Art

Everyday Everyday

Aesthetics

Mustafa

Zaman

It

was in 1990, when SM Sultan visited the home of the artist

Priyobhashini and ecstatically declared, "You are a true

artist" that Priyabhashini woke up to her own talent.

Before that deciding moment she never thought much of her

own sculptural creations, she didn't even considere them to

be art works. She made them as she felt a compulsion to do

so. However, she took immense pleasure as a root of tree,

a trunk or a part of it gradually took a different shape in

her hands.

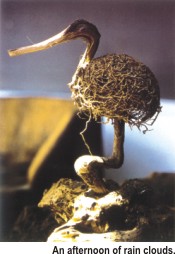

Driftwood,

roots and trunks constitute her vehicle. She courses these

articles -- her base metal -- through process of transmutation.

As they change and start to take recognisable shapes of humans

or birds, she stops at a point with the mutation remaining

incomplete. Her art banks on the vaguenesses that the incompleteness

of the transformation that she, as an artist, initiates.

However,

as sculptures they are complete. The vision, with which she

is able to determine the fate of the raw material she deals

with, brings into view the essence of a human or two, or a

bird in its contemplative solitude.

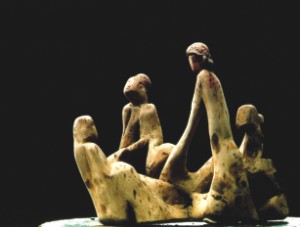

With

birds she remains a calm observer, rarely showing one in flight

or in any other posture but stillness, with humans she sheds

her reservation, and presents them in gaits of ecstatic turmoil,

not of psychological nature, but of a physical one. Priyobashini's

intertwined roots of trees turned into human couples are sights

of joy. She is unreserved in her depiction of the vortex of

sensation her couples find themselves into. The material she

works with plays a role. While working with a root that looks

like a cluster of muscles in motion, her desired end is always

swirling and gesticulating humans. With

birds she remains a calm observer, rarely showing one in flight

or in any other posture but stillness, with humans she sheds

her reservation, and presents them in gaits of ecstatic turmoil,

not of psychological nature, but of a physical one. Priyobashini's

intertwined roots of trees turned into human couples are sights

of joy. She is unreserved in her depiction of the vortex of

sensation her couples find themselves into. The material she

works with plays a role. While working with a root that looks

like a cluster of muscles in motion, her desired end is always

swirling and gesticulating humans.

She

has been doing it for more than fifteen years. The visual

ecstasy that she harps on has struck a different chord in

many a mind. However, the recent solo show at Bengal Gallery

of Fine Arts, showcases her already familiar art form and

more. She displays her own brand of horticulture.

"I

used to throw away a good portion of the tree trunks after

I have finished my sculptures.

And

suddenly one day I thought, why not use them as handmade pots

for my plants," she confides. This process of turning

tree trunks or even roots into a plant-pot has started a whole

new cycle in her life. The results are displayed in the gallery,

but these experiments in plantation took years to master. And

suddenly one day I thought, why not use them as handmade pots

for my plants," she confides. This process of turning

tree trunks or even roots into a plant-pot has started a whole

new cycle in her life. The results are displayed in the gallery,

but these experiments in plantation took years to master.

"The

Pakur tree that you see in the gallery, has been with me for

last fourteen years," says the artist. She makes it a

point to treat these trees as part of her family. She is always

on the look out for a roadside sapling or a small tree that

soon will be uprooted by anyone next to us.

Both

with the material for her sculpture and plant, Priyobhashini

remains an artist dependent on indigenous resources. Hers

certainly is an independent and alternative way. "Even

if I go somewhere to attend a seminar and I stumble into a

sapling or a tree trunk, I pick it up and take it home,"

she reveals how she accumulates her raw material. At one time

she couldn't help nullify her husband's request to keep her

hands off a tree that she desired to save.

It

was during a funeral and she was as usual adamant to get her

tree to replant it in one her pots. To make things look civilised,

she went back in the evening to pick up her tree.

Though

a certain sense of beauty governs Priyabhashini's world, she

makes it a point that things don't get bogged down in the

desire to decorate the house. Although her plants are meant

for urbanites who lack proper space for planting trees, she

says, "It is more about bringing a patch of green in

your own home than about decorating the home. It is mostly

about saving the trees."

In

her effort to keep this process going, she has made many an

attempt to rescue roadside saplings. She, in this respect,

is true to her word. Her total presentation comprises only

of the indigenous variety that we often ignore, as they do

not easily appeal to the urban sets of eyes.

Apart

from the huge sculptural pieces or plants, there are simple

craft-like presentations. The best example of this is the

Pakur tree and the way it was adorned with encircling boats.

The tree itself is of human-height and she turns it into an

occasion to create a virtual miniature ghat -- a river station

where boats are anchored under such trees. To make her small

boats, Priyabhashini uses the outer coverings of the pod from

which the coconuts emerge at the early stage of flowering.

Their beauty is in their simplicity. She is crafty, but never

too much to make her works look like products. Apart

from the huge sculptural pieces or plants, there are simple

craft-like presentations. The best example of this is the

Pakur tree and the way it was adorned with encircling boats.

The tree itself is of human-height and she turns it into an

occasion to create a virtual miniature ghat -- a river station

where boats are anchored under such trees. To make her small

boats, Priyabhashini uses the outer coverings of the pod from

which the coconuts emerge at the early stage of flowering.

Their beauty is in their simplicity. She is crafty, but never

too much to make her works look like products.

What

is it that makes her work so fraught with emotion? It is the

seemingly pristine look and the feel of the natural. The manipulation

is so subtle that her work gives the impression as if they

each were formed through a long natural process. The patina

of the old and weathered wood also adds to the aura that she

strives to create. Usually she sticks to colours that hide

any sign of sanding. And polishing is avoided altogether.

Yet in this show a couple of new works veer to a different

look -- they are sand to show the true colour of the wood,

which is yellow-white. The work titled "Emon diney tarey

bola jaey" (In such a day you could tell one) is one

human-like form growing out of another. They are a couple

-- mutating towards an unknown end.

The

same sense of metamorphosis is brought into the work "Shey

rater kotha" (The story of that night). The suggestion

of humans are even fainter in this tangle of roots embracing

one another. The effect of having to confront piece like this

lying on floor, presented without a stand or plinth, is a

surreal one. It seems like a naive or expressionist version

of the celebrated Laocoon sculpture of the Hellenic Greece.

Only the grandeur is dropped to initiate the communication

on a human level.

With

all the twists and turns, with all the crafty handling of

material, Priyabhashini's works retain a simplicity akin to

the age-old tradition of crafts in Bangladesh. Perhaps it

is this traditional pull that manifests in her work and makes

them look humble and communicable.

In

the present show, there is an effort to handle an epic theme

in her large-scale work titled -- "Sea-bound". The

sculpture is a feast for the eyes, but it also stands like

a puzzle to be solved by the onlookers. Here, her ambition

exceeds the human level, and it is at the human level that

she comfortably hovers and delivers her emotive (but mute

in their emotional expression) sculptures.

Priyabhashini

displayed a lot of mixed breed plants and creepers. They all

go back to the time when she started working with plants,

which was in 1994. However, in this show the most interesting

species is the fungi that she mounted on the wall. In a number

of painting-like presentations, she composes the tree burke

with soft, white fungi in them. Nigther her tree, nor these

works are presented to create the unreal and sophisticated

look of a Japanese bansi. They thrive in their natural energy

and give the urbanites a chunk of the almost untouched nature

itself. Priyabhashini

displayed a lot of mixed breed plants and creepers. They all

go back to the time when she started working with plants,

which was in 1994. However, in this show the most interesting

species is the fungi that she mounted on the wall. In a number

of painting-like presentations, she composes the tree burke

with soft, white fungi in them. Nigther her tree, nor these

works are presented to create the unreal and sophisticated

look of a Japanese bansi. They thrive in their natural energy

and give the urbanites a chunk of the almost untouched nature

itself.

Though

her target audience is the people who have long ceased to

live in a natural environment, her vision favours the natural

and the rustic in most occasions. Made for people living in

flats, her works strikes a balance between the urban taste

and the rural inheritance. She even dares to negate what the

architectural setting allows for. She says, "I have plans

for designing interiors, where everything geometrical will

be overwhelmed by what is natural. I have plans to plant big

trees on big logs as the pot."

We

only hope that she makes it a reality.

The

exhibition kicked off on July 10 and will last till July 26.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2004

|