|

Tribute

Arafat

Dies, Palestinian Dream Remains Unfulfilled

Yasser

Arafat was born Muhammad Abdul Rahman Abdul Raouf Arafat al-Qudwa

al-Husseini on 24 August 1929 in the Egyptian capital, Cairo.

His father, a Palestinian merchant living in Egypt, died during

the first Arab-Israeli war 20 years later.

Arafat's

youth is surrounded by uncertainty. He claimed to have been

born in Jerusalem but his Egyptian accent always revealed

his Cairo upbringing.

The

young Arafat is thought to have adopted the name Yasser --

and its epithet "Abu Ammar" -- while studying at

university in Egypt, to honour an Arab victim of the British

mandate in Palestine. From the beginning, Arafat was a powerful

grassroots activist. Initially, he was drawn towards Egypt's

Muslim Brotherhood, but soon became wedded to the idea of

armed struggle to reverse what the Palestinians call the 1948

Catastrophe. The

young Arafat is thought to have adopted the name Yasser --

and its epithet "Abu Ammar" -- while studying at

university in Egypt, to honour an Arab victim of the British

mandate in Palestine. From the beginning, Arafat was a powerful

grassroots activist. Initially, he was drawn towards Egypt's

Muslim Brotherhood, but soon became wedded to the idea of

armed struggle to reverse what the Palestinians call the 1948

Catastrophe.

That was

when the state of Israel was established on more than 70%

of Palestine, excluding what is now Jordan, which had been

under British rule.

At some

point after 1948, Arafat secretly founded Fatah, the Movement

for the Liberation of Palestine, with a few like-minded Diaspora

Palestinians, to achieve that reversal. Arafat later spoke

proudly of these days, when he salvaged World War II rifles

from the Egyptian desert to arm his organisation. Arafat's

style was often theatrical. In 1953 he sent Egypt's first

post-revolution leader, General Muhammad Neguib, a three-word

petition: "Don't forget Palestine." The words were

said to have been written in Arafat's own blood.

Arafat's

CV said that in 1956 he was commissioned as a lieutenant in

the Egyptian army and he served during the Suez crisis and

the Arab-Israeli war which followed. The expertise, which

Arafat gained in explosives and demolition, prepared him for

his role as the head of Fatah's military wing, al-Asifa -

the Storm - which started operations in 1965.

Al-Asifa's

job was to launch guerrilla attacks against Israel, mainly

from Jordan, Lebanon and Gaza, which was then under Egyptian

control. After Israel's 1967 crushing defeat of the Arab armies

and its capture of the West Bank and Gaza, Fatah was the only

credible force left fighting Israel. Arafat's reputation was

enhanced in 1968 with his courageous defence of the Jordanian

town of Karameh against superior Israeli forces.

Karameh

-- which means "dignity" in Arabic -- caused a surge

of optimism among Palestinians and raised the banner of Palestinian

national liberation in contrast to the failure of the Arab

regimes to challenge Israel. In 1969, Arafat was voted chairman

of the executive committee of the Palestine Liberation Organisation

(PLO), which had been formed four years earlier by the Arab

League. Initially based in Jordan, PLO fighters were driven

out by King Hussein in September 1970 -- later dubbed Black

September. Arafat led them to the Lebanese capital, Beirut.

In

subsequent years, guerrillas from various Palestinian factions

hit the headlines with hijackings, bombings and assassinations,

most notably the kidnapping and killing of 11 Israeli athletes

at the 1972 Munich Olympics. In

subsequent years, guerrillas from various Palestinian factions

hit the headlines with hijackings, bombings and assassinations,

most notably the kidnapping and killing of 11 Israeli athletes

at the 1972 Munich Olympics.

Arafat

refused to discuss such attacks, though he has always denounced

terrorism as a tactic. Whether or not he was personally involved

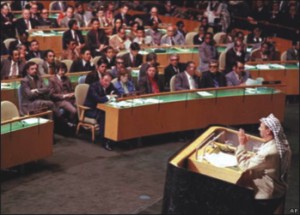

remains a matter of conjecture. In 1974 Arafat made a dramatic

entrance on the international diplomatic stage. Addressing

the United Nations General Assembly in New York, he told delegates

that he had come "bearing an olive branch and a freedom

fighter's gun -- do not let the olive branch fall from my

hand".

In the

1970s, the Palestinians were establishing a "state-within-a-state"

in Lebanon, which destabilised the country as they used it

as a launch pad for attacks on Israel.

In 1982,

Israeli Defence Minister Ariel Sharon launched his controversial

invasion of Lebanon to drive out the PLO. This resulted in

the expulsion of Arafat -- this time far from Israel's borders

to the North African State of Tunisia.

This was

the start of years of isolation that, in 1987, became more

acute with the outbreak of the Palestinian uprising, or intifada,

in the Israeli-occupied West Bank and Gaza. But one of Arafat's

great skills over the decades was his ability to harness the

Palestinian revolution, and he managed to identify the unarmed,

stone-throwing challenge to the occupation with his own leadership

-- though its origins had little to do with him.

Supposedly

wedded exclusively to the Palestinian cause, Arafat -- a Sunni

Muslim -- surprised the world in 1991 when he married Suha

Tawil, from a prominent Christian Palestinian family, with

whom he had a daughter, Zahwa. But the nuptials came at a

low point in Arafat's revolutionary career.

Having

ridden the intifada for four years, he had made a critical

mistake in 1990 by supporting Saddam Hussein during his invasion

and occupation of Kuwait. Support in the Gulf States dried

up, the Palestinian cause was never so marginalised and Arafat

had no choice but to make peace with Israel from a position

of weakness.

On

13 September 1993, Arafat and Israel's Prime Minister, Yitzhak

Rabin, appeared on the White House lawn after secret talks

facilitated by Norwegian diplomats. The two sides signed the

Declaration of Principles, an agreement allowing Palestinians

self-rule in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank town of Jericho

in return for the PLO's recognition of the Jewish state. On

13 September 1993, Arafat and Israel's Prime Minister, Yitzhak

Rabin, appeared on the White House lawn after secret talks

facilitated by Norwegian diplomats. The two sides signed the

Declaration of Principles, an agreement allowing Palestinians

self-rule in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank town of Jericho

in return for the PLO's recognition of the Jewish state.

But such

fundamental issues as Jewish settlements on occupied land,

the future of Palestinians who were made refugees in 1948

and the future of Jerusalem were left undecided. Though Arafat

returned in triumph to Gaza the following year, the peace

process was fraught with difficulties.

Rabin

was assassinated in November 1995 and, as President of the

Palestinian National Authority, Arafat struggled to define

his role and keep Israelis and Palestinians committed to what

he termed the "peace of the brave". By 2000, the

Oslo peace process had come to a dead end.

Arafat

was blamed by Israel and the US for the failure in July that

year of the peace talks at Camp David. He insisted though

that the deal he was offered was far less generous than it

has since been portrayed, and, as he put it, "the Arab

leader has not been born who would give up Jerusalem".

A new

intifada -- now armed, with Arafat at its heart -- was launched

in the West Bank and Gaza. Matters came to a head in December

2001 when, following a wave of suicide attacks, the Israeli

government -- led by Arafat's old adversary Ariel Sharon --

blockaded him in his West Bank headquarters, accusing him

of instigating the terror on Israel's streets.

Meanwhile,

the explosion of pent-up anger of Palestinians who had lost

faith in the peace process, and in Arafat's leadership, fed

the ongoing violence. Suicide bombings brought severe Israeli

retribution, which trapped and isolated Arafat in the ruins

of his bombed-out headquarters in Ramallah. Arafat died on

November 11 in a French hospital in Paris.

This

article was first published on bbcnews.com

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2004

|