| Cover Story

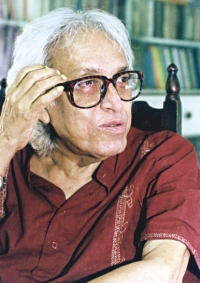

Shamsur Rahman

Verses from the Heart

His was a simple life but far from ordinary. It was spent being totally devoted to his love without any breaks or deviation. It was his uninterrupted passion to write poetry that has made sure that he will be remembered as an icon of Bangla literature, as an authentic painter of the Bangali soul. Shamsur Rahman will no doubt be missed for being a tangible assurance of Bangali identity. But he will remain immortal for his soul-lifting verses that have earned him the adoration and reverence of his compatriots. His was a simple life but far from ordinary. It was spent being totally devoted to his love without any breaks or deviation. It was his uninterrupted passion to write poetry that has made sure that he will be remembered as an icon of Bangla literature, as an authentic painter of the Bangali soul. Shamsur Rahman will no doubt be missed for being a tangible assurance of Bangali identity. But he will remain immortal for his soul-lifting verses that have earned him the adoration and reverence of his compatriots.

It was not just poetry-lovers who admired him but poets too who were inspired by his mode of writing. While his poetry thrived on urban dreams and disillusionment he was just as weak towards rural utopia and charged by the cultural spirit of post-independence. An abiding voice of the generation that shaped the political and cultural map of Bangladesh, Rahman has left behind a treasury of over 3000 poems that will continue to inspire his present admirers and those who will take their place in the future.

Although his ancestry lay in a village called Paratuli in Narshingdi district, Shamsur Rahman was a true Dhakaite, being born on October 23, 1929 in Mahuttuli in the old part of Dhaka. Rahman was born in a middleclass family and was the fourth among 13 brothers and sisters. He was a quiet child attending the Pogos School where he was an average student with little sign of the brilliance that would bloom in his later life.

Funnily enough, he wasn't even all that interested in literature but at age 18, after completing his Intermediate from Dhaka College, his mind was pretty much made up regarding his future. All he wanted to do was to write poetry as if it were the only thing that was worth pursuing.

His first poem was on the Bangla New Year and opened a floodgate for more poetry to come. "I was hardly aware whether what I was writing was poetry at all. I just felt like writing and went on", described the poet in an interview.

It was another gifted young man who also lived in the same neighbourhood as the poet, who goaded Rahman into getting his work published. This was the artist Hamidur Rahman who became the poet's closest friend and had his own share of glory as one of the main architects of the Shaheed Minar.

With his friend Hamidur constantly encouraging him, Rahman, with much trepidation went to the office of weekly 'Sonar Bangla' to meet its editor. His first poem was published on the first of January, 1949. While Rahman was ecstatic, his father was rather sceptical about his son's literary achievement. Writing poetry as a livelihood did not have much prospect especially to the stern father who was a mid-ranking police officer with little patience for what seemed like a frivolous vocation. "Can you become a poet like Humayan Kabir?" his father challenged him. The young poet impulsively answered: "If I become a poet I will become greater than Humayan Kabir!"He quickly left the scene before his father could retaliate.

With wife, Zohra Begum |

Later Rahman's father relented when his son received the Adamjee Award for poetry remarking "He is not as worthless as I had thought." This the poet recalled with much humour during an interview.

Encouraged by recognition as a poet, Rahman wrote with greater vigour. More and more of his poems got printed in 'Shonar Bangla' and 'Juger Dabi'. Meanwhile Rahman got admitted to the English department at Dhaka University and began to read voraciously. His favourites included Premendra Mitra and Budhadev Basu but it was Jibananda Das who became his life-long influence. He was not a serious student, hated classes and didn't think sitting for exams was really all that important. But he did love reading Shelley, Keats and Yeats.

Life could not be more full for the eager poet and consisted of writing poetry, reading and long sessions of adda at Aamtola and Madhur Canteen. Later this adda was transferred to Beauty Boarding in Old Dhaka and the Shaogat office. It was here that other poets gathered including literary stalwarts like Syed Shamsul Huq and Shahid Qadri.

After abandoning his student days, Rahman joined the daily 'Morning Sun' as a sub editor. He had a small stint at the state-owned radio station but went back to his first job because they agreed to pay him a larger amount. In 1968 he joined the then Dainik Pakistan (later renamed The Dainik Bangla) as assistant editor, later being promoted to editor. His journalistic career however, was only a livelihood and never a passion and he believed what one of his favourite poets Sudhindranath Dutta said about journalism - that it is harmful for writers.

On July 8, 1955 Rahman married Zohra Begum. He had seen her for the first time at a wedding and liked her, getting his family to send a proposal as per the tradition. The couple had two boys and three girls. Sumayra Rahman (1956), Fayiaz Rahman (1958), Fauzia Sabrin (1959), Wahidur Rahman Matin (1960-1979) and Sheba Rahman (1961).

Rahman has described the moment of inspiration to write a poem as a kind of flash that can come to you at the most unexpected moment. "Perhaps you will not believe it. But it really happens automatically. I cannot explain it...It happens that I am prepared with paper and pen but cannot write a single line. Sometimes when I am in bed all set to fall asleep when a line or two flashes through my mind. There is no respite then until I get up and start writing."

It is this spontaneity, this acting on an impulse that has produced some of the most

He left behind a sea of fans He left behind a sea of fans |

Syed Shamsul Huq, a long time friend writes in the condolence book Syed Shamsul Huq, a long time friend writes in the condolence book |

inspiring poetry from this prolific poet. During the liberation struggle when the Pak army unleashed its wrath on the people of Dhaka on the night of March 25, the city became suffocated by fear and grief. Like many others Rahman was forced to flee the city and rush to his village home for safety. It was while taking refuge in the serene rural setting that provoked one of Rahman's most celebrated poems - Shadhinota Tumi. "On reaching home we heaved a sigh of relief. One calm mid-day I was sitting by the pond. It was fenced by trees. On the other side of the pond a group of boys and girls were bathing and playing and shouting. A soft breeze wafting along from the south was giving me pleasant tickles. Suddenly two words flashed through my mind.'Shadhinota Tumi'."

The next lines flowed along effortlessly : Shadhinota tumi Rabi Thakurer ajor kabita.Abinashi gaan... Soon after this poem ended came another famous one: Tomake Powar jonne he shadhinota (It is to get you, this independence).

Nature, human emotions like grief, a sense of displacement or the urge to be free - these are common veins of his poetry.

In his autobiography, Rahman has mentioned a poem that has never been published. It was inspired by the encouragement of Amiyobhushan Chakraborty, a professor of English of the Dhaka University. The professor used to come to the university from Wari on his bicycle. Once Chakraborty took him to Phulbaria Railway Station and pointed out to a row of abandoned rail carriages and alluded to the plight of those living in the empty wagons who had nowhere else to go. They were refugees from Bihar. Chakraborty suggested that the two of them should write poetry about those displaced people. In the end it was Rahman's poem titled ' Koekti Din: Wagon e' (A few days, in a wagon) that found a place in a literary magazine published from Kolkata. The poem hauntingly describes the pathos of a refugee family who have taken shelter in an empty railway carriage, far away from their motherland. The poem describes the bleakness of refugee life, one that is torn with constant hunger, disease and deaths of loved ones and the gradual destruction of hope that is a consequence of displacement.

Rahman belongs to the lucky few who have been recognised for his life's work and has also been blessed by the love and adoration of thousands of fans. Certainly he was one of the most prolific poets with over eighty books to his credit.

Rahman as a young man delving into the world of poetry found himself deeply attracted to the poetry of Jibananda Das who became a constant source of inspiration. In the late 40s Rahman was a student of English at Dhaka University and had just started to contribute to the weekly Shonar Bangla, the only paper published from Dhaka. It was at that time that he came upon a book 'Dhushar Pandulipi' by Jibananda Das which his friend Zillur Rahman Siddiqui had lent him, though only for a day. Rahman spent the whole night pouring over Jibananda's dreamy imagery, drinking it all in so that the impressions would last him a lifetime. Rahman regarded Das with reverence and considered him the only exponent of modernism in the region that he is indebted to. It was Das's vivid recreations of idyllic nature combined with Rahman's own experience of living in old Dhaka that shaped the poet Rahman later became.

1. The poet out on the streets with artist Kamrul Hasan on March 23, 1971.

2. Receiving the prestigious D. Lit from Rabindra Bharati.

3. With celebrated writer Shawkat Osman

Thus he was always a soul searcher, an exponent of deep emotions. Often his words were like a soliloquy although carefully chosen to capture attention of a certain audience. He was mot definitely a romantic with no intention to shock but only to share his innermost feelings. "It was the heart that spoke in my poems first, and all other factors like society and politics were secondary" he said. Which is why his poems deal with subjective interpretations of love, longing and lonliness and other experiences of life.

'Why did you bring me here father,

In this city of stone?'

The disillusionment and isolation of the urban experience is evident in these two lines and characterise a part of the poet's ethos.

"I was faithful to whatever subject I touched on, even if one reflection contradicted the whole of what I was, I revealed what I felt like revealing" - another reflection of the poet.

The politically unmotivated poet found a way to reach out to the people through verses that tackled subjects like the language movement and most of all the war of liberation in its entire cultural ramification. Instead of slogan-like incantation, he preferred to use an abundance of simple imagery that used nearly verbal dialect as a vehicle. Shadhinota Tumi' perhaps is the epitome of this mode of writing.

The emotional poet who knew how to reach out to touch the soul |

Since his first book Prothom Gaan Dityo Mrittur Aagé (First Song Before Second Death; 1960), Rahman worked consistently on existentialist themes like the absurdity of living in an increasingly uncertain world. Death remained his muse for a long time; and it was during the mass upsurge of 1969 that he incorporated elements of social realism in his poem. Rahman clearly saw the breakdown of the quasi-feudal state of Pakistan and the rise of the toiling masses of this land in the blood-soaked shirt of Asad, a martyr who died in the hands of dictator Syub Khan's army. In Asad's Shirt, one of his poems that fuelled the mass upsurge, Rahman wrote:

Like bunches of blood-red Oleander, like flaming clouds at sunset

Asad's shirt flutters

In the gusty wind, in the limitless blue.

To the brother's spotless shirt

His sister had sown

With the fine gold thread

Of her heart's desire

Buttons which shone like stars…

The poet (centre) was always vocal about his thoughts and open in his actions The poet (centre) was always vocal about his thoughts and open in his actions |

Not only did the poem sow the seed of future of the leading Bangla poet in the last half a century, it has also changed the course of future Bangla poetry itself. From the narrow timid world of existentialism and its made-up crises Rahman had quickly taken out Bangla poem to the wider world, making the plights of the poor of his land his first priority. So it

is not surprising then that two of his major books would be fiercely political in form and style. Both Bondi Shibir Theke (From the Prison Camp; 1972) and Buk Tar Bangladesher Hridoy (Bangladesh is His Heart) take in oppression as a central theme. It was during Ershad's autocratic regime that through his poems Rahman became a people's poet. Lately his poetry veered towards the theme of death yet even when his health was failing he seemed quite comfortable with his recent writings. "I still enjoy it and find no reason to stop." Perhaps that is exactly what his innumerable admirers feel regarding reading his evocative verses that will live long after their crafter's end.

Mask

Shower me with petals,

heap bouquets around me,

I won't complain. Unable to move,

I won't ask you to stop

nor, if butterflies or swarms of flies

settle on my nose, can I brush them away.

Indifferent to the scent of jasmine and benjamin,

to rose-water and loud lament,

I lie supine with sightless eyes

while the man who will wash me

scratches his ample behind.

The youthfulness of the lissome maiden,

her firm breasts untouched by grief,

no longer inspires me to chant

nonsense rhymes in praise of life.

You can cover me head to foot with flowers,

my finger won't rise in admonishment.

I will shortly board a truck

for a visit to Banani.

A light breeze will touch my lifeless bones.

I am the broken nest of a weaver-bird,

dreamless and terribly lonely on the long verandah.

If you wish to deck me up like a bridegroom

go ahead, I won't say no

Do as you please, only don't

alter my face too much with collyrium

or any enbalming cosmetic. Just see that I am

just as I am; don't let another face

emerge through the lineaments of mine.

Look! The old mask

under whose pressure

I passed my whole life,

a wearisome handmaiden of anxiety,

has peeled off at last.

For God's sake don't

fix on me another oppressive mask.

The poet, who has won many accolades, has left behind a legion of admirers |

From: Selected Poems of Shamsur Rahman.

Translated and Edited by Kaiser Haq.

Asad's Shirt

Like bunches of blood-red Oleander, Like flaming clouds at sunset

Asad's shirt flutters

In the gusty wind, in the limitless blue.

To the brother's spotless shirt

His sister had sown

With the fine gold thread

Of her heart's desire

Buttons which shone like stars;

How often had his ageing mother,

With such tender care,

Hung that shirt out to dry

In her sunny courtyard.

Now that self-same shirt

Has deserted the mother's courtyard,

Adorned by bright sunlight

And the soft shadow"

Cast by the pomegranate tree,

Now it flutters

On the city's main street,

On top of the belching factory chimneys,

In every nook and corner

Of the echoing avenues,

How it flutters

With no respite

In the sun-scorched stretches

Of our parched hearts,

At every muster of conscious people Uniting in a common purpose.

Our weakness, our cowardice

The stain of our guilt and shame-

All are hidden from the public gaze

By this pitiful piece of torn raiment Asad's shirt has become

Our pulsating hearts' rebellious banner.

[ Asader shirt (Asad's Shirt) - by Shamsur Rahman, Translated by Syed Najmuddin Hashim]

With Nasiruddin and Sufia Kamal in 1985

Roar, O Freedom

What shall I do with the spring

when I hear only the cuckoo moaning

and cannot see gorgeous flowers blossom?

What shall I do with the garden

Where no birds ever pays a visit?

Oh, how rough and stony is this earth!

Skeletons of trees stand, row after row,

like so many desolate ghosts.

What shall I do with the love

that places on my head a crown of thorns

and hands out to me the cup of hamlock?

What purpose the road serve

On which no one treads,

Where vendors of coloured ice-cream

Or waves of city-inundating processions

are never seen?

I had called you, dearest

When we started our journey

With our face turned to the rising sun.

When the back-pull of bourgeois charm

Rahman receiving the Ananda Purashkar |

Kept from your ears the soaring sound

of the people singing.

You are still prisoner under the claws

of a fierce eagle.

you cannot yet walk on a road

with the rainbow coloured carpet spread on it.

Oh, how tough it is to keep going

without you by my side!

A horrid monster comes, casting dark shadows

all around;

in a moment he crushes under his heels

the foundation of new civilization,

he hangs the full moon on the scaffold,

declares unlawful the blossoming

of the lotus and the rose.

He bans my poems, stanza by stanza,

quietly, without any fanfare,

he bans your breath,

he bans the fragrance of your hair.

By the bent body of the young girl

sitting on the lonely porch of old age.

waiting for the dawn of happy days.

By the long days and nights of Nelson Mandella

spent behind the bars.

By the martyrdom of the heroic youth

Noor Hossain,

O Freedom, raise your head like Titan,

give a sky shattering shout,

tear off the chain around

your wrists.

Roar, Freedom, roar mightily!

Translation: Kabir Chowdhury

Mustafa Zaman, Shamim Ahsan and Aasha M. Amin

(Some of the information has been taken from SWM's cover story on the poet on the occasion of his73rd birthday in 2004, as well as other features in various dailies)

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2006

|