| Cover Story

Kajalie Shehreen Islam

A father complains that no matter how many times he asks his daughter to say “kheyechhi” after she has eaten something, she insists on saying “khaisi”. A grandmother is appalled when the grandchild she has been teaching to speak in formal Bangla suddenly says the word “jibla” to indicate the tongue. A teacher is shocked to hear one of his students describe her holiday as “fatafati” and “jhakanaka”. Listeners shake their heads and cluck their tongues at the reporter saying “satrosatri” on television. A school-going girl wonders where her friend has picked up a foreign accent of Bangla when the friend has never been abroad for longer than a one-week vacation.

For a nation in which people gave their lives for the right to speak in our mother tongue and for it to be established as the State language, today we seem rather confused. Is the Bangla language under threat? Is it being abused, undermined or just neglected?

It is generally accepted that the mother tongue is a language learnt naturally. True, but, like any other language, the mother tongue is also picked up from hearing it being spoken around a person. It is human nature to learn from example, from role models we consider appealing, be it a parent, sibling, teacher or media celebrity. From a very young age, we unconsciously begin to imitate gestures, mannerisms, etc. of people we like. The same applies to language. We learn to speak the way people around us speak. But with so many different influences on us -- family, friends, teachers, colleagues, radio, television -- how do we know which to follow? Unless one form is made to seem more positive, more popular and more powerful than all the others.

|

Pride in one's mother tongue needs to be instilled at an early age. |

The saying goes that a lie told repeatedly eventually becomes the truth. Discourse theory states that power produces the dominant discourses in a society, which in turn establish truth and knowledge in that society. Thus, the “mangled” Bangla that we speak today, if we are allowed to continue, may just become the everyday Bangla of tomorrow.

|

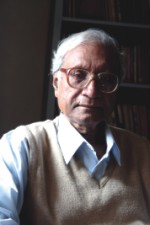

| Professor Serajul Islam Chowdhury |

According to eminent educationist Professor Serajul Islam Chowdhury, the trend of undermining Bangla may or may not be deliberate, but there is an arrogance regarding the proper learning of the language, with many people believing that they do not need to know the language or to practice it in its correct form.

“A capitalist class which has no concern for culture has set this standard and makes it seem right and that there is no need to learn otherwise. The media then imitate it,” says Professor Chowdhury. “The media should not encourage this degraded, insulting and vulgar use of language. They must create awareness by setting a proper standard. Language is not only a reflection of culture; it must follow a standard.”

“Literature is not about physical realism,” says Chowdhury, in response to the claim that the media -- which has come under attack for the use of informal, improper or just incorrect Bangla in recent years -- only reflects, among other things, the language spoken in society today. “There must be philosophy and idealism because it is on these that creativity is based.”

Language changes and evolves, but it does so naturally, over a long period of time, not in a few years because it is imposed upon by a section of society. What percentage of the Bangladeshi population really speak the language we hear on television or on the radio? Most people speak in their own dialects, or a formal or informal Bangla with hints of a regional accent. But looking around us, we think that the way we speak and the way people on radio or television speak, is how everyone in the country speaks.

|

| Professor Abdullah Abu Sayeed |

“We assume that the young generation talk in this manner,” says Professor Abdullah Abu Sayeed, founder of Biswa Sahitya Kendra, of the heavily accented and mixed Bangla used by radio jockeys on private radio stations. “This may not be true, and even if it is, should we support this low taste, or should we teach them by setting a positive example?” The media is a civil society organisation, says Sayeed, which can enrich, enlighten and give direction to people and it must take on this role.

Some people claim that it is not natural to speak in proper, clipped Bangla in their everyday lives. But, says Professor Sayeed, the language of the home is not the language of literature. “A man may wear a lungi at home, or not wear a shirt, but once he steps out of the house, from the private to the public realm, he is expected to dress in a socially accepted and respected manner. The same goes with language. You can speak any way you want with your near ones, but literature, art, has a separate language, a standard which must be followed.

“When Bankim Chandra Chatterjee began to write for a greater audience, he had to raise his standard of language from 'Syambajarer Sosi babu' to one that was acceptable to the whole nation,” says Sayeed.

That does not mean that dialects will not be spoken. “Dialects add vibrancy to a language, helping to depict the unique character of people from different regions. But if a university-educated Dhaka youth is shown to speak in a Noakhali dialect or in a mixed accent, it becomes contradictory,” the professor notes.

|

| The Amar Ekushey Boi Mela which takes place every year reflects

Bangladeshis' love for books. |

An overall degeneration of culture, values, sophistication and language is apparent in our society, says Sayeed, where anyone speaking in formal Bangla is ridiculed for being uppity, as if informal, improper Bangla is what is right.

|

Progga Laboni |

Television personality Progga Laboni finds the quality of language being used on television these days as “absolutely disgusting”.

“Television is a formal medium and not just anyone can appear on it. In the past, there used to be a lot of screening and scrutiny before people could make it on television. But today, all that matters is one's looks and people become stars after doing just one or two programmes,” she says. “With a few exceptions, most do not give their work the time and seriousness required and they hardly know what they are really doing, let alone in what manner they are speaking. In our time, we used to have to write and learn the script; today, it is simply read out from a teleprompter.”

Many people in the media today have no training, says Laboni. Neither is there any accountability. “They make mistakes and then they establish them as being correct.” As for the informal Bangla used in television dramas, she says “I am vehemently opposed to it. It is not a language spoken by anyone and only those who do not know the language properly themselves can encourage such use.”

Actor Asaduzzaman Noor believes this sort of language is used in the media because performers these days do not know how to speak in proper Bangla and it is quicker and easier to get them to say a dialogue in an informal style.

“This is not a reflection of reality,” he says, “because this is not a language that anyone actually speaks. This language has no character and a culture cannot grow based on it. Art is a rich form and its language must be rich as well.”

But, believes Noor, this is only a passing phase. “It is like the advent of satellite television, which brought on the influence of foreign media and changed everything for some time. But people always come back to their own cultural roots,” says Noor. “Eventually, people got tired of it and when local channels went on the air, they turned to them. Similarly, people will go back to the original, proper and rich form of Bangla. Language will change and evolve, but at it's own pace. It cannot be forced. People won't accept it if it is. This trend is a product of commercialism and it won't last forever.”

Film director Mostofa Sarwar Farooki, the instigator of much of the purity debate for having used colloquial Bangla in popular films like Bachelor and television serials like “Ekannoborti” and “69”, claims that he only portrays reality.

|

A huge billboard in the city advertises Farooki's new TV serial "420". |

“I use 'metropolitan colloquial' language in my films and videos based on people living in Dhaka for the same reason that a kooli cannot be depicted dressed in an expensive suit -- simply because film as an art requires truthful portrayal of details. The costume, the performer, the actions, the locations and the language have to look and sound real. By this I don't mean that everyone in every situation speaks in metropolitan colloquial or that no one ever speaks in standard Bangla. We mix it up a lot and this is reflected in my works. If there is nothing wrong with using Kushtia dialect for a story based in Kushtia, why should it be wrong to use metropolitan colloquial in a story set in Dhaka?”

This colloquial is not the reality of an upper middle class as is claimed by many, argues Farooki. “Those who think it is should go out to places like Nakhalpara, Mirpur, Mohammadpur, Rayerbazar, Azimpur, Gopibag, Sayedabad, the Dhaka University halls, Dhaka College, City College, Tejgaon College and talk to the people there.”

Every young generation has their own jargon, he claims, and this is simply reflected in his productions. “And just for the sake of argument,” says the filmmaker, “even if one person speaks in that language, why should the media not show it? Don't minorities have the right to be represented in the media? Or is it all about the majority?”

Farooki does not view film as an educational force and points out that the function and characteristics of news and talk shows should not be confused with that of film as an art. “The former deal with formal language and the latter with both formal and informal language.”

|

In the race to do well in more "useful" subjects at school, Bangla is often neglected. |

With regard to how much responsibility a filmmaker has to keep the masses free of the influence of so-called “bad language”, Farooki says, “Not an iota! It is not the filmmaker's responsibility to put 'good language' on the lips of someone who actually doesn't speak it. Just as it is not his or her responsibility to infuse good attributes to the characters of Golam Azam or Hitler. If that were so, we would have had to chop off several dialogues, characters and even plots from many world-class novels, films and paintings.”

Media effects research has found that the portrayal of violence or other negative behaviour may encourage the audience to imitate it, especially if it is shown as positive and glamorised. If the actions are shown to have negative consequences, however, it will act as a deterrent. But, according to Farooki, the language he portrays in his works is not something he considers “bad” and so he does not feel the need to depict it in a negative manner. “People who are afraid of the future of Bangla as a language should shift their attention to the invasion of English and Hindi, not our very own diversified Bangla.”

In a society where a whole generation of youth have come to be referred to as the “djuice generation” (in reference to the particular jargon used in advertisements of a cell phone package meant for young people), however, it is difficult to deny the powerful role of the media as an agent of socialisation. For parents whose children are growing up exposed to “habby joss” “jhakkas-jhakanaka” “jotil prem”, the onus falls largely on the media and its heroes to set an acceptable standard of language from which their children can learn.

The media are not the only ones to be blamed, however. After the boycott of English for a time, it was found to be an important tool for survival in the outside world and, for many, bringing English back has meant Bangla fading into the background. Even children who have lived abroad all their lives sometimes know better Bangla than children who live here, because they are sent to Bangla schools to learn the language, and parents make a conscious effort to teach them and keep alive their mother tongue. But in Bangladesh, Bangla does not seem useful enough and, in our busy lives today, other interests and forms of entertainment seem much more exciting than reading a book in any language.

Elora Karim, a student of an English-medium school in Dhaka, does not do as well in her Bangla language course as she does in the others. She feels that reading can improve her own writing, but she would rather watch television than read a book. Her mother worries about her daughter not only because her grades on average come down because of this, but also because she will have to live in this country and needs a basic knowledge of the language in order to function in society.

|

| A tribute to the martyrs of the Language Movement. |

But in English medium schools, Bangla is more an occasion-based language, with students singing and cultural functions organised for Victory Day, Independence Day or Ekushey February. Daily lesson plans treat the language like any other subject, if not with even less emphasis on in-depth learning. Libraries lack resources, with little to encourage students to read Bangla books beyond class texts. In some schools, students are not even allowed to speak in Bangla, while some were even known to have fined pupils for doing so. In the race to get top grades in board examinations in mathematics, science and commerce subjects, learning languages is not a priority for most students. The curriculum itself is designed by foreign boards which does not emphasise on languages as the mother tongue but as any other foreign language course for students. Thus, in most English-medium schools, Bangla is simply a language course they need to pass with minimum marks.

|

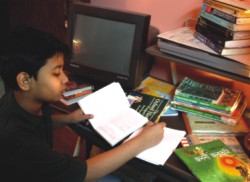

Reading is important for the intellectual and creative growth of children. |

“You cannot do this with the mother tongue,” says Professor Sayeed. “It is the language in which a person thinks, in which their creativity develops. If a person does not know their own language properly, no matter how talented they are, they will not be able to get very far in life. They will not be good writers or politicians or entertainers or anything else. The creativity of a whole nation will be ruined if emphasis is not placed on their learning their mother tongue properly.”

English medium schools can make the Bangla course worth 200 marks instead of the usual 100, suggests the professor. Most importantly, children must be encouraged to read, by which they will become enlightened and hopefully a snowball effect will occur in which they will enlighten those around them, he says. Biswa Sahitya Kendra plans to introduce a Bangla book-reading programme in English-medium schools.

People, especially children, need to be taught to appreciate their language and culture. In schools, special emphasis should be placed on Bangla language courses as the mother tongue and not just a course that needs to be gotten over with. Educational programmes in the media such as television show “Sisimpur” can teach children the basics about language -- the alphabets, names of fruits, animals, and a host of other things, in a way that makes learning fun. Children should also be encouraged, even given incentives, to read good books outside of the school syllabus, as this is important for their intellectual and creative growth. A love of language and culture and a thirst for knowledge should be instilled in them at a young and impressionable age, before they are exposed to the commercial values of the society.

The struggle for the preservation of language must be carried out on many fronts. While the media play a considerable role in setting standards and trends, the family and the education system still function as the first and most basic sources of learning. Speaking or studying in English or any other language is not a problem, but the lack of grounding in one's own language is, and this limitation affects people throughout their lives. Language will change and grow, new words acceptable to the majority will be added to it, but this is a natural process and cannot be forced or hurried or based on an artificial culture. A conscious effort must be made to respect and learn the standard language and enrich one's knowledge of it, for language is the most important tool of communication and means of creative expression.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2008 |