|

Impressions

Out

with the

New and in

with the Old

Lally

Snow

‘Dhaka

is a place of last resort for the dispossessed and displaced

from the countryside.' So reads my, by now dog eared and much

thumbed through yet trusty guidebook. A modern twist on the

story of Dick Wittington and perhaps not the most positive

of introductions to the capital of a developing country and

a far cry from the usual accolades attributed to other, perhaps

more sophisticated cities around the world. ‘Dhaka

is a place of last resort for the dispossessed and displaced

from the countryside.' So reads my, by now dog eared and much

thumbed through yet trusty guidebook. A modern twist on the

story of Dick Wittington and perhaps not the most positive

of introductions to the capital of a developing country and

a far cry from the usual accolades attributed to other, perhaps

more sophisticated cities around the world.

As

a relative newcomer to the city, and Dhaka being my first

port of call, I was, and still am intrigued by it. Cities,

by their very nature, are big. They seep like a drop of ink

on blotting paper silently spreading into that place where

the land meets the sky; oblivion. Dhaka is no exception. The

other day the lofty heights of a friends eleventh floor apartment

gave me fantastic views of the city from all angles, but its

edge could not been seen and, fantastical though it may sound,

I could almost imagine it sprawling across the whole globe,

in synchrony with the low lying clouds, an endless sea of

telegraph poles, wires, high rise buildings, domes of mosques

and, of course, rickshaws. (Would Dhaka be complete without

its rickshaws?)

I

have the misfortune of being female and European looking (and

perhaps a little naive), but down on the ground Dhaka proves

to offer a new experience every day and, if I am honest, these

experiences are sometimes not particularly enjoyable. What

first strikes the outsider is the sheer volume of noise. When

I first learnt to drive, my instructor reprimanded me on countless

occasions for playful yet illicit use of the cars' horn. '

As you can see from page 47 paragraph c of your manual,' he

would say gravely making notes with an ominous red pen, 'the

horn is only to be used as a warning to other cars who might

not see you around a narrow corner, never in anger, haste

or jest. Emergencies only.' But here, in Dhaka, anything goes.

Hoot for attention; ring in annoyance; hoot 'get out of my

way,' when words become redundant; ring to mean left or right

or straight on or all three; hoot to mean hurry up; ring to

mean slow down; hoot for fun, even. There are no rules and

if there were, rules are meant to be broken, or so the saying

goes. I

have the misfortune of being female and European looking (and

perhaps a little naive), but down on the ground Dhaka proves

to offer a new experience every day and, if I am honest, these

experiences are sometimes not particularly enjoyable. What

first strikes the outsider is the sheer volume of noise. When

I first learnt to drive, my instructor reprimanded me on countless

occasions for playful yet illicit use of the cars' horn. '

As you can see from page 47 paragraph c of your manual,' he

would say gravely making notes with an ominous red pen, 'the

horn is only to be used as a warning to other cars who might

not see you around a narrow corner, never in anger, haste

or jest. Emergencies only.' But here, in Dhaka, anything goes.

Hoot for attention; ring in annoyance; hoot 'get out of my

way,' when words become redundant; ring to mean left or right

or straight on or all three; hoot to mean hurry up; ring to

mean slow down; hoot for fun, even. There are no rules and

if there were, rules are meant to be broken, or so the saying

goes.

The

volume of traffic and pollution coincides with this noise

and likewise there does not seem to be much consistency in

driving standards. Although there are lines to indicate lanes,

a loud toot seems to take precedence over actually adhering

to these lanes and a wave of the arm in any which direction

suffices to communicate to any one interested in a desired

path. However, I am accustomed to this way of travel now.

Pollution levels, as we all know, are higher here than almost

anywhere else in the world. This combined with the general

sense of decay that seems to emanate from building projects

left unfinished in certain corners of the city, makes Dhaka

appear, to me at least, a little lost, not least pandemonic.

But

perhaps this is all a little superficial. What really amazes,

shocks, disturbs and upsets me about Dhaka is the poverty.

Do not get me wrong, I have not just emerged from a world

where everything is safe and sure and where everyone is comfortable.

I know that poverty is rife and have seen countless limb-less

and emaciated examples of it from Laos to London. Until now,

Cambodia had the most profound sense of poverty and degradation

with its child prostitutes, numerous amputees, a prevailing

sense of loss. But

perhaps this is all a little superficial. What really amazes,

shocks, disturbs and upsets me about Dhaka is the poverty.

Do not get me wrong, I have not just emerged from a world

where everything is safe and sure and where everyone is comfortable.

I know that poverty is rife and have seen countless limb-less

and emaciated examples of it from Laos to London. Until now,

Cambodia had the most profound sense of poverty and degradation

with its child prostitutes, numerous amputees, a prevailing

sense of loss.

But

it is nothing compared to Dhaka. I saw one woman in Phnom

Penh, pick her way through the rubbish directly outside the

tourist vicinity, trying to salvage some sort of existence

from the waste of others. Just one and I was horrified. I

see that here daily and the presence of barefooted, half-naked

beggars is like no where else I have been but I am aware that

to the permanent resident this is the norm. The strangest

thing, though, for me, is the disparity of wealth. In perfect

antithesis, it is not unusual to see a surprisingly new looking

4x4 next waiting in traffic next to one of these barefooted

down and outs. Or a smart residential complex just in front

of one of the city's many shantytowns.

On

my journey into work, I have to pass a number of busy flyovers

and areas of rancid wasteland. 'So what?' you say, 'This is

Dhaka. Get over it.' But I cannot. Poverty is one thing, but

it is the overriding sense of hopelessness that prevails.

Static human lives seem to cling to the edge of the road,

some lying, some standing both un-seeing and un-doing in the

filth and squalor.

When

I first arrived in this illustrious city a friend told me

that I must go to Old Dhaka especially 'The Pink Palace,'

and it sounded intriguing. I duly read up in my faithful guide

book and set off, clearly stating to the CNG driver 'Ashan

Manzil'. Half an hour later we were outside the National Museum,

and after much gesticulation and exchange of buzzwords such

as 'Old Dhaka please,' 'Eeer, Shankharia Bazar?' 'Ummm, Burigana

River?' and 'na National Museum!' I found myself at the edge

of Old Dhaka although where exactly, I do not know.

Instantly

noticeable was the absence of road noise. If my ears had been

ringing from the sounds of congestion, they were now ringing,

literally, from the symphony of rickshaw bells. Immediately,

I was enchanted as before me lay a maze of winding streets

and dilapidated yet romantic looking buildings not a neon

sign or high rise building in sight. I walked for a while

taking in the new array of sights and smells. Due to the relative

lack of traffic the air was filled with delicious, and to

me exotic, aromas both sweet and savoury, I passed a girl

weaving together flowers and smelt their nectar, rice sellers

measured and weighed their bounty and I heard individual grains

hit the ground amid laughs and chatter. Although I was still

an object of curiosity, people were far too busy with what

they were doing to bother with me and at last I was anonymous.

It was refreshing and I felt refreshed. Instantly

noticeable was the absence of road noise. If my ears had been

ringing from the sounds of congestion, they were now ringing,

literally, from the symphony of rickshaw bells. Immediately,

I was enchanted as before me lay a maze of winding streets

and dilapidated yet romantic looking buildings not a neon

sign or high rise building in sight. I walked for a while

taking in the new array of sights and smells. Due to the relative

lack of traffic the air was filled with delicious, and to

me exotic, aromas both sweet and savoury, I passed a girl

weaving together flowers and smelt their nectar, rice sellers

measured and weighed their bounty and I heard individual grains

hit the ground amid laughs and chatter. Although I was still

an object of curiosity, people were far too busy with what

they were doing to bother with me and at last I was anonymous.

It was refreshing and I felt refreshed.

Of

course, in New Dhaka there are signs of hope and development.

Buildings are built albeit slowly, markets prosper with the

throng of customers, and the very presence of all this traffic

is a sign of commerce to me at least. In last weeks heavy

rain I was amused, if a little bewildered, to see people carrying

on regardless of the torrent of water descending from the

heavens. Likewise in the blistering heat, umbrellas become

sunbrellas. Whatever the weather, life goes on. In contrast

when it snows in England the whole country goes into a neurotic

frenzy with roads becoming blocked and power failures; if

there are leaves on the lines (yes leaves), trains don't run;

when it is hot, the hospitals become filled with individuals

suffering from sunstroke, mild burns and dehydration; when

it rains people go without lunch for fear of getting wet.

Life does not go on.

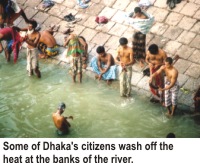

People

have since told me that Old Dhaka is one of the most over

populated and poor places of the city and that it is usual

for buildings to collapse at random due to the lack of original

planning. In retrospect, perhaps this is evident, but at the

time, it was not. Yes, there were rubbish pickers, yes there

were signs of unchecked poverty but even above the shop fronts

life looked busy, cheerful and, well it looked hopeful. In

front of Ashan Manzil, which incidentally was closed, could

be seen the hustle and bustle of the river. Later on, from

the vantage point of the Gulistan crossing ant-like people

smiled and splashed as they washed, traded with each other

in earnest, or merely sat pensively on their boats.

From

the Gulistan crossing that afternoon, there was a break in

the clouds and I could see the tale of the two cities, and

suddenly the ending appeared more promising and optimistic.

May be, one day, Dhaka will be returned to its former glory

as a city so lusted after by Mughals and Empire builders alike.

If the younger generations can learn from their predecessors,

so too can the New learn from the Old.

Lally

Snow is a UK-based journalist interning with The Daily Star

Copyright (R)

thedailystar.net 2004

|