|

Book Review

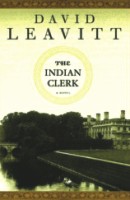

Leavitt Computes

the Nature of

Attraction

Sharon Dilworth

My understanding of math, admittedly very imperfect, is that the field advances incrementally with mathematicians' existing knowledge through repetition and formulaic review. My understanding of math, admittedly very imperfect, is that the field advances incrementally with mathematicians' existing knowledge through repetition and formulaic review.

In his new novel, David Leavitt not only describes this world, but also captures its timelessness and transcendence. Abstract numbers speak a language that, paradoxically, is the only thing the characters can hope to manipulate.

This novel is brilliant. It is a beautiful and creative work that manages to portray a melange of the literary, historical, romantic and academic, with breathtaking prose and deeply nuanced characters.

The novel opens in Cambridge University in the years before World War I. Thirty-seven-year-old G.H. Hardy, considered the greatest mathematician of his day, works diligently on his numbers theory and his mathematical analysis.

He is one of the elite Apostles -- an intellectual, secret society, but his comfortable and predictable life is interrupted by a letter from an account clerk in Madras full of wild theorems unsupported by any proof, yet intriguing in themselves.

After correspondence and considerations, he invites Srinivasa Ramanujan to come to Cambridge to work with him.

Like a mathematical proof, the characters develop one postulate at a time. Hardy's personal relationships and emotional development are initially stunted. Anything that interrupts his work is not just a bother, it's a burden.

He denies the existence of God but is haunted by a former lover who committed suicide when he ended their relationship. Years later, he will admit that his association with Ramanujan was "the one romantic incident in my life," while admitting in the next breath that he barely knew the man.

Also electrified by the Indian clerk is Alice Neville, who travels with her husband to India to bring Ramanujan to England. Her obsession with the Indian clerk begins with India and its exotic differences, which she witnesses with a passion she hasn't felt before. Her unfulfilled longing for this man replaces the love she had for her husband.

Leavitt strikes a perfect note in the character of Alice. Our understanding of Orientalism is usually rendered from the male point of view but, in presenting it from the female perspective, Leavitt strips it of its cliched sexuality and concentrates on the desire of dissimilarity.

In the end, it is Ramanujan who remains the enigma. Unlike his colleagues who believe in their own rational intellect, Ramanujan readily admits that his mathematical proofs come to him in dreams or sometimes "the formulae are inscribed upon his tongue by a deity."

Derisively nicknamed the "Hindu calculator," he becomes gravely ill. Even his illness is a mystery that no doctor can solve and eventually he returns to India, haunting Cambridge long after his departure.

Leavitt understands the novel as exploration, and while he has many native gifts, it may be this adventuring that elevates his work and sets it apart.

Here, his scope and research seems limitless. His prose resonates with supreme authority. And while "The Indian Clerk" could have been merely the story of two men struggling with the concept of infinity, Leavitt extends the narrative to include the characters' struggles with a problem we all share:

How to negotiate happiness when it is interdependent on the desires of others?

Incrementally, Leavitt seems to suggest, is one solution.

This review first appeared in The Pittsburgh Post Gazette.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2007

|