|

In Retrospect

An Indian Patriot, Diplomat and Orator

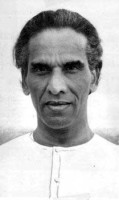

VK Krishna Menon

Azizul Jalil

“Krishna was fiercely dedicated to his country's interest and he sought to protect it, advance it, and project it with an incisive mind which was most elegantly furnished with a fine tapestry of wisdom and wit. It was this mind which he dedicated to the cause of our country, both prior to Indian Independence and subsequently in the councils of the world where Krishna's name attracted immediate attention and respect.”

P.N. Haksar on All India Radio

Haksar, then secretary to the Indian prime minister, and planner and architect of the Bangladesh campaign in 1971, made the above remarks on the day Vengalil Krishnan Krishna Menon died in Delhi on 6th October, 1974. An ascetic person with a brilliant intellect, an abrasive personality and wry wit, Menon was a dedicated socialist. Before India's independence in 1947, he lived many years in London as the secretary of the India League-- working tirelessly for promoting the just demands of India. He had friendly relations with the top British Labor party leaders and intellectuals like Harold Laski, Bertrand Russel and Sir Stafford Cripps, who were also associated with the India League.

VK Krishna Menon |

Menon had a say on the future shape of India through his influence over Nehru and Mountbatten. From Stanley Wolpert's biography of Nehru, we learn that even before he left London in March 1947 to become the Viceroy of India, Mountbatten had the benefit of detailed briefing by Menon. He also carried with him to India a partition plan given in Menon's own writing. Aware that Menon was a window to Nehru's inner thinking, Mountbatten, as well as Labor Cabinet members, gave a lot of weight to his views. Interestingly, Menon had a realistic assessment of the political realities in India and advised Mountbatten to accept Jinnah's demand for 'Pakistans' as Muslim 'homelands' in the western and eastern parts of India. However, these must be limited to those areas where the Muslims were predominant and where the Muslim League had won an appreciable majority of seats. The Western Pakistan he suggested to Mountbatten to accept would include the Muslim-majority districts of Punjab, together with Sind, allowing an approach to the sea at Karachi. According to Menon's plan, Bengal required to be partitioned. His East Pakistan would consist of Muslim districts of Eastern Bengal. He insisted that Calcutta must go to India's West Bengal but recognised East Pakistan's need of a port. Since Chittagong was then tiny and undeveloped, Menon was ready to offer “however many millions it may cost” to develop it.

Wolpert has a lot to say about Nehru's close friendship with Menon. There were many people, who strongly resented Menon's proximity to Nehru and became his enemies. Even though Nehru had to fire Menon from the cabinet due to domestic and US pressures, he was the only person outside the immediate family who was invited to Nehru's seventy-third birthday breakfast. Nehru wrote, “This is of course not a parting, as both you and I are dedicated to serve our country in whatever position either of us may be placed.”

From our school days in Calcutta in the nineteen-forties, Krishna Menon was a hero to us because of his valiant and selfless efforts in the UK for obtaining support for India's independence. Naturally, when I had the opportunity to see him in 1946 at a meeting at the Wellington Square, Calcutta, I was very excited. His spirited speech, delivered in English, to protest against the trial of the Indian National Army officers was impressive. So was his attire-- a fine black suit with a rolled English umbrella, which he used for rain and sun and as a walking stick. Later as a university student in London, I saw him twice in 1955 when he accompanied Pandit Nehru, then prime minister of India.

In one of these occasions, responding to an address of welcome by the secretary of the Indian Students' Association, Menon bluntly told him that it was 'read without comma, without punctuation'. He snubbed the student for raising a host of demands but not mentioning a word about one's own responsibility. That was typical of Menon-- he was often tactless when dealing with individuals. He did not suffer fools easily. Kushwant Singh's book 'Not a Nice Man to Know' has an article “My Days with Krishna Menon”, in which he has written about his experience in the Indian High Commission in London while serving under Menon. He has many uncomplimentary remarks about his boss's attitude and personal behaviour with others, particularly the staff. There is a story about his conversation with a distinguished ambassador on the importance of animal protein. The ambassador who favoured eating of meat said to Menon, a vegetarian: 'After all God has created these animals for human beings.' Menon retorted: 'But your Excellency, God has also created human beings and we do not approve of cannibalism.' Menon, a life-long bachelor, lived a frugal, simple life in one room in the India League office. He did the same later as India's High Commissioner in London, forsaking many of the luxuries that his position entitled him. His friends said Menon lived on tea, toasts and discussions.

Born in 1897 in Calicut, Kerala, Krishna Menon studied at the London School of Economics and was called to the English bar in 1934. He joined the Labour Party and was elected borough councilor of St. Pancras, London for many years. Only he and Bernard Shaw were conferred the Freedom of the Borough. He also worked as editor of Penguin and Pelican paperback books. From the time of the independence of India in 1947, he served as the High commissioner to the United Kingdom for five years. During 1952-62, Menon led the Indian Delegation to the United Nations. He vigorously pursued India's policy of non-alignment and voiced strong support for admission of communist China in the UN. Western diplomats at the UN were irritated and dubbed him 'anti-west', 'fellow traveller' and even 'the old snake charmer.' A great orator, he delivered an eight-hour speech on Kashmir at the Security Council- creating a record for the longest speech delivered there. In 1957, Menon became the minister of defence in the Indian cabinet. He had to leave that position when India suffered a debacle at the hands of the Chinese during their military incursions into India in the North East in 1962. Krishna Menon's was a controversial career but to many he will remain a brilliant and enigmatic politician, remembered for all he did for India and his sacrifices for its cause.

Azizul Jalil writes from Washington.

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2007 |