|

Perspective

A Diasporic Perspective

Deepa Mehta's Water

Aashna Ali

|

Lisa Ray and John Abraham in the film. |

When the production of Deepa Mehta's highly acclaimed film, Water, first started in 2000, Hindu fundamentalists staged violent protests, finally burning down the set, forcing Mehta to finish her film in Sri Lanka. The film was nominated for Best Foreign Film at the 2007 Oscar Awards. The protests in India became fodder for journalists praising Mehta for her courage, and the extreme nature of the protests allowed many to dismiss them as the hyper-sensitivity of religious conservatives. The injustice portrayed in the film was in fact a product of religious conservatism, but rather than directly targeting it, Mehta may have indicted Hinduism and India's cultural values instead through the use of generalisations; a possible reason for her not finding an audience for an otherwise excellent film in India itself.

A young hero Narayan, played by John Abraham, says to his father, “Do you know, Lord Ram told his brother never to honour those Brahmins who interpret the Holy Texts to their own benefit?” His father tells him that he is not a hero in an epic play, but as the hero in Water, it is this disparity that he was meant to expose. Aimed at a Western audience, the film portrays the power of the deep-rooted traditions of India to generate oppressive practices, exposing the tensions between faith, and the reality of its practice in the daily lives of the faithful. The movie opens with a quote from The Laws of Manu as an example of the religious doctrines that imprison widows, claiming that a widow must suffer until death, restrained and chaste, and that an unfaithful woman is reborn in the womb of a jackal.

|

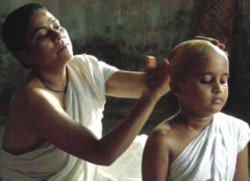

The young Chuyia adjusts to widowhood. |

The film moves on to show the lives that widows must live in ashrams. Old, ailing women live in deprivation and the only young woman there, Kalyani, played by Lisa Ray, must prostitute herself for their survival, goaded on by the authoritarian matriarch of the ashram. A six-year-old, Chuyia, comes into their lives as a young widow and challenges their beliefs with her youthful sincerity.

In reality, life in an ashram can indeed mean begging, eating poorly, sleeping on floors, and at times resorting to prostitution to survive. The serious psychological implications of these conditions as they existed in the 1930s, when the film is set, and do today are brought to light by the misfortune that plagues the widows of Water. The story evokes the rage and empathy of Mehta's viewers and hopes to stir some action.

However, the microcosm of this particular ashram is Mehta's dramatised re-creation of a complicated set of issues in a historical setting. "Films can't provoke change," Mehta said to the Los Angeles Times at the time of its release. "If you're lucky they can provoke a dialogue…I'm a storyteller." Mehta is not a historian, but her reach over the Western public results in the acceptance of her stories as understandable representations of Indian life for the West. The scope of a 117 minute film limits Mehta's ability to create an accurate representation. Though widows do live impoverished, difficult lives, ashrams are not commonly understood to be silent brothels. The practice of putting widows in ashrams is age-old, but its justification through sacred text is not so readily offered in reality as in the film. The Laws of Manu are not laws, but translated as such by the British during their rule, and were intended as teachings about the best ways, as perceived at the time of their creation, to live a decent life.

|

Widows cleansed by the water. |

However, Mehta must deliver nuggets of religious doctrine for clarity, compromising the esoteric quality of texts from which dogmatic practices were constructed. Chuyia is told, “Our Holy Books say that a wife is part of her husband while he's alive. When husbands die…wives half die with them.” A Brahmin says with confidence, “A Brahmin can sleep with whomever he wants, and the women he sleeps with are blessed.” While these beliefs exist, the epigrammatic dialogue makes them seem strictly textual, while some of these beliefs are more tradition than text, or interpretations that have grown into culturally accepted norms. That a large range of texts are often referred to in the film as “Holy Scriptures” rather than specifically identified, renders their quotation problematic, offering sweeping generalisations to a foreign viewer as a portrait of Hinduism.

While Hindu values are accidentally criticized rather than the conservative extreme, secular values are also subtly privileged. A sketchy political sub-plot follows the Indian discourse of nationhood after the arrival of Gandhi in 1938. Characters' comparisons made between Hindu and British ideas of freedom conflate issues of faith with those of nationalism, deepening an already potentially damning portrait of India as backwards to a Western audience.

The limitations of the film fail to acknowledge Hindu texts and their bias towards women as the product of oral discourses of conduct centuries ago. As with all ancient doctrine, they beg logical reinterpretation applicable to India of the 30's and contemporary India alike, but are manipulated under the authority of fundamentalist religious figures towards their own ends. Associating sacred texts and practices with the oppressive nature of colonisation is to reframe India and Hinduism as imprisoning, rather than fundamentalist ideology as a whole, as a universal oppressor. Privileging secularism as the answer in the face of religious and colonial oppression, Mehta accidentally creates the portrait of a country limited by an ignorant faith - a conception of many Eastern countries already widespread in the West.

Deepa Mehta's status as an Indian filmmaker striving to expose the rich culture and practices of India is complicated by her experience as a Canadian-educated, diasporic filmmaker. The world-view generated from a Western education interpreting Eastern problems easily succumbs to the human tendency to over-simplify the perceived “other” and therefore perpetuate large, damning generalisations. As an Indian, Mehta's intentions are not to objectify India or dishonor Hinduism, but she too is imprisoned by her internalized filters of interpretation and the constructs to which she must adhere to tell her story effectively within the limits of a 117 minuets film, catered to the perceptions and judgments of a Western and primarily secular audience.

Mehta is one example of the many South Asian expatriate artists in the West whose art is important for the exposure of the West to the East, regardless of the possible subtleties. South Asian filmmakers and writers are often controversial. Mira Nair treated conceptions of unmarried women in a culture very concerned with marriage, and instances of domestic sexual abuse in Monsoon Wedding. Deepa Mehta's Fire also caused a stir for its homosexual overtones. Salman Rushdie fueled tempers until he was exiled with The Satanic Verses, and along with him, Arundhati Roy, Anita Desai, Kiran Desai, Micheal Ondaatje and many others struggle to expose problems while simultaneously celebrating diversity and the ever-changing subtleties of cultural exchange. At times they offend, and at times they don't. The growing number of diasporic artists allows for public access to multi-faceted perspectives of similarly multi-faceted cultures, but it must also be remembered that artists are forced to work within the confines of their media, which do not always allow for thorough representations and are therefore also forced to tread the very fine lines of social, political and religious tempers worldwide.

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2007

|