| Cover Story

Breaking the Musical Status Quo

Hana Shams Ahmed

Farhana Rahman, a 25-year-old school teacher never leaves home without her cell phone. And it's not just because she wants to stay in touch with everyone while she's away. Her Nokia 8800 is loaded with MP3 songs and when she gets bored of them she just switches on her favourite radio station to listen to the new releases of her favourite artistes. “I get to listen to songs that I've never come across before,” says Farhana, “Our musicians are really doing a great job these days.”

Undeniably, in the last five years as new musicians have entered the arena, there has been a rise in record labels and the concept of 'band' music has slowly disintegrated and made way for a much broader spectrum of music genres rock, pop, heavy metal, hip hop, R&B, electronic, fusion folk and many more. The blast of new songs did not manage to erase the old classics from our memories though-they were decorated with modern music, which appealed to the young generation, though not always to good effect. Songs like 'Krishno' rearranged by Habib broke all barriers of age and class and shot him to fame overnight, even among the Bangladeshi diaspora. Companies grabbed this opportunity and produced jingles, which like Nescafe's 'Cholo Shobai' became hits in their own right. The telecom industry is perhaps making the most of the rise in Bangla music from ring tones, caller back tones and TV commercials, there is no end to the promotion of music.

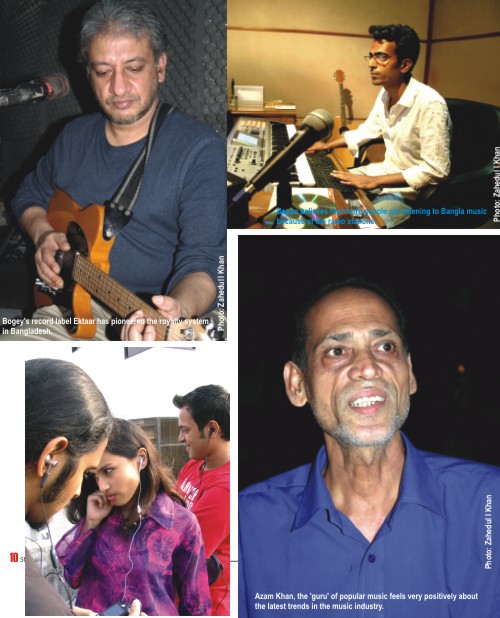

But there is still a certain amount of confusion regarding the term 'band' music as explains Feisal Siddiqi Bogey. Bogey started his first 'informal' band in 1973 but it wasn't until 1985 when he started his band Renaissance that he really got involved with the music industry. He got further drawn in when he founded BAMBA (Bangladesh Musical Bands' Association) and later formed his own record label Ektaar Music in 2002. “Confusion was also created in the west but people there understand these genres more clearly,” says Bogey, “In Bangladesh there is a big confusion between the different genres-contemporary (adhunik) versus pop versus 'band'. James might be considered a contemporary singer and at the same time a 'band' singer. Traditionally speaking, contemporary Bangla songs actually refer to those from 1850 onwards, which of course is not applicable today.”

Sumon, the lead singer of the band Aurthohin talks about the origins of the term 'band' music. Sumon's songs that hits like 'Adbhut Shei Cheleti' and 'Tepantorer Maath' oscillate between pop, rock and heavy metal. “There is actually no such thing as 'band' music,” says Sumon, “About 20/25 years ago there weren't too many bands in Bangladesh. Those that were there used to do cover songs of western bands. Even the ones that were composed had a western influence and people were not too used to them. The songs these bands did were labelled 'band' music. The scenario has changed but people still call it that. Now it's not just bands but individuals who do music of that kind (rock/pop etc) who are also put under the label 'band' music.”

It is a widely held notion that because of the advancement of technology it is possible for practically anyone with a PC and the right paraphernalia to arrange music. “It is true that because of the technology available you are able to close the gap between two singers one being really good and the other being just average, which was not possible before,” says Bogey, “But the more important part of this mass prospect of people becoming musicians is that it's a great leveller. So anybody with a talent is able to move forward because it is not as expensive as it was before. In all kinds of progress there is always a negative side.” Bogey does not think that the digital tricks are substantial enough to make a layperson into a great musician. “No one can write lyrics like Hyder (Husyn),” says Bogey, “Habib (Wahid) uses digital technology which is available to everyone. But no one can become Habib.”

Azam Khan, the initiator of the so-called 'band' music movement with evergreen songs like 'Saleka Maleka' and 'Bangladesh' who can still make his fans go into a frenzy with his stage presence, feels very positively about the trend of rearranging old songs. “It's not always possible to bring back the original feel,” says Khan, “But the good thing to come out of all of this is that the new generation is getting to listen to songs they might otherwise never have heard before.”

One of the most well known voices in the music industry, Bappa Majumder thinks the reason for the huge popularity in rearranged music is the audience's taste. “They were getting bored from listening to the same kind of music,” says Majumder, “As such bands and musicians have tried to come up with different styles of music, and it has been very well accepted by the audience.”

“In some cases it is true that the original songs are getting deformed in the name of remaking or remixing,” says Majumder, “But a lot of musicians are remaking songs in the most brilliant manner. It actually depends on how the work is done.”

Fuad Al Muqtadir, a relatively new entrant into the music industry, who does all his work from his studio in the US, has already managed to make waves with his unique style of electronic music. His latest hit 'Shona Bondhu' from the album Variation No. 25.2 is a hot favourite of joy riders but has also received criticism for its crude lyrics. “I don't care what's socially decent or indecent or what is musical,” says Fuad, “I do a lot of things in the name of good humour. I try to keep it real and not hide behind a facade of cultural decency.” Fuad says that he likes taking risks and portraying what really happens in the world.

“People with little talent have been trying to produce music from the beginning of time (with or without technological support),” says Fuad, “Those who get filtered out become stars and those who get left behind are forgotten. I think the people who put down electronic music and musicians fear their own extinction and are a little defensive about this new era. Their music is repetitive in style and format and they have been re-inventing the wheel for ages. Our generation broke that. Though it is true that anyone with a PC and the right software can generate sounds, but to make music, there is a lot of hard work, technological education and skills necessary. It takes a lot of knowledge in pro audio technology and even physics to be a composer/producer.”

Fuad believes in perfection. “I think to make a perfect album if you have to use any pitch correction device then do it! It's about the overall result. If it's wrong to use an auto-tuner (an audio processor for correcting pitch in vocal and instrumental performances) then it's also wrong to use reverb (the persistence of sound in a particular space after the original sound is removed), or equalise the singer's voice, or to go back and re-record a segment the singer made a mistake on.”

Singer Sahana Bajpaie whose rearrangement of Tagore songs is set to come out this month does not think that remaking changes the original 'feel' of the music. “On the other hand,” says Sahana, “It actually caters to a lot more people than the originals do.” Musician Maqsudul Haque raised a huge amount of controversy when he rearranged a Tagore song five years ago.

DJ Rahat, whose DJ remixes of timeless songs like 'Ashar Srabon' and 'Dakatia Banshi' have replaced western and Hindi numbers on the dance floors of Dhaka, believes that changing the music of such songs appeals to the young generation. “I try to maintain the original 'feel' of the song while changing the music,” says Rahat.

Hip-hop has never been really popular in Bangladesh. But when Stoic Bliss landed their album “Light Years Ahead” with such hit songs as 'Abar Jigai' (used later in a Djuece commercial) and 'Kaka", all the way from the US it crashed into the album charts and hit the Dhakaites in all the right places. “No one actually took a serious initiative to bring forth the genre to the people other than a few rap-parody albums that were released in the early 1990s,” says vocalist Kazi, “I expected the album to become a popular hit among those who listen to hip-hop but I never expected it to be such a huge hit.”

There is a lot of criticism about the hip-hop culture with its use of slang and crude language. To this Kazi says, “Everyone, no matter what age-group they fall under, have used, still use and probably will use slang in their daily lives. It (the slang) is very well embedded in every culture around the world. Therefore, I don't see how using slang is an example of 'anti-culture' when it comes to our own culture. Its just gestures we use with one another to show how we feel. Of course, we didn't want to go all out and use slang to the point it becomes plain vulgar, moreover it's a watered-down version so the listener can get the idea without having us spell it out for them.” Kazi believes that today's generation is very open-minded and are slowly coming out of the 'fixed-box-mindset' mentality.

Although radio is a very old technology, the arrival of the private radio stations (Radio Today 89.6FM and Radio Foorti 98.4FM) has been somewhat of an innovation in the lives of the Dhakaites. With traffic jams being a never-ending woe for city dwellers, the radio is probably the best friend one can have. Md Zahidul Haque Apu, an RJ and Station Producer at Radio Foorti which began transmitting from September 2006 says that when they started most people were sceptical. “Everyone was asking what a radio station could possibly do in the TV era,” says Apu, “Now the scenario has taken a complete u-turn. Everyone has accepted it so much that it has become a part of everyone's lives. It has now become a kind of fashion to listen to the radio.”

Apu believes that more people are listening to Bangla music these days. “Our musicians are doing so many new things. Listeners are getting interested in Bangla music because its quality has improved a lot and radio is just a way to link the artistes and the listeners,” he adds.

According to Bogey radio along with the cell phone industry is a major shift in the music business. “There's a lot of money now in the telecom industry, who are also very closely involved with music,” says Bogey, “Music is the number one item in value added content through the cell phone. Non-stop music is very convenient. And it's true that putting on something specific is a bit of a headache and listening to the radio you are inadvertently forcing yourself to listen to something you wouldn't normally put on and one surprise trends to oneself.”

Azam Khan, who is a big fan of the radio, is not happy that the stations are still centred in Dhaka and hopes that they will increase their frequency and it will spread outside Dhaka. “The presentations from the RJs are fun to listen to,” he says, “They should also make TV presentations as much fun.”

Bappa Majumder another big fan of the radio says that he stays up all night listening to the radio. “I think 'listening' to music is much more gratifying than 'watching',” says Bappa, “I think less people are listening to Hindi music now because of the radio stations. This is a very positive trend for us musicians.”

With the rise in Bangla music, the number of record labels has also gone up. Ektaar music is the proud label of such alternative bands as Bangla and Habib's super hit album 'Krishno'. According to Feisal Siddiqi Bogey, its founder, when Ektaar started there was an underlying thought there was no money to be made from good quality music or the audience was not music-literate enough. “It has been a prevalent thought among many musicians that as far as music is concerned the audience is not in the same level as us,” says Bogey, “We do not subscribe to this point of view. We've always said that the problem with the Bangladeshi music industry is that people are switching off because we are not giving them anything worth listening to. But the lyrics of Nazrul Islam and Rabindranath are still very popular. So in fact, quality has always sold better in Bangladesh.” And indeed good quality songs from Potheek Nobi and Bangla's 'Kingkortobbobimur' have sold like hot cakes, in fact 'Kingkortobbobimur' and Habib's 'Krishno' are still a couple of the best-selling albums in Dhaka and among the Bangladeshi disapora years after their release.

Ektaar is also a pioneer in giving royalties to artistes, which is a norm in all record labels in countries around the world. Royalty ensure that the artiste or band gets his/her rightful share of the revenue earned as it is difficult to predict how well an album will be received by listeners before it is released.

Nazmul Haque Bhuiyan, the proprietor of G-Series, one of the most prolific record labels, does not believe that there is enough transparency to maintain the royalty system. “For each album, my company and the artiste agree on a particular amount, which is a one-time remuneration,” says Bhuiyan, “I am proud to say that every artiste treats the company as his or her own and has a lot of passion for the music itself.” Bhuiyan has now established another record label, Agnibina, which is going to work under the royalty system. “Every sale, downloaded ring tone, television and radio exposure of every song will be montored by an organisation,” says Bhuiyan, “And the money will be shared between the company and the artiste. Once this company starts to work properly and settles down, we will eventually apply similar policies to G-Series.”

Music piracy is one of the biggest problems faced by record labels. It's not just copied CDs that are sold freely in audio shops, especially outside Dhaka, but some websites offer free downloads (polapain.com) of MP3s. Bappa Majumder is very distressed by the effect of piracy on the music industry. “If an album is pirated (copied and downloaded from the Internet), its sale goes down. The production companies lose interest in releasing albums. So they will do less work as a result of which the musicians get affected. And ultimately the listeners suffer.”

According to Azam Khan, the army needs to get involved if piracy is to be really controlled. “The police are too corrupt,” says Khan, “They will just take bribes and let go of the pirated materials.”

A group of record labels and audio companies got together last year and decided to put a stop to this theft. They formed MAP (Musicians Against Piracy) and so far has raided a lot of places all over the country and burned hundreds of thousands of pirated CDs. Ershadul Haque Tinku, a consultant of Impress Audio Vision and the chief co-ordinator of MAP says that piracy has been going on for a long time and it is not possible for a single organisation to do anything about it. “The audio cassette companies didn't do anything about it,” says Tinku, “Even if they took steps they eventually came to an understanding with the perpetrators so eventually no legal action was taken against them.”

“We went to seven or eight different places in Dhaka city and we caught a lot of people red-handed and a lot of organisations came forward when they realised that we were doing some good work,” says Tinku, “The action committee with the help of the law enforcement agency would go to different places and catch the perpetrators in the act. We recovered hundreds of thousands of pirated CDs from different places in Chittagong, Khulna and Feni and burned all of them in the presence of the police and the media including the machinery they use to print the pirated CD sleeves. Many people surrendered on their own, because the police kept harassing them after that.”

Arnob, who got into the music line with the band Bangla and who is now a very successful musician in his own right with the mammoth hit album 'Hok Kolorob' under his belt, thinks that piracy is not as big a problem as it is made out to be. “If there is proper distribution in the places where there is a demand, then piracy will not be necessary,” says Arnob, “It takes time to copy a CD. If the shopkeepers can make the proper profit margin then they won't need to sell pirated CDs.” He points out to neighbouring India and adds, “They have companies who are solely involved with distribution, which does not exist in our country.”

He points out that CDs are sold too cheaply to the customers. “It's not fair to the musicians,” says Arnob, “In a country like India, CDs are not sold below Rs 125 while in our country CDs are sold at Tk 80, 60 and even 50.” Talking about the breakdown of producing a CD Arnob says, “It takes about Tk 30 to produce a CD and Tk 25 if the cover is made of paper. Record labels sell these CDs to the shops at Tk 30. That leaves basically nothing for the artistes.” Arnob says that if the CDs are sold at Tk 100 to the customers, everyone will get a fair share.

Arnob does not believe the media reporting on music is professionally done. “Those who do the music reviews are not musicians,” he says, “One cannot really judge something if they don't know about the subject.”

Feisal Siddiqi Bogey agrees that the reviews are not really informative. “If you read reviews in the magazines, the only comment they can make is that this album has 10 or 12 'melodious' songs in it,” says Bogey. He adds though that the reviewer does not have to be a musician. “We do not look to the media to analyse the music, we want to know how they as a listener are reacting to it,” says Bogey, “Is it well sung? Does it sound pleasant or unpleasant? Are the songs catchy or upbeat?”

Azam Khan is very pleased with the changes in the music industry ever since he started the revolution in the 1970s. “At one point there was a sudden fall in the music industry but I think it's back on its feet and doing quite well,” he says. Thanks to the originators of 'band' music and the consistent hard work of the musicians, Bangla songs are once again on everyone's iPods and MP3 players. And with the help of TV Channels and radio stations, along with the enthusiasm of the telecom industry, hopefully Bangla songs, old and new will forever have a prominent place in the country's culture.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2007 |