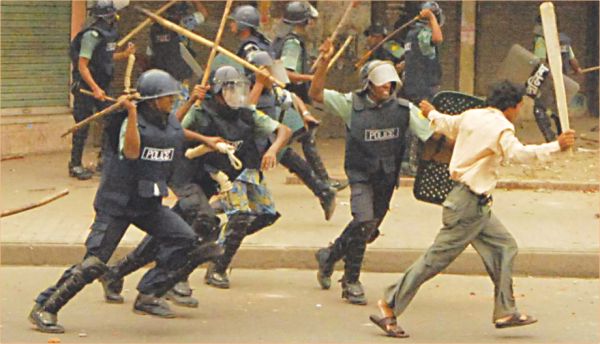

Violence -- Reversing the culture of impunity

Only a multi-faceted political, legal, social and communications approach can cure the syndrome, argues MANZOOR AHMED.

Aminul Islam, a labour organiser among garment workers in Ashulia, west of Dhaka, disappeared on April 4, 2012. Days later, police found his body dumped on the roadside, bearing marks of brutal torture. The garment workers of Ashulia worked in factories which produced readymade clothes for international brands like Gap, Tommy Hilfiger and American Eagle. But the workers remained poor and exploited and they came with their problems to Aminul about unpaid wages, abusive bosses and denied maternity leave. Aminul and his organisation attempted to address the workers' complaints by mediating with factory managers and authorities. Improbably, with no identification and claimant for the body, Aminul was quickly buried in a pauper's grave. Only when a newspaper published a photo of unidentified Aminul, his family in the village of Hijolhati, an hour's drive from Ashulia, came to know of his fate. The killing involving the high stake garment export business drew international attention. International labour unions and diplomats, including the US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton protested. However, five months later, the killing remains under investigation, no arrest has been made, and police cannot report any progress in the case.

Star Photo

Star Photo

***

Limon Hussain, a 16-year-old college student from village Saturia under Rajapur police station in Jhalakati district, as he walked, unarmed, near his home with a friend, was shot by the Rapid Action Battalion team in March 2011 at point-blank range, maiming his left leg. The leg had to be amputated to save Limon's life. RAB accused him of being involved with a terrorist gang. However, RAB's Director, Mokhlesur Rahman, on April 11 last year said Limon was the victim of a 'shootout' between RAB and criminals. Yet, police and RAB investigation led to framing charges against Limon as a terrorist. Human rights lawyers and activists are sceptical of the charges which, according to them, are short of specific credible evidence.

On August 20, 2012, Ibrahim Hawlader, known to be an 'informer' of RAB, physically attacked Limon and his mother, while they waited for a bus near their village. Both required treatment at the local hospital. It is 18 months since the fateful afternoon when Limon was shot by RAB, because he was at the wrong place at the wrong time. The cases by police and RAB against Limon on charges of having terrorist links and obstructing justice remain under trial. A hearing date was set for September 26, 2012 at the court of Senior Judicial Magistrate Nusrat Jahan in Jhalakati.

***

Fourteen-year-old Hena Akhter was assaulted and raped by her cousin and neighbour Mahbub on a January night in 2011, as she came out of her house to relieve herself. Her scream brought Shilpa, wife of Mahbub to the scene, but instead of bringing Hena to her family, Shilpa joined her husband and brother in beating up Hena. Hena's father eventually rescued her. The lmam of the village mosque issued a fatwa that both Hena and Mahbub should receive a hundred lashes for their sinful act. After 60 lashes, the already ill and injured girl fainted. Her family hesitated to seek medical help out of shame and pressure from neighbours not to make a fuss about it. When Hena's condition became critical, she was taken to the health centre several days later. After five days in the hospital, Hena died on January 31. Newspaper reports attracted the attention of the High Court and a suo moto ruling was issued to exhume the dead girls' body, have a post-mortem done and file charges against the assailants.

***

An Amnesty International (AI) report comments on the major role that student groups play in human rights abuses and political violence:

When in opposition, Bangladeshi political parties have often expressed their concern about human rights violations inflicted on their members. Such violations have included: arbitrary arrests at the instigation of the ruling party officials; use of the police force to torture or ill-treat members of opposition parties; and the filing of politically motivated criminal charges against opponents.

However, the same political parties have often remained silent in relation to human rights abuses reportedly carried out by their own members.

Abuses by political parties have usually been carried out by the “student” wings of the major parties... When their parties are in government, such “student” groups, who reportedly keep and use fire arms, can become unchallenged perpetrators of human rights abuses reportedly under the patronage of their party leaders. The involvement of such armed “student” and other groups in the political process is believed to be one of the major causes of continued high levels of political violence, including patterns of killings and serious injury in Bangladesh. Political parties have pledged, but failed, to disarm their own “student” groups. (Amnesty International 2006, Bangladesh: Briefing to political parties for a human rights agenda, ASA 13/012/2006, October, pp.2-3.)

***

The vignettes based on media reports presented above show the many facets of violence that have gripped our society today. Are they all stray and scattered phenomena unrelated to each other which affect directly only a tiny proportion of the population? If so, we don't need to be overly concerned about these events, do we? This would be the pat response of politicians in power -- a pattern of explanation used by them whenever they are confronted with uncomfortable questions from the public. The same formula is applied, whether this is about prevalence of crime and violence, corruption in public office, dangerous chemicals in fruits and vegetable, or safety standards of river-plying passenger launches.

The phenomena described above are all characterised by a degree of violence and criminality which should be unacceptable even if they were scattered events. But it is not necessary to scratch far beyond the surface to uncover a thread that binds them together.

The violent behaviour pattern evident in all the situations are aided, abetted and tolerated by a nexus of short-sighted patronisation politics, corruption and greed, and incompetence and absence of public accountability, all of which support and feed on each other. Moreover, any one with eyes and ears open will readily agree that the vignettes indeed represent a much wider pattern spread across our society affecting most citizens in one or another way. They have collectively contributed to creating a culture of impunity. These phenomena threaten to hold the future of the nation hostage, if not brought under control.

The birth of Bangladesh in the anvil of violence on a genocidal scale forced upon the people by a brutal enemy and the compulsion of resistance and fighting back shattered the romantic imagery of the Bengalis as a gentle and tolerant people who loved music and poetry and nourished a culture of tolerance across religions, ethnicity and socio-economic differences. Then the struggle to establish a democratic, liberal and progressive polity in the newly born nation was derailed violently when the founder of the nation was killed by elements of the armed forces in August 1975. A legacy of impunity was created when the killers were allowed to go free by those who captured state power. The same forces discouraged a reckoning of violent crimes committed against the people by local collaborators of the enemy during the liberation war. Instead, the alleged perpetrators of crime were helped to be rehabilitated and brought into a political coalition which ruled the country intermittently since 1975.

It took three decades and toppling of the autocratic military regime by popular uprising in 1990 for the killers of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to be brought to trial and punished. A fledgling start has been made after four decades since liberation to bring under trial the alleged offenders in “crimes against humanity” during the liberation war.

Many other cases of egregious criminal violence remain unresolved. Among these are the murder by military personnel of national leaders while in jail custody during the 1975 coup, bomb blast in Jessore in 1999 against the cultural troupe Udichi that killed 10 and injured 200; explosion at the Bengali new year celebration on April 14, 2001 at Ramna, killing 10 and injuring over a hundred; the grenade attack at a Awami League political rally on August 21, 2004 that killed 24 and hurt over 500; and killing and maiming of journalists in all parts of the country. A phenomenon that has gained notoriety as a new form of violence is forced disappearance, popularly known as gum, allegedly by law enforcing agencies or with their connivance, when an adversary has to be punished or eliminated. This recent national history littered with high profile violence cannot be ignored in considering prevalence of violence and ways of coping with it.

Without attempting a scientific taxonomy, common manifestations of violence can be put under several broad categories, though these are not altogether mutually exclusive. The suggested categories are marked by somewhat distinct cause and effect chains. These principal categories, not necessarily in any order of their incidence and severity, include violence arising from or related to: electoral politics, gender values and attitudes, student politics, religious fanaticism, vigilantism, illicit drugs, and breakdown of law enforcement and judicial systems.

Electoral politics. Analysis by civil society bodies like Shujan and others of people drawn to electoral candidacy, the selection of candidates by parties, election campaign and subsequent behaviour no matter who is elected -- shows flagrant supremacy of “money and muscle”. Electoral reforms, including framing and enforcing rules about representation in public offices, have been half-hearted about changing the election process to eliminate the influence of money and muscle power. Even the rules that exist are not enforced fully because it requires interest and commitment of the major political parties.

Star Photo

Star Photo

It is a common practice for many seekers of elected public offices to maintain their own cadre of musclemen or mastaans whose job description requires them not to have much regard for the niceties of law and democratic values. The need for nurturing their own loyal “enforcers” apparently prevents major political parties from cutting loose their student wings. The mindset of the majority of political leaders apparently is such that they are not ready to ask themselves whether the extortionist and highhanded conduct of loyal supporters is actually a liability and abandoning them would be a potential boon.

Violence against women. United Nations says, “violence against women shall be understood to encompass, but not limited to, physical, sexual, and psychological violence perpetrated by family members, the community, or the state (UN, Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women, 1993).

The common manifestations of violence against women in Bangladesh take different forms.

Domestic violence, or violence perpetrated at home and in the family, is a major social problem in Bangladesh, to which women of all economic strata are vulnerable. Nearly half of the adult women are physically abused by their husbands, according to a survey. Greed and commercialisation of marriage have prompted dowry-related violence and even “dowry-killing”. Incidence of rape or physical violation of women, particularly injurious to a woman's self-esteem and her physical and psychological well-being, apparently is rising.

Trafficking of women and children is a serious problem in many developing countries including Bangladesh. In the absence of social protection, economic security and legal support, porous border with India and apparently a growing market, women and children from the poor and marginalised sections of the community become easy victims of trafficking.

Acid violence is a particularly cruel act, mostly against young women, that has grown in number of incidence. It is a form of misogyny that involves flinging of acid on the bodies and faces of women as an act of revenge. Bangladesh has the dubious distinction of highest incidence of acid violence in the world.

Victimisation of women by fatwa, a religious edict considered to be based on Shariah law, often puts women's life in danger, as illustrated by the case of Hena. Illegal according to national law, it is often tolerated or abetted by community leaders, politicians and law enforcers.

The diverse forms violence against women take have been an obstacle to compiling comprehensive statistics of incidences and trends. The problem is not insurmountable if all possible sources are reached out to, including court and police records as well as hospitals and newspapers, complemented by civil society organisation sources. A database is essential to carry out a serious assault on this scourge.

Campus violence. Violence that has engulfed educational institutions jeopardises life and limbs of students and threatens their educational achievement. Perhaps more importantly, it is an incubator of the disease that would multiply and perpetuate in the future through the students coming out of the educational institutions well-versed in the culture of violence. As the Amnesty report suggests, the problem is nurtured almost entirely by the political modalities and can be solved only if and when better sense prevails among the political class. Civil society and citizens have to work on making the prevailing behaviour pattern costly for politicians.

Religion-based violence. Religious fanaticism mixed with diverse political, economic and cultural grievances has spawned violence worldwide. Authoritarian military regimes in Bangladesh, seeking legitimacy and popularity, exploited popular sentiment and trifled with political and constitutional foundations built after liberation. Fifteen years of military rule and its legacy continue to haunt the country as it struggles to return to its secular and progressive roots. The risks of religion-based violence have not abated, which demand a watchful approach.

Other diverse vectors of violence, such as, vigilantism, illicit drugs, settling disputes outside the law by intimidation, and breakdown of law enforcement and judicial systems, reflect a general failure of governance. Technical solutions for each of these problem areas can be designed and indeed some initiatives are underway with the support of UN agencies and donors and by NGOs. These, however, can have a sufficient impact to reverse the downward slide only when the political will can be generated not to condone, tolerate, and indeed encourage, aberrant behaviour.

What can be done?

The culture of impunity must be checked and reversed. Major institutions of our society have to recognise the seriousness and urgency of the malaise and find ways of focusing their effort on remedial measures. Law enforcement, judiciary, education, communications media and community activism have to play their role to halt and reverse the culture of impunity about violence. The society-wide effort has to be promoted and supported by the political process.

Law enforcement and judiciary -- police, courts, prosecution system, enforcement of verdicts -- remain the sources of problems and have to be turned into solutions. Police reforms and capacity-building must incorporate, among other measures, an effective non-politicised civilian review mechanism of police effectiveness and accountability at local, district and national levels. This approach has been found helpful in many countries. Judiciary from the apex courts to local ones must subject themselves to systematic self-assessment about how the system responds to critical social concerns including violent crime. This can be done under the auspices of the Supreme Judicial Council, a body with a mandate to uphold the independence and integrity of the judicial system. A particularly egregious problem is the criteria and application of bail terms to perpetrators of violence, who in far too many instances manage to be freed on bail and can engage in violence and intimidation while on bail.

The symbolism as well as practical results will be invaluable if a semblance of order and peace can be restored to educational institutions in the country. A political choice has to be made, led by the regime in power and, mobilising the support of citizenry at large, to leave students, teachers and the education system management out of short-term political calculation and factional rivalries. Actually, such an initiative can be turned into a political capital by those who would pursue it seriously and convincingly.

Communications -- electronic and print media and, increasingly, the internet and social media -- need to be harnessed to raise awareness and empower people to defend themselves. This effort has to be linked up with various political and institutional initiatives. It is at the individual and community level that the impact of violence is most directly felt and trust has to be built among all actors in the community for active engagement in changing the culture of violence and impunity (World Bank, Violence in the City: Understanding and Supporting Community Responses to Urban Violence, 2011) Resistance has to be built at the community level with communications in various forms as a strong ally.

Manzoor Ahmed is Senior Adviser, Institute of Educational Development, BRAC University.