|

Cover

Story

Cheated

Out of

their Own Land

Morshed

Ali Khan

Photographs by Philip Gain

The

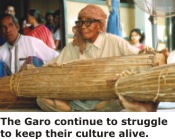

Garos of Pirgacha are a vibrant community, celebrating their

traditional festivals and struggling to keep their culture

alive. However, in spite of their impressive record of educating

themselves and giving women the economic freedom absent in

most communities, they are an indigenous people under immense

threat. Over the decades, this peaceful community has been

cheated out of their most precious possession--their land. The

Garos of Pirgacha are a vibrant community, celebrating their

traditional festivals and struggling to keep their culture

alive. However, in spite of their impressive record of educating

themselves and giving women the economic freedom absent in

most communities, they are an indigenous people under immense

threat. Over the decades, this peaceful community has been

cheated out of their most precious possession--their land.

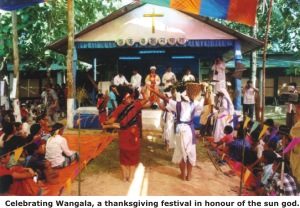

From the

very early morning of October 31, hundreds of Garo or Mandi

men, women and children, in an amazing display of colourful

traditional outfits, started converging at the Pirgacha High

School, in Madhupur under Tangail district, about 150 kilometres

from Dhaka. As they entered the festooned playground, young

Garo girls standing at the entrances blessed each individual,

imprinting the forehead with white rice colour. Many brought

with them offerings to the church from their harvest of vegetables

and grains and lined them up in small buckets before the dais.

The visitors listened carefully to the prayers sitting under

a large overhead covering. The leaders of the Saint Paul's

Church conducted the prayers while young Garo men and women

sang devotional songs in the background.

As

the October sun rolled towards the afternoon, the prayers

were over and the party began with traditional dances, songs

and short plays. In the evening, villages woke up to celebrate.

Every family cooked traditional dishes and every Garo wore

their best dress. Men and women sipped chu, a home

made rice beer, until some started singing and dancing in

the neat courtyards of the village homes. As

the October sun rolled towards the afternoon, the prayers

were over and the party began with traditional dances, songs

and short plays. In the evening, villages woke up to celebrate.

Every family cooked traditional dishes and every Garo wore

their best dress. Men and women sipped chu, a home

made rice beer, until some started singing and dancing in

the neat courtyards of the village homes.

For

the 10,325 members of the Catholic Garo community living under

the Pirgacha mission, it was the day of wangala or

thanksgiving. In Garo culture wangala is celebrated

every year in honour of the sun god, Saljong, after rice is

harvested in the hills. There are other reasons for such an

overwhelming participation in wangala in the 32 villages

of Pirgacha.

While

the literacy rate of the entire population of Bangladesh is

recorded as 32 percent, in Pirgacha more than 98 percent of

the Garo population are listed as literate, many of them with

higher education. The mission runs 24 primary schools educating

1,700 children with 50 qualified teachers, most of whom are

female. The high school in Pirgacha has 12 teachers and 550

students, who are automatically introduced to computer education

in class 9.

Thanks

to the development activities of the church and a host of

famous national and international NGOs, including World Vision,

CARE, CARITAS, Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC)

and the United States Peace Corps, every Garo household in

the 32 villages represents a model way of living. Every household

in the villages has an efficient sanitary system that has

over the years almost totally wiped out attacks of diseases

caused by worms. Every family has a tubewell system that ensures

pure drinking water. Hygiene in the traditional tin-roofed,

earthen houses is rigorously maintained. The small open space

in front of each house is adorned with flower plants. Animal

breeding is very common with villagers rearing poultry, pigs,

goats and even turtles. The transportation system too, is

efficient enough to allow bananas and pineapples, the two

principal produces of the area, to be carried to the market

place. Thanks

to the development activities of the church and a host of

famous national and international NGOs, including World Vision,

CARE, CARITAS, Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC)

and the United States Peace Corps, every Garo household in

the 32 villages represents a model way of living. Every household

in the villages has an efficient sanitary system that has

over the years almost totally wiped out attacks of diseases

caused by worms. Every family has a tubewell system that ensures

pure drinking water. Hygiene in the traditional tin-roofed,

earthen houses is rigorously maintained. The small open space

in front of each house is adorned with flower plants. Animal

breeding is very common with villagers rearing poultry, pigs,

goats and even turtles. The transportation system too, is

efficient enough to allow bananas and pineapples, the two

principal produces of the area, to be carried to the market

place.

One

of the most remarkable things in the Garo community is the

level of empowerment of women. The Garo tribe gives all rights

of property to the women. It is the groom who moves into the

bride's house and lives with her and only with the permission

of the wife can he act as a mere administrator of the real

estate. All real property and possessions automatically belong

to the woman. Garo law does not allow men to own property

and so they cannot sell anything without the permission of

the wife's side of the family. According to US-born Reverend

Eugene E Homerich of the Pirgacha church, who has been officially

adopted in the Mandi tribe for his 50 years of services, "

This is an avuncular society where the mother's brother has

more power over the child than the father. The British, Pakistani

and now the Bangladeshi governments have recognised the customary

law." One

of the most remarkable things in the Garo community is the

level of empowerment of women. The Garo tribe gives all rights

of property to the women. It is the groom who moves into the

bride's house and lives with her and only with the permission

of the wife can he act as a mere administrator of the real

estate. All real property and possessions automatically belong

to the woman. Garo law does not allow men to own property

and so they cannot sell anything without the permission of

the wife's side of the family. According to US-born Reverend

Eugene E Homerich of the Pirgacha church, who has been officially

adopted in the Mandi tribe for his 50 years of services, "

This is an avuncular society where the mother's brother has

more power over the child than the father. The British, Pakistani

and now the Bangladeshi governments have recognised the customary

law."

But

this is just one side of the story. The Mandis have their

problems too. Although for centuries the tribe, originating

from Southwest China and Tibet, has lived in the 'Sal' forest

with their own religion, culture and way of life, their right

to land till date remains uncertain. The first onslaught on

the Garo tribe probably came when the British Colonial Government

of India granted the entire Madhupur Tract to the Raja of

Natore in 1927. The Raja dedicated the forest to the god Govinda

under the title "Debittor" or "a gift to the

gods". The Garos were allowed to live on homestead plots

paying a yearly tax. Garo women tenants were also granted

permission to register low-lying land in their names. The

registration started from 1892 and incorporated again in the

Cadastral Survey of 1914-1918. By an exception of the law,

certain Aboriginal Tribes enumerated in the Bengal Tenancy

Act were exempt from the Succession Act of 1865. This exemption

recognises the Garo Law of Succession and Inheritance. Again,

by an Act of Law in 1972, Bangladesh recognised all previous

laws. This established the registration of land under the

Bengal Tenancy Act. But

this is just one side of the story. The Mandis have their

problems too. Although for centuries the tribe, originating

from Southwest China and Tibet, has lived in the 'Sal' forest

with their own religion, culture and way of life, their right

to land till date remains uncertain. The first onslaught on

the Garo tribe probably came when the British Colonial Government

of India granted the entire Madhupur Tract to the Raja of

Natore in 1927. The Raja dedicated the forest to the god Govinda

under the title "Debittor" or "a gift to the

gods". The Garos were allowed to live on homestead plots

paying a yearly tax. Garo women tenants were also granted

permission to register low-lying land in their names. The

registration started from 1892 and incorporated again in the

Cadastral Survey of 1914-1918. By an exception of the law,

certain Aboriginal Tribes enumerated in the Bengal Tenancy

Act were exempt from the Succession Act of 1865. This exemption

recognises the Garo Law of Succession and Inheritance. Again,

by an Act of Law in 1972, Bangladesh recognised all previous

laws. This established the registration of land under the

Bengal Tenancy Act.

The

bad news for the unsuspecting Garos came in 1984 when the

government in a gazette notification placed much of the Modhupur

tract under the category of the Government Forest Land. The

whole procedure was completed without any notification to

the tenants (Garos). When the government move was challenged

in the court of justice and in the land settlement office,

the authorities allegedly refused to give any opportunity

to the Garos to produce their documents. The government then

refused to recognise the tenancy rights and barred Garos from

paying any land tax, terming their land documents as "bogus". The

bad news for the unsuspecting Garos came in 1984 when the

government in a gazette notification placed much of the Modhupur

tract under the category of the Government Forest Land. The

whole procedure was completed without any notification to

the tenants (Garos). When the government move was challenged

in the court of justice and in the land settlement office,

the authorities allegedly refused to give any opportunity

to the Garos to produce their documents. The government then

refused to recognise the tenancy rights and barred Garos from

paying any land tax, terming their land documents as "bogus".

The events

of 1984 sealed the fate of the famous Madhupur Tract and made

the Garos defenseless against reckless government decisions

of indiscriminate Asian Development Bank-funded tree plantation

projects. Successive governments have served eviction notices

to the Garos, while depleting the local Sal forests and sometimes

replacing them with totally unknown species of imported trees,

highly detrimental to environment and local inhabitants. Interestingly,

once the Bangladesh Tea Board proposed to remove the entire

Garo population to the tea gardens elsewhere under a scheme

of 'creating job opportunities' for the tribal population

to work as coolies. The government failed to sell the scheme.

Then

in October 1996, the government had a new idea about Madhupur

Tract, and this time it was the World Bank providing the funds.

The scheme envisaged creating 13 national parks and deporting

the 16,000 Garos into cluster villages. A high official of

the World Bank, Emilio Rozario flew in from the Philippines

to launch the project through the Forest Department under

the Ministry of Environment and Forest. An outcry from the

public representatives and the public put a stop to the planning. Then

in October 1996, the government had a new idea about Madhupur

Tract, and this time it was the World Bank providing the funds.

The scheme envisaged creating 13 national parks and deporting

the 16,000 Garos into cluster villages. A high official of

the World Bank, Emilio Rozario flew in from the Philippines

to launch the project through the Forest Department under

the Ministry of Environment and Forest. An outcry from the

public representatives and the public put a stop to the planning.

Most

recently the Forest Department started enacting a wall around

3,000 acres of Madhupur forest insisting that they were trying

to create an eco-park for safeguard of tree species and wildlife.

The move to encircle the forest at a cost of Tk 9.7 crore

and with a 10-foot-high wall outraged both the tribal and

non-tribal residents of the area. On January 3, 2004, 22-year-old

Piren Snal was killed and over 25 others were injured when

forest guards opened fire on the demonstrators.

Ajoy

Amree, Convenor of the Committee for Indigenous People's Land

Rights and Environment Preservation, says that the whole government

scheme is not only destroying the Garo culture but also threatening

their livelihood. Ajoy

Amree, Convenor of the Committee for Indigenous People's Land

Rights and Environment Preservation, says that the whole government

scheme is not only destroying the Garo culture but also threatening

their livelihood.

"We

have appealed to the Prime Minister to create a permanent

settlement for us and to abandon the scheme for a national

park," Amree added that the committee was also demanding

the withdrawal of false cases lodged by the forest department

and its contractors.

Sources

say that more than 3,000 cases have been lodged with the Madhupur

police station under the Revised Forest Act in which hundreds

of Garo men and women have been implicated. Most of those

accused now live under constant fear of persecution. Sources

say that more than 3,000 cases have been lodged with the Madhupur

police station under the Revised Forest Act in which hundreds

of Garo men and women have been implicated. Most of those

accused now live under constant fear of persecution.

Nere Dalgot,

a former teacher is implicated in eight cases, which he described

as "totally false and fabricated". He says he has

just served 45 days in prison.

"There

are Garo people against whom the forest department and its

contractors have lodged more than 50 cases and I can tell

you all these are totally fabricated cases," says Dalgot.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2004

|