|

Cover

Story

The

Death of

Dhaka's

Posh Spots

Kajalie Shehreen Islam

Every

city has its posh residential areas. Away from the bustling

city, quiet and serene, these are where the well-off dwell,

and where others drive by, dreaming of buying a house there

someday. Once upon a time, Dhaka too could boast of elegant,

quiet residential areas where cosy or majestic houses with

fragrant flower gardens lined the tranquil lanes adorned with

billowing trees. Every

city has its posh residential areas. Away from the bustling

city, quiet and serene, these are where the well-off dwell,

and where others drive by, dreaming of buying a house there

someday. Once upon a time, Dhaka too could boast of elegant,

quiet residential areas where cosy or majestic houses with

fragrant flower gardens lined the tranquil lanes adorned with

billowing trees.

That certainly

is a far cry from residential neighbourhoods of today's Dhaka.

Its so-called "posh", "residential" areas

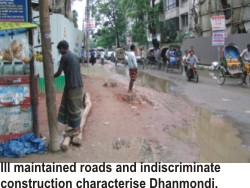

have and continue to become anything but that. Dhanmondi,

Gulshan, Banani, Baridhara -- places where half the city travels

to every morning, to work in banks and restaurants, shops

and garment factories.

Quaint

independent houses have been turned to high rise apartment

buildings, sacrificing the beautiful gardens. Lanes are now

thoroughfares where cars honk rudely and create traffic jams.

Roads are pot-holed, muddy and smell of rotting garbage left

in heaps in corners. Avenues of elegance have been turned

into lines of commercial establishments from banks to schools

to clinics. So what happened to the best neighbourhoods of

Dhaka?

Decadent

Dhanmondi

Even in the early '80s, Dhanmondi was a picture perfect residential

area with independent homes, lakes, and only a few corner

shops. Today, people sometimes forget that Dhanmondi R/A actually

stands for Dhanmondi Residential Area -- even those who live

there. "It's a commercial area," insists Khurram

Kabir. Offices and shops, schools and hospitals -- it is anything

but residential.

"The

road I live on in Dhanmondi," says Mahmood Ali Noor,

a student of IUB, "is one of the most crowded, busiest

and dirtiest. But it will fulfil all your needs," he

says very matter-of-factly.

When

giving birth to children (or for anyone ill), says Mahmood,

there are two hospitals and two diagnostic centres on his

street. Once the children are old enough to go to school,

there are seven English medium schools to choose from -- on

that very street. ("I wake up to the national anthem

every morning!" he says.) There are coaching centres,

colleges and two universities. And when the children grow

up and are ready to get married, no problem, because there

are also two community centres right there. Not to mention

the variety of apartments the newly-weds can choose from.

"All we need now is a cemetery here," he says simply. When

giving birth to children (or for anyone ill), says Mahmood,

there are two hospitals and two diagnostic centres on his

street. Once the children are old enough to go to school,

there are seven English medium schools to choose from -- on

that very street. ("I wake up to the national anthem

every morning!" he says.) There are coaching centres,

colleges and two universities. And when the children grow

up and are ready to get married, no problem, because there

are also two community centres right there. Not to mention

the variety of apartments the newly-weds can choose from.

"All we need now is a cemetery here," he says simply.

There

are only five independent houses on his street, says Mahmood;

the rest are all apartments. Plots in which one family used

to reside now house 24.

Dhanmondi

has around 20 of the total of about 64 private universities.

Offices of political parties also cause problems, not to mention

the big markets and plazas on every main street.

"I

can't go for a late-night walk on my own street without seeing

several prostitutes being picked up by people in passing cars,"

he adds.

It is

not all bad, however. The renovated Dhanmondi Lake has become

a popular hangout for many. The boating club, fishing club

and two sports fields also contribute to the entertainment

scenario. But, this bit of Dhanmondi that has not become mercilessly

commercial, has become recreational, and not only for its

residents but the whole city. Which leaves little peace for

the residents living around the area. Residents in fact have

little say in the residential areas.

Brokedown

Banani

The broken

roads of Banani is the foremost grievance of resident Sameer

Ahmed, visiting from the US. It takes all the powers of his

digestive system to get home intact after a filling lunch

on a rainy day. But he usually survives the grievous bumps

and puddles and even the lidless manholes. "You would

know how bad it is if you drove to my house," he complains. The broken

roads of Banani is the foremost grievance of resident Sameer

Ahmed, visiting from the US. It takes all the powers of his

digestive system to get home intact after a filling lunch

on a rainy day. But he usually survives the grievous bumps

and puddles and even the lidless manholes. "You would

know how bad it is if you drove to my house," he complains.

While

broken roads and dangling wires do not do anything to add

to the beauty of the area, they also make it unsafe for people

to be out on the street. Those who can help it do not even

walk in front of their own homes.

"There's

a huge garbage dump right in front of my house," complains

Tanzila Zaman, who lives just across from the field of a festive

cattle market before Eid-ul-Azha. "It's supposed to be

near the bazaar, but that's close to the homes of some influential

people which is why it is randomly dumped in front of mine."

"There

are no street lights here," adds her sister, Tasrina,

"and there used to be a big slum."

The slum

dwellers had their own businesses inside the shanties, selling

drugs and alcohol to elite buyers. Many of them have been

evicted, though some shanties still spring up in empty plots

of land while most are confined to one colony. Today, the

Zamans' next-door neighbours are a private university on one

side and a small shopping complex behind.

Grimy

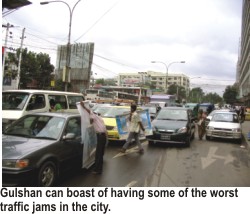

Gulshan Grimy

Gulshan

Forty years ago, houses in Gulshan (meaning garden) were at

least half a mile apart. Thirty years ago, people used to

go there to practice driving because a passing car could only

be seen every five or six minutes. Today, even during hartals

the roads are busy. Shops and clubs, schools and garment factories,

banks, restaurants and high-rise buildings are what today's

Gulshan is all about. Few independent houses remain, and even

their owners are beginning to tire of the area.

"Gulshan

is not a residential area anymore," is the common complaint

of its inhabitants.

"It's

all shopping and banking and flats and restaurants,"

says Naina Karim, who grew up there as a child and returns

every year to visit her parents who still live there. "Which

isn't all bad, because it is sort of convenient to get things

done, but it's just too commercial."

"And

even within Gulshan, it takes forever to get anywhere,"

she continues, "not to mention anywhere else in the city!

It's too congested, and even rickshaws aren't allowed in many

parts now when they actually helped to get around." Naina

remembers being able to walk down the road in front of her

house and down to the park nearby. "Now, even that's

not possible," she says.

"Gulshan

is highly overrated," thinks Rayan Ahmed, a resident

of a flat in the area. "It's full of slums. Security

guards are always loitering around annoyingly. And the dangling

wires are only the visible side of the electricity problems

there."

Local

clubs and private schools in Gulshan contribute to the already

hectic traffic with people never following any rules while

driving and parking haphazardly everywhere. Guesthouses have

sprung up in many parts of both Gulshan and Banani. These,

along with the big markets, rent out their lucrative ground

floors as reception areas and shops, having no regard for

parking spaces to ease the traffic. Local

clubs and private schools in Gulshan contribute to the already

hectic traffic with people never following any rules while

driving and parking haphazardly everywhere. Guesthouses have

sprung up in many parts of both Gulshan and Banani. These,

along with the big markets, rent out their lucrative ground

floors as reception areas and shops, having no regard for

parking spaces to ease the traffic.

There

is no point in barring rickshaws, says Rayan, as people who

need to get anywhere just bribe their way through. According

to him, the rules are not strict enough and the traffic is

no better. To add to that is the new Gulshan circles-turned-signals.

While people are still waiting to see how they have helped

the traffic situation in the area, Rayan says it is the "worst

decision anyone could have made".

The biggest

tragedy of Gulshan is its disappearing lakes. Even in the

'80s, there were lakes all around Gulshan and lake view houses

were the most envied of locations. But over the years the

lakes have been filled in with high rises indiscriminately

encroaching the water bodies.

Gulshan

also seems to have more than its share of Dhaka's mosquitoes,

think many of its inhabitants. Residents moreover complain

about sex workers lined up in front of their apartment buildings

late at night. Another common Gulshan scenario, especially

during the rainy season, are the flooded roads. Shanties are

next-door neighbours to posh independent houses, and garbage

lies around on every street. Rush hour traffic, besides school

closing times, include the lunch hours of garment workers

employed in large factory buildings throughout the area. So

much for the "diplomatic zone"! Gulshan

also seems to have more than its share of Dhaka's mosquitoes,

think many of its inhabitants. Residents moreover complain

about sex workers lined up in front of their apartment buildings

late at night. Another common Gulshan scenario, especially

during the rainy season, are the flooded roads. Shanties are

next-door neighbours to posh independent houses, and garbage

lies around on every street. Rush hour traffic, besides school

closing times, include the lunch hours of garment workers

employed in large factory buildings throughout the area. So

much for the "diplomatic zone"!

Soon-to-be

Bustling Baridhara

And so the "diplomatic zone" gradually moves to

Baridhara.

Baridhara

is, so far, relatively more peaceful, cleaner, and more "residential".

Now that is where many embassies are and where the affluent

choose to have their homes. But even here is the common problem

of traffic congestion.

"It

takes a long time to get places," says Sonia Rahman,

a resident of New DOHS Baridhara. "And you can't always

get transport because empty rickshaws and CNG scooters aren't

allowed in the area."

"There's

not enough space to really do anything here either,"

says Sonia. "It's already congested. But even then, a

big mall is being built."

And so

it begins. Is history repeating itself?

A

Roadmap to Nowhere

Mustafa

Zaman

The

Rajuk Master Plan defines the well-planned residential areas

as 'development areas' and the rest as 'spontaneous growth

areas'. Kamal Ahmed, a graduate from the Institute of Fine-Arts,

Dhaka University, is the second youngest son of his family

that had a plan to build a house of their own in a third zone

'a private development area', which is Adabor. The family

inherited a small patch of land from the deceased father and

managed to save some money sent by Kamal's two brothers living

in the Middle East. Around the year 2000, they thought the

dream to have a house of their own would soon be a reality.

But it took Kamal, the sibling in charge of building the dream

house, two long years to get the plan through Rajuk. The plan

first got caught in the official procedural web and was later

faced with regulatory barrier as by then a new rule was introduced

that required a 12 foot wide entry path for any house. The

house that Kamal was set to build the entry road measured

only 8.33 feet in width, and it was in accordance with the

rule during submission. The

Rajuk Master Plan defines the well-planned residential areas

as 'development areas' and the rest as 'spontaneous growth

areas'. Kamal Ahmed, a graduate from the Institute of Fine-Arts,

Dhaka University, is the second youngest son of his family

that had a plan to build a house of their own in a third zone

'a private development area', which is Adabor. The family

inherited a small patch of land from the deceased father and

managed to save some money sent by Kamal's two brothers living

in the Middle East. Around the year 2000, they thought the

dream to have a house of their own would soon be a reality.

But it took Kamal, the sibling in charge of building the dream

house, two long years to get the plan through Rajuk. The plan

first got caught in the official procedural web and was later

faced with regulatory barrier as by then a new rule was introduced

that required a 12 foot wide entry path for any house. The

house that Kamal was set to build the entry road measured

only 8.33 feet in width, and it was in accordance with the

rule during submission.

If Rajuk

is strict in passing a plan of people's dream houses, which

cost Kamal Ahmed not only two precious years but also a certain

undisclosed amount of money, how come the city's residential

areas are turning into concrete jungles unsuitable for living?

Adabor

was a flood zone that fell in the hands of the private developers.

According to one of the town planners of Rajuk, the government

recognises the plans but they are chalked out by the private

developers. And the Rajuk planners approve them in accordance

with 'Town Improvement Act' of the 50s.

The

first Master Plan for Dhaka was put on paper in 1957, when

the population was 1,025,000, of which 100,000 lived in Naraynganj.

The only congested area was what the planners referred to

as 'Old central area' meaning Old Dhaka. After 39 years, in

1992 another plan that set the strategies for the years 1995

to 2015 came into being. Grappling with two sets of policy

issues, one of 'rapid urbanisation' and the other of 'effective

management of large metropolitan centres', it provided a map

for development of urban areas. "A huge amount has been

spent to create this plan which is a difficult read, you cannot

get a clearly defined set of rules from the text," opines

Saif-ul-Haque, an architect who believes that when planning

for a city one should also take into account the context of

the whole country, as did the planners of the city of Berlin.

"If the Bank authorities could hire experitise of the

MIT consulting team to plan their city, why did we have to

go for a private company that we never even heard of having

any experience in planning cities?" argues Haque. The

first Master Plan for Dhaka was put on paper in 1957, when

the population was 1,025,000, of which 100,000 lived in Naraynganj.

The only congested area was what the planners referred to

as 'Old central area' meaning Old Dhaka. After 39 years, in

1992 another plan that set the strategies for the years 1995

to 2015 came into being. Grappling with two sets of policy

issues, one of 'rapid urbanisation' and the other of 'effective

management of large metropolitan centres', it provided a map

for development of urban areas. "A huge amount has been

spent to create this plan which is a difficult read, you cannot

get a clearly defined set of rules from the text," opines

Saif-ul-Haque, an architect who believes that when planning

for a city one should also take into account the context of

the whole country, as did the planners of the city of Berlin.

"If the Bank authorities could hire experitise of the

MIT consulting team to plan their city, why did we have to

go for a private company that we never even heard of having

any experience in planning cities?" argues Haque.

The

Dhaka Metropolitan Development plan (1995-2015), approved

on 3-8-1997 and published in the Bangladesh Gazette on August

4, 1997, was the work of an American company -- Mott Mac Donald

Ltd. They were awarded the subcontract in 1992, and the plan

saw its completion in 1996. Although the plan includes a Master

Plan and even Detailed Area Plans and Structure Plan, the

issue of 'density control' remains a blurry area. The bulk

of construction, according to the plan, has to be consistent

with the demand that the area will place on its infrastructure

including roads and utility supplies. Even if this phrase

were taken into account the residential areas of Dhaka would

look different today. The

Dhaka Metropolitan Development plan (1995-2015), approved

on 3-8-1997 and published in the Bangladesh Gazette on August

4, 1997, was the work of an American company -- Mott Mac Donald

Ltd. They were awarded the subcontract in 1992, and the plan

saw its completion in 1996. Although the plan includes a Master

Plan and even Detailed Area Plans and Structure Plan, the

issue of 'density control' remains a blurry area. The bulk

of construction, according to the plan, has to be consistent

with the demand that the area will place on its infrastructure

including roads and utility supplies. Even if this phrase

were taken into account the residential areas of Dhaka would

look different today.

"The

plan is an incomplete one and a poorly detailed-out project,

many things are open to different interpretations," says

Haque. "If you plan for one crore people, you have to

decide where they will reside. Residences of the rich, the

middle class and the other classes have to be located. The

areas they will go to work and how they will even travel to

their respective work places, these things are addressed in

a master plan for any city," adds Haque. He believes

that one cannot expect a residential area to remain untouched

by other developments and can include conveniences such as

schools and market places provided that they do not encroach

upon the residential ambience of the localities. "The

plan is an incomplete one and a poorly detailed-out project,

many things are open to different interpretations," says

Haque. "If you plan for one crore people, you have to

decide where they will reside. Residences of the rich, the

middle class and the other classes have to be located. The

areas they will go to work and how they will even travel to

their respective work places, these things are addressed in

a master plan for any city," adds Haque. He believes

that one cannot expect a residential area to remain untouched

by other developments and can include conveniences such as

schools and market places provided that they do not encroach

upon the residential ambience of the localities.

He

looks back to the early days of Dhanmondi, when it was acquired

by the Pakistan government, he remembers, "The entire

area was a stretch of land for cultivation-- dhan

(Paddy) and mondi, the two words stand proof of that."

And Haque is emphatic about one thing, which has to do with

purity of a residential area. He

looks back to the early days of Dhanmondi, when it was acquired

by the Pakistan government, he remembers, "The entire

area was a stretch of land for cultivation-- dhan

(Paddy) and mondi, the two words stand proof of that."

And Haque is emphatic about one thing, which has to do with

purity of a residential area.

Dhanmondi

now has too many schools, colleges and even universities,

all of them are private, and they cater to the recruits that

come from a much wider radius. And one of the unusual features

of this vast development area is that there were no allocated

zones for community centres and market areas in the real plan.

At present they are sprouting like mushrooms. As for the residential

buildings, since Rajuk had withdrawn the restriction on vertical

growth, (which was regulated to three stories before the time

when six stories were declared as the limit) residential areas

like Dhanmondi and Gulshan saw a rapid growth in large apartment

buildings courtesy of the private developers. "It was

in the late '80s, during the Ershad regime that the limit

was set to six stories," explains Haque.

Gulshan Lake

At

last the fate of Gulshan Lake seems a bit on the brighter

side. As Gulshan Society, comprising of representatives of

Gulshan residents, recently met the Rajuk Chairman M Shahid

Alam, he promised to take all-out measures to save the lake

from deteriorating any further. Rajuk Chief Engineer Emdadul

Islam said a project is being planned to remove all the link

roads across the lake and construct six bridges in their place.

Although there was a Supreme Court ruling that urged Rajuk

to take immediate steps to protect the lake both from encroachment

and waste dumping the implementation of the plans that Rajuk

chalked out in 2000, did not receive the nod of the Planning

Commission. The Rajuk concept paper includes reconstruction

of bridges and culverts, drainage systems and relocation of

electric poles, which is estimated to cost TK 33.68 crore,

an amount, a recent newspaper report claims, will go to save

the lake. The 200 acres of total lake area became a centre

of attention when private encroachers threatened to fill out

the lake bed. It is alleged by many that even Rajuk has developed

several plots by filling parts of the lake that occupies a

vast region. In the meeting with the Rajuk Chairman, civil

bodies stressed the need to stick to the Dhaka Master Plan

that clearly defines water bodies in and around the city as

essential to its eco-system. It is a pity that even after

promulgation of the Wetland Protection Act in 2000, the lake

still runs the risk of being reduced. However, recently, Rajuk

has taken steps to remove all the poles marking the areas

encroachers were intent on grabbing. It is a positive sign

to save the planned residential enclave. At

last the fate of Gulshan Lake seems a bit on the brighter

side. As Gulshan Society, comprising of representatives of

Gulshan residents, recently met the Rajuk Chairman M Shahid

Alam, he promised to take all-out measures to save the lake

from deteriorating any further. Rajuk Chief Engineer Emdadul

Islam said a project is being planned to remove all the link

roads across the lake and construct six bridges in their place.

Although there was a Supreme Court ruling that urged Rajuk

to take immediate steps to protect the lake both from encroachment

and waste dumping the implementation of the plans that Rajuk

chalked out in 2000, did not receive the nod of the Planning

Commission. The Rajuk concept paper includes reconstruction

of bridges and culverts, drainage systems and relocation of

electric poles, which is estimated to cost TK 33.68 crore,

an amount, a recent newspaper report claims, will go to save

the lake. The 200 acres of total lake area became a centre

of attention when private encroachers threatened to fill out

the lake bed. It is alleged by many that even Rajuk has developed

several plots by filling parts of the lake that occupies a

vast region. In the meeting with the Rajuk Chairman, civil

bodies stressed the need to stick to the Dhaka Master Plan

that clearly defines water bodies in and around the city as

essential to its eco-system. It is a pity that even after

promulgation of the Wetland Protection Act in 2000, the lake

still runs the risk of being reduced. However, recently, Rajuk

has taken steps to remove all the poles marking the areas

encroachers were intent on grabbing. It is a positive sign

to save the planned residential enclave.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2004

|