| |

The Samaritan Healer

Kajalie Shehreen Islam

Most people do not know the Hippocratic Oath by heart, but what they do expect from their doctors is dedication and compassion. In our fast-paced and increasingly materialistic world today, these and a host of other qualities expected in doctors often come at a rather high price, if at all. Dr. Abdul Quader is an exception to the norm. Though relatively few people know of him, those who truly need him find their way to him from far and wide, and once they do, they are never disappointed.

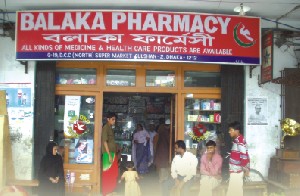

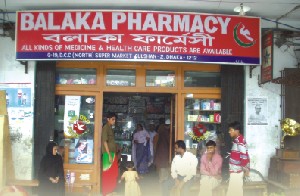

On

any weekday morning, the Gulshan 2 market, usually frequented

by the rich of the area, can be seen crowded with all

kinds of poor from all over the city. The Balaka Pharmacy

becomes a temporary haven for the underprivileged who

seek the unconditional help of Dr. Abdul Quader.

Ram

Shona works as a domestic help in Kathaliya, Badda.

When her three-year-old son Joy's eyes grew yellow and

he wouldn't eat properly, she brought him to Dr. Quader.

“I've been coming to him for years,” she says, “from

even before I was married. He is very good.”

Mohammed Tayebur Rahman, a carpenter, has also been

consulting Dr. Quader for over twenty years. “I come

all the way from the Cantonment,” he says. “I've taken

medicine from elsewhere, but this is where I have always

been healed. The doctor has a good name and he is very

good in his work.”

Dr.

Quader established the Balaka Pharmacy and his own small

chamber in a corner of the Gulshan 2 market in 1974.

“I had wanted to help the poor from when I was a student,”

he says, “and when I opened my own pharmacy and chamber,

I put up a sign on the very first day saying I would

see poor patients free of charge.”

Gulshan

at the time was not as huge as it is today, but patients

from many nearby areas came to see him and they still

do. “Drivers, rickshaw-pullers and all kinds of people

working and living nearby come here,” says Humayun Kabir,

an employee of the Balaka Pharmacy for the past eighteen

years. “We have patients coming to us from as far off

as Badda, Tongi, Norshingdi, Munshiganj and even Mymensingh,”

he says. “They crowd at the door even before it is open

early in the morning.”

Dr.

Quader's father, Abdur Razzak, was a landlord in Norshingdi.

His mother, Ayesha Akhter, a 'Minor Pass', equivalent

to Class 6, in the 1920's -- which was very rare for

women at the time -- encouraged him and his brothers

to pursue their studies. “My mother always wanted one

of her sons to be a doctor,” recalls Dr. Quader, “one

an engineer and one a professor. That is exactly how

it is,” he says happily.

“I

myself remember wanting to be a doctor from when I was

in Class 9,” says the 70-year-old General Physician.

He had contracted typhoid at the time. “The nearest

MBBS doctor was five miles away from where we lived,”

he recalls. “Though he advised my parents as to how

to treat me, he wouldn't come over and see me himself.

I recovered but I lost a lot of weight and was very

broken down by the ailment. It was then that I decided

to become a doctor, available to everyone.”

Dr.

Quader completed his LMF (Licensing of Medical Faculty)

and later, in 1972, his MBBS from Dhaka Medical School.

He had worked at a government job for a while prior

to that, and during the Liberation War, practiced in

Shivpur. He recollects the difficulty in maintaining

neutrality during the war. “The Pakistani army and the

Mukti Bahini would each accuse me of being on the other's

side. I only tried to heal any wounded who came to me.”

Dr.

Quader has no fixed rates. While foreigners and local,

more “solvent” parties pay relatively more, the poor

and underprivileged remain the majority of his patients.

They pay whatever they can, from Tk. 50 to Tk. 10 to

nothing at all. The wife of a trawler operator and herself

a domestic worker, Ram Shona cannot afford to pay much.

“The doctor takes whatever we give him,” she says. “Sometimes

I pay Tk. 20, sometimes, Tk. 30.” Those who can pay

nothing are given free medicine or the money to buy

medicine by the doctor.

The

poor aren't his only patients, however. “I started consulting

Dr. Quader in 1985,” says M. Aminul Islam, a retired

Secretary and Ambassador. “I found him to be very patient

and an attentive listener to his patients' problems.

He only suggests medicine that you really need to be

cured. For example, he won't prescribe strong antibiotics

for coughs and colds that would heal anyway. I received

results from his treatment which is why I often consult

him when unwell. He is so experienced that sometimes

he can just tell what's wrong without doing extensive

tests. And when I learnt of his services to the poor,

I knew that he was not only a good doctor but also a

very good man.”

The

doctor sees around fifty to sixty patients a day and

does not have rigid visitation hours. Though his business

card claims his office hours to be from 8 a.m. to 12

p.m., if there are patients to attend to, he stays well

beyond noon, and the patients keep pouring in. Helal,

an employee at the Balaka Pharmacy says, “The doctor

will only leave after the last patient does. If a patient

shows up even when the doctor is at the door on his

way home, he will turn back and see him. He never says

no to a patient, and often ends up leaving at 3 or 4

in the afternoon.”

“He

is one of a kind,” adds employee Humayun Kabir affectionately.

In

a time where most doctors are some of the richest people

in the city and who do not hesitate to charge unreasonably

high visitation fees for 5-minute consultations, how

does Dr. Quader afford to run his chamber and pharmacy

as well as to invest so much time and energy?

Maintaining

the establishment is not a hardship, he says. “Instead

of distributing clothes among the poor, I invest all

the money I need to pay as zakaat in my poor patients.

I even have a considerably large poor fund from which

I help pay for patients' medical tests and operations.”

As

for medicine, many doctors get free samples from the

various pharmaceutical companies. “I get almost Tk.

10,000 worth of sample medicine from the various companies,”

he says, pointing to some drawers in his desk filled

with medicine. “I give these for free to the poor and

some to the Central Dispensary.” Most other doctors

sell it off.

The

Balaka Pharmacy also sells medicine at the price at

which they buy it from the companies. So while other

pharmacies sell medicine originally worth Tk. 10 for

Tk. 12, buyers at Balaka get it for less. “The companies

also make huge profits,” says Dr. Quader, “and claim

to give it to charity which they very well might, I

don't know. But I give directly to those who come to

me in need.”

“A

60-year-old widow came to me today,” says Dr. Quader.

“Her only son won't let her live with him and she has

no place to stay. When she fell sick, he gave her 50

Taka and sent her to me. Another patient had arthritic

pain and I suggested she not do unnecessary tests, but

she was adamant. The results were as I thought -- osteoporosis.

She did not have the Tk. 350 that was due. Women and

children are the majority of my patients,” he says,

“as they are, in effect, the poorest. Mostly they suffer

from malnutrition, gradually resulting in a variety

of ailments from diarrhoea and pneumonia to allergies,

bronchitis, asthma and rheumatics. If necessary, I refer

them further to doctors and specialists, the ones they

can afford.”

Are

there other doctors like him in the city? Dr. Quader

smiles at the question. “I am not special,” he says.

“I am not any different from the others. Only, money

is not my prime concern.” A novelty indeed in today's

world.

“Some

poor patients tuck a note into my hand,” says the physician,

“and after they leave I see it is 10 Taka. I don't mind.

I even pay for operations if they are not minor operations

that I can do for free,” he says.

Before everything became so specialised,

Dr. Quader performed minor surgery. Today, he supervises

operations. But when a poor woman on her way to a wedding

has her earring snatched and her ear lobe torn, or a

poor man has a nail or a thorn and fear of infection

in his foot, Dr. Quader stitches the wounds.

When it comes to major surgery, he refers

them to Dr. Chowdhury Habibur Rahman, recently retired

from the Holy Family Hospital, says Dr. Quader. Dr.

Rahman does operations for much less than the usual

rates, if not for free, and Dr. Quader fills in the

rest from his poor fund for patients who cannot afford

them.

There are, of course, some problems

the doctor faces. “On principle,” he says, “I never

give false certificates. There are people, even secretaries

and ministers who perhaps do not want to appear in court,

for example, who request them, and, though I still refuse

them, I am put on the spot.”

“Other prominent people, as well as

local thugs, break the queues to see me, sometimes causing

a havoc at the pharmacy.”

Before, Dr. Quader used to go on house

calls to see patients. Now, however, he only goes to

families of whom he is family physician, in and around

Gulshan, Banani and Baridhara. “Some people who are

well enough to come to my chamber ask me to go see them,”

he says, “when I have patients who need to be attended

to at the pharmacy. Going on house calls has also become

risky. Sometimes you are given addresses that are not

even houses, and when you go there, they'll point a

gun to your head and strip you of any valuables you

may have on you.”

In countries abroad, each area has its

own family physician, says the doctor. “We have set

up a similar Academia of Family Physicians here.” Dr.

Quader believes this is very important. “Many families

need not only medical treatment,” he says, “but also

emotional advice.” There are problems between parents

and children and so on, the physician has noticed, which

later lead to health problems, such as heart ailments

and high blood pressure from extensive worrying. “These

families often need emotional counselling rather than

medical help to get things into perspective and themselves

correct what cannot be done medically,” says Dr. Quader.

espite having helped the poor so generously

over so many years, Dr. Quader does not have to live

frugally and he does not complain about the difficulty

of making ends meet. He lives in one of his own set

of apartments in Nikunja, and associates with people

from all walks of life. “I have always maintained a

simple, middle-class lifestyle,” he says, “so that anyone

at all can come to me, from ministers and secretaries

to rickshaw-pullers and domestic workers.”

He has definitely succeeded. The Balaka

Pharmacy is crowded with patients from all social classes

though the needy make up the majority. They feel at

ease with the soft-spoken, compassionate doctor, willing

to listen, and trying to heal to the best of his ability.

His son, Dr. Lutful Karim, a chest specialist,

also sees patients at Balaka in the afternoons and evenings.

“I hope my son will be able to go by the ethics I have

tried to maintain,” says Dr. Quader. His daughter-in-law

and two sons-in-law are also doctors.

“Most

doctors today take up medicine with the objective of

making money,” he says. Dr. Quader's only message for

young doctors today, as well as his suggestion for setting

up medical facilities for the poor, is to be humane."

Many doctors,” he says, “will prescribe

a number of unnecessary tests, and get a 40 to 50 percent

margin of the profits at the end of the month.” We do

not have enough doctors, medicine and medical facilities,

he believes, but if we could make honest use of those

we do have, health care in this country would not be

in such a miserable state. Unfortunately, we are extremely

corrupt. The medicine, gauze and bandages are often

missing from hospitals also, stolen by the nurses themselves,

he says.

“Money isn't everything,” says Dr. Quader.

“Humanity is. I don't ask doctors to do charity work.

But if each of them would at least see 20 or 25 percent

of poor patients for free or nominal fees, it would

make life much easier and better for many of the poor

in our country.”

Like everything else in our world today,

medical treatment and healing have become expensive,

sometimes even exploitative, commodities. It is difficult

to find doctors like Dr. Quader who will take the time

to listen to a patient's problems and suggest remedies

that will actually work, while at the same time considering

whether the patient can or cannot afford to pay the

doctor's fees. It is even more rare to find a doctor

who will expect and accept even nothing in return.

“I don't have hordes of money, but I

am very satisfied with my life,” says the doctor, also

a proud grandfather of thirteen. “I am comfortable,

I am happy. I don't need a high life. I spend my free

time praying at the mosque and playing with my grandchildren.”

Photos by: Zahedul I. Khan and Imran

H. Khan

|

|