| Cover Story

In Search of our Elusive Constitution

Nader Rahman

So often in Bangladesh we say that the rights of the people have been curtailed, but where is the fact behind that statement? For one to even say that there must be evidence of rights in the first place. Where is that evidence? The answer to that question is that the evidence lies in our constitution, to be precise in Part 1 Chapter III which deals with our fundamental rights. The next question is where is our constitution?

Fake copies of the constitution are being sold in Nilkhet |

That question has been continually raised by Tanbir Siddiqui the founder and president of Change Makers. Siddiqui is a lawyer who has worked with the media sector for over 20 years. After finding the hustle and bustle of media life too superficial to take he decided to change careers. He moved from mass media to activism seamlessly and has never looked back.

In the process of his work he set up Change Makers, which he registered under the Trust Act of Bangladesh. The organisation carries out research and studies on a number of different issues, and recently it has taken to the task of addressing good governance and democracy, human and child rights, safe labour migration, violence and abuse against children and woman as well as human trafficking.

Change Makers considered the Bangladesh constitution an important component of their civic education programme and contacted the ministry of law, justice and parliamentary affairs for copies of the constitution. To be exact they asked for 5000 copies of the constitution, and they even stated that they would pay for them. What happened instead was the law ministry stalled him for a couple of months saying that they were going to print some new copies. They soon found out that it was not going to happen then they applied to the ministry in writing on October 10 2005 to the secretary seeking permission to print 5,000 copies of the constitution on their own. The purpose, distribution policy and relevant issues were mentioned in the prayer. It was also categorically written that those constitutions would be used for the purpose 'civic education among the students for free distribution'. They also presented the examples to the authority that other agencies published the constitution and those were widely used. Moreover, the English version of the constitution is available on the web site of the law ministry.

After much deliberation in January 2006 their prayer was rejected. One of the flimsy but popular arguments the ministry people usually use in favour of not to allowing others to print the constitution is that “if any mistakes are made who will take the responsibility?” Siddiqui says “that is an absolutely stupid and ludicrous argument. There are hundreds of ways to prevent printing errors. Moreover, they can certify the final proof with a signature before final print. I requested them to do so in our case, but they just did not listen”

After continually being brushed aside by the law ministry, Change Makers went ahead and finally printed a booklet titled 'Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh and Universal declaration of Human Rights' in April 2006. Disclaimers were there in the printer's page “this is not a government publication. The liability lies with the publisher if there is any mistake or typographical error. Government printed copy should be read in case of any confusion over the meaning of any article”. They also mentioned that it was 'To be used for civic education programme and for free distribution'. Using the booklet that they printed in April this year they set out for their Civic Education programme and by July they courted major controversy.

The Law minister held a press conference at his office on July 20 '06 and alleged that

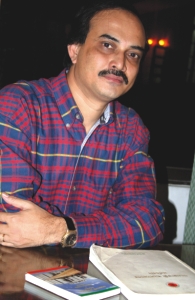

Tanbir Siddiqui |

'some publishers' were publishing the Bangladesh Constitution and selling it, which was apparently a violation of the 'rules of business of the government and copyright law'. Several TV channels also broadcasted the same news in their main bulletins, it had become national news. On the same day the ministry wrote an official memo to the Dhaka Metropolitan Police Commissioner asking him to take stringent action against such publishers. The following day two English and two Bangla national daily newspapers; Daily New Age, The Independent, Daily Jugantar and Daily Amar Desh and on July 22 the Bangla paper Daily Ittefaq published the story quoting the Law minister and the letter written to the police commissioner by the ministry. All the news items mentioned Tanbir Siddiqui's name, his organisation's name and the address of the office and alleged that they were selling the constitution in the market. The press got ahead of themselves without doing basic fact checking, Change Makers never sold a single copy, as they stated in their letter to the ministry their publication was “To be used for civic education programme and for free distribution”. During the press briefing the minister showed Tanbir's publication to the journalists along with other publications (those publications were a carbon copy of the government published document, not Change Makers one). On July 23 the Law ministry even published a public 'Caution Notice' in some leading national dailies prohibiting publishing the constitution in any form (photocopying, scaning) and warned people about the consequences if anybody did so. But Change Makers still had their share of supporters on July 22, in Nagoric Committee (a newly formed civil society movement) meeting criticised the government for not making the constitution available and taking action against Tanbir Siddiqui. Siddiqui's reaction to all this is “The constitution is the people's property, not the government's, people have the right to have the constitution any time, any place in Bangladesh. If the government says that they have the copyright then they are responsible to make it available as per people's demand. NGOs or civil society organisations should also be allowed to print the constitution. Especially when it is for non profit and free distribution for academic, educational, orientation schemes, awareness programmes, the government should encourage them. The ministry should check the final proof to avoid any unwanted errors or omissions.”

Interestingly, Tanbir Siddiqui's inspiration for the programme came from two rather unusual incidents. “when I was last in America I witnessed seasoned lawyers giving up their weekends to teach children between the ages of 5 and 10 about the constitution, how it works and what they could get out of it, that was truly an eye opener for me, there they value the constitution and how it works for every individual person and the age of 5 is not considered too young to start learning. It was truly amazing and inspiring.” With that experience he adds “another situation which I found myself in recently only strengthened my belief in the cause of constitutional awareness and accessibility. Recently a friend of mine asked me for a copy of the American constitution, I didn't have it so I contacted the American Embassy for a few copies. The very next day delivered by special parcel with 'urgent' stamped all over a package I was sent 5 copies of the American constitution! Five copies were sent overnight, they felt it was their duty to provide the constitution to anyone that wanted it, I laughed to myself when I thought about my experiences and what I went through to get a few copies of my own country's constitution. This only gave me more resolve to fight the situation in our country”

But there are deeper problems that need to be addressed; the availability of constitution must be challenged. According to government files the last time the the constitution was published by the state was in 2000 and that too 12,000 copies were made. That paltry number was the largest single printing of the constitution in Bangladesh's history. The Daily Janakhanta even published an article on the matter. It said that after the BNP came to power they destroyed the pervious constitutions printed by the Awami League. And since then the BNP have not reprinted the constitution during their last term, in fact in 2004 the 14th amendment was made part of the constitution and even after that it was not reprinted! This country is currently without an updated constitution!

Change Makers is trying to live up to its name, but with stiff resistance from the powers that be, who knows what will become of such a noble organisation. The truth is in our country the constitution has been mystified, the government (both the previous governments) has tried their best to keep it out of the common man grasp. The rationale behind that move is quite simple, with the constitution comes empowerment and that seem to be the last thing successive government have wanted. As long as people look up to them in awe their power can not be dislodged. There are some simple questions that need to be answered if one is to make sense of the current situation in Bangladesh.

Who is the constitution for, the government or the people? If people want copies of the constitution where do they go? How many copies are printed and what are the distribution procedures? If someone from the villages wants a copy how does he go about getting one from the government? Does the government want to keep the citizens unaware of the constitution and its provisions? And above all, do they have the authority to make the constitution unavailable to the general public? One issue encompasses all of the above: is it reasonable to think that people have to wait to know their “Fundamental Rights guaranteed by the constitution” till the government prints and distributes it among its people? Till then what happens to their “fundamental rights”? These questions need to be addressed and answered.

After it is all said and done the Change Makers programme has been a resounding success, when it can spread its wings and take on wider national coverage is eventually all down to funding. But at least the organisation and its founder have served as eye openers to a nation that has seemingly lost sight.

Early Lessons in Constitutional Rights

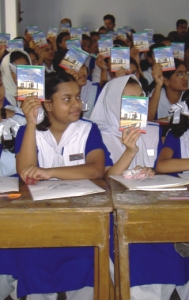

Children at the Government Girls High School in Rajshahi hold up the constitution |

One of the organisation's most influential programmes has been “Institutionalising Democracy in Bangladesh”.

This broadly falls under Change Makers Civic Education Programme for Children. The rationale behind the civic education programme is quite simple to Siddiqui. He says. “Education is essentially for developing professional life. What I am looking for is civic education. Learning about citizens right and duties is essential, but the average citizen knows none of them. The average person needs to be empowered.” And that is exactly what the institutionalising democracy programme has achieved.

During the test period, Change Makers visited 41 schools and madrassas in Rajshahi and Khulna, there, under the banner of institutionalising democracy they went about their education programme. The programme targets children between 13 and 16 and in each school 75 students were put together for the class. It starts off with a questionnaire about the constitution, where some basic questions are asked along with a few tricky ones. This is taken for research purposes to see the level of knowledge regarding the constitution.

After that the real education begins. Siddiqui gives lectures on various parts of the constitution and informs them of their inalienable rights. Rights which they did not know even existed. His lectures are followed by a question and answer session, where students are allowed to ask anything related to the constitution. Before this section he openly encourages the children to ask anything they please, and not to be afraid of what their teachers might say to them later. He even goes as far as to say that if any teacher harasses them over any questions asked, he will take the matter up with the teachers personally.

This gave the students the push they required. Without worrying about the pressure of inappropriate questions they probed into every facet that interested them. When some of the programmes were conducted last year, students were keen to know about the Rapid Action Battalion and how constitutionally correct they were. Questions they would not have dared to ask under normal circumstances. This part of the programme gave Siddiqui the most pleasure “to see the children asking and genuinely taking interest in the constitution, their rights and how it is used.” The question and answer sections proved to be an enormous success, but it must be added it was only a success after the basic principles and some broad ideas about the constitution had been taught to the children.

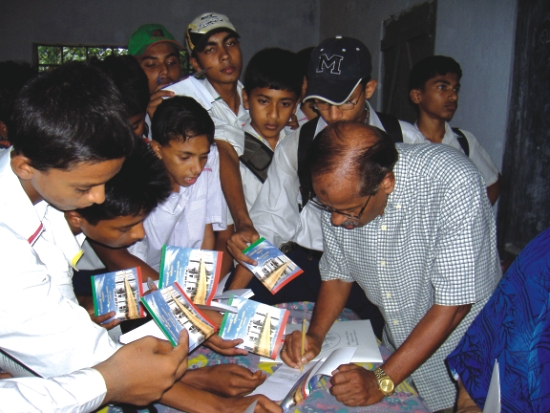

Advocate Enayet Ali signing autographs for students in Khulna

After the question and answer section, the typical schedule demanded that a second questionnaire be handed out. This was the interesting part. Every child received a copy of the constitution and with that a second questionnaire that needed to be filled up at home and submitted back to school. It was mandatory that every child had to answer and return the form. The interesting art was that the questionnaire had questions that could only be answered if the student actually read the constitution. Therefore in order to answer the questions in a way he was forcing the children to read it. Aside from the questions that needed to be answered by reading the constitution, he also put down some questions that could not be answered with the constitution. This he did for a purpose, he wanted the children to include their families and therefore in a small way even make their families aware of the constitution. This social networking was one of the major aims of the programme. Aside from informing the children of their rights and the ultimate law of the land he wanted to empower their families in a small way. He wanted the light of the constitution to shine on everyone.

Now one may rightly ask why is the constitution so important and why do 13 to 16 year olds need awareness of it? Tanbir says, “My focus is on democracy and fundamental rights, their basic mechanisms are found in the constitution." He also adds “I want to create conscious citizens, and that can only happen if they have knowledge. Knowledge in their professions is not enough, they need to know their basic rights. It is only through the use of knowledge that they can move forward. This programme is then basically about empowerment, all I want is to put power back into peoples lives. In a small way my programme achieves that.”

The empowerment comes at different levels, for example these girls and madrassa students were given special attention. The focus on girls is easily understandable, they are quite openly the second sex in this country, any form of empowerment, whether through knowledge of the constitution or other means is a step forward. But it is interesting to note that Change Makers also wanted to reach out to madrassa students, they are often children who are forgotten and generally nothing is expected from them in terms of civic awareness. In fact, Tanbir says, “Some of the best responses and most interesting sessions took place in madrassas, they are very eager to learn and they are very sharp. It was a real pleasure to teach them, they were genuinely interested and have sent me many letters of thanks along with requests to go back and take more in-depth sessions with them.”

Madrassa students were also targeted by Change Makers

The programme was also orientated at 13 to 16 year olds for a reason. Siddiqui says, “Many people asked me why I didn't target a different age group, they claim that 13 to 16 year olds are probably a little too young understand or need the constitution.” He went on to say “13 to 16 is a very important age group because at that age students are relatively clean from politics and soon in their lives they will face the first real test of politicisation of the system and hopefully in a small way I can make them think twice about the decisions they make.” What he was referring to was the fact that after the age of 16 children usually apply to colleges and that is where their first impressions of society and how one should behave in it occurs. The truth of the matter is that to enter good colleges students must usually pay a little bribe or the favours of petty mastaans, associated with different political parties, will be sought. This is when within every student the thought that political parties hold the sole power to help them or that bribes are the end all and be all in life are rooted into their minds. Change Makers hope to fight those stereotypes, Tanbir says. “The ultimate purpose of the education is to teach the children that they do have a choice in life, they need not seek political backing to achieve anything in life, as long as they have the proper knowledge they can fight those situations.” It eventually boils down to the scenario that when faced with that first real predicament a student who has attended his course can without fear try for a decent college, and if he or she has what it takes and is still not admitted to the college they can question the logic behind that decision.

Eager students involved with the programme |

Some interesting data and feedback was obtained from their scheme and it only went to prove how desperate the state of affairs was before the programme started. Of the 41 schools and madrassas that they visited only one person out of the 41 principles had ever even seen a copy of the constitution. The rest of the people had never even seen it, let alone read it. This provided them with even more reason to expand their programmes, but alas, as usual money constraints have been their downfall. In fact after a few of their programmes they received numerous letters from different organisations asking for copies of the constitution with many even asking if the lecture tour could be brought to certain places of interest.

The civic education programme was a run away success. Change Makers has been asked by numerous institutions, universities and press clubs to organise similar events but due to a lack of funding they have not been able to meet their excessive demand. It is interesting to know that the organisation was helped by a small grant from the American Centre/ US Department of State. But aside from financial help many lawyers, journalists, government officials, local government representatives, activists and eminent citizens have taken part in the different programmes and their help and knowledge really made each individual session special.

Advocate Enayet Ali, a member of the Constituent Assembly, took part in many of the sessions; he was indeed one of the star attractions of the programme. In fact, in Khulna, after one of the sessions when the students found out that he was one of the people who framed the constitution they besieged him for autographs. “The sight of dozens of children lining up to have their constitutions signed by Enayet Ali was one of the greatest moments of my programmes, I could not hold myself back, to be honest and even I asked him for an autograph.” said a smiling Tanbir.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2006 |