| Art

Aasha Mehreen Amin

The grandeur of a large-sized canvas can only be justified by strokes that have years of experience and abundance of creative genius. These two virtues -- experience and an overflow of talent can best describe the artist Nurul Islam. Now in his seventies, Islam has had the privilege of being part of the most renowned batch of artists from Bangladesh and being appreciated by the most exacting of critics at a time when few Bangalis, especially from East Bengal, had the opportunity to expose their work. He has also had the misfortune (apart from a few sporadic exhibitions) to be virtually forgotten in his home country despite being one of the most senior and undoubtedly superior artists. Was it the struggle to support six children and an ailing wife that distracted the painter into more practical occupations or was it plain neglect from the bigwigs of the art circle that led to such virtual obscurity, is indeed a mystery. Perhaps it is the result of both. Which is why the upcoming exhibition of this reticent artist who speaks through his paintings, at the Bengal Gallery, is sure to take art aficionados by surprise. The grandeur of a large-sized canvas can only be justified by strokes that have years of experience and abundance of creative genius. These two virtues -- experience and an overflow of talent can best describe the artist Nurul Islam. Now in his seventies, Islam has had the privilege of being part of the most renowned batch of artists from Bangladesh and being appreciated by the most exacting of critics at a time when few Bangalis, especially from East Bengal, had the opportunity to expose their work. He has also had the misfortune (apart from a few sporadic exhibitions) to be virtually forgotten in his home country despite being one of the most senior and undoubtedly superior artists. Was it the struggle to support six children and an ailing wife that distracted the painter into more practical occupations or was it plain neglect from the bigwigs of the art circle that led to such virtual obscurity, is indeed a mystery. Perhaps it is the result of both. Which is why the upcoming exhibition of this reticent artist who speaks through his paintings, at the Bengal Gallery, is sure to take art aficionados by surprise.

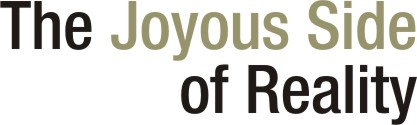

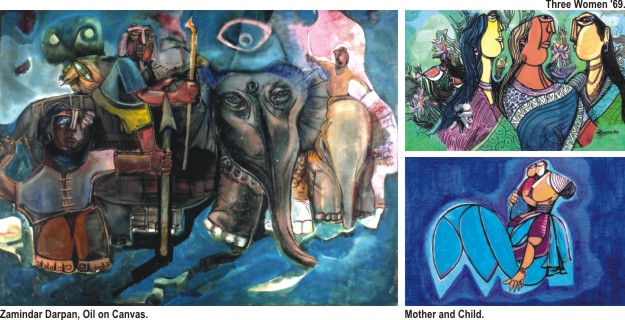

It is with awe that one can take in the sheer magnificence and richness of Islam's works which are all on big canvases and invariably doused in vibrant hues. Being completely obsessed with folk motifs, Islam recreates the seductive beauty of rural life giving it a voluptuous sense of grandeur as well as incorporating the magical realism of folk legends and tales. The paintings in oil especially those that are representative of a majority of his works, are stylised with extreme detailing in form and colour.

Zamindar Darpan, a spectacular piece with its larger-than life motifs that typify Islam's work, is a huge oil on canvas depicting the age-old struggle of the poor against the oppression of the wealthy landlords. It is the landless farm subjects of a feudal system who have revolted against the tyranny of the zamindars. They appear stronger, more powerful and larger than the landlord's lackeys. Riding on elephants the two sides face each other. The expressions are telltale of what will be the outcome of this battle; the landless look weary yet resolute, while the landlord's soldier has the typical arrogance and cruelty that wins in the short run but will lead to inevitable defeat.

While Islam's oils hardly fail to spellbind with their hugeness and gush of colour, his intricate detailed pen and ink drawings are striking in their subtlety and sophistication. Then there are his translucent watercolours (line and colour), which have his signature semi-abstract preoccupations where forms are well defined, exaggerated and constantly merge into each other. Islam's oils exude serenity and richness while his watercolours and pen and ink drawings demonstrate fluidity, movement and complexity of the human form and psyche.

The artist admits that he has always been inclined towards stylized forms and has been influenced by his favourite artists such as Jamini Roy, Qamrul Hasan and Nandalal Basu.

Well-endowed women predominate his works symbolising the fertility, blatant beauty and vitality of rural Bangladesh.

Islam's first solo exhibition and incidentally the first time a Bangali artist was exhibiting solo, was held at the East Pakistan Arts Council (now Shilpakala Academy) in 1964. The exhibition was inaugurated by the then Speaker of the East Pakistan Assembly, Abdul Hamid Chowdhury, father of Abu Said Chowdury, Bangladesh's first president.

Many other dignitaries who had come to Dhaka for the opening of the East Pakistan Television House attended the exhibition. This included the famous Pakistani poet, Faiz Ahmed Faiz whom Islam met. The poet later helped him to get a job as senior artist at J. Walter Thompson, an advertising firm in Karachi where Islam worked for about a year and a half. This stint abruptly ended with the Pakistan-India war that broke out in '65. Islam's temporary joblessness gave him the opportunity to devote himself exclusively to painting specialising on his favourite theme- rural Bangladesh, a subject that seemed to capture the art lovers in the Pakistani art scene. In late 1966 he was appointed as director of The Gallery, a gallery in Karachi. There were few customers those days and the job gave Islam plenty of time and space to paint. It was at this gallery in 1970 that he held another exhibition where almost all his paintings were sold.

The same year, Islam had to rush back to Tangail, to his village home, after receiving news that his father was gravely ill. A series of events kept the artist away from his life's passion. In March 1971 when the War of Liberation broke out, Karatia, Islam's home village was torched to the ground by the Pak Army. In April the artist's father Al-Haj Mofiz Uddin Ahmed died. Sometime later, after Islam and his family had gone back to Dhaka, the Pakistani Army picked up the artist. One of his exhibition brochures had carried the picture of a painting where the artist had written 'Amar Ma, Amar Baba, Amar Bhai, Amar MaBangladesh' and this seemed enough proof of Islam's disloyalty to the Pakistani government. Thankfully, an influential friend helped to get Islam's release in two days. But those two days decided Islam's next move. After leaving his wife and children at another friend's house, Islam left for Barisal to join the Mukti Judho. While he did not actually take part in the fighting he risked his life by delivering secret messages of the Mukti Bahini or working in the camps.

In 1972, Islam joined Interspan (Now Interspeed) as Art Director and the next year started his own firm Rupam Advertisers as well as a press called Karunik Mudrayan. Art continued to take a backseat for Islam who had six children and a wife to support; the business too, was not doing well.

In 1975 Islam had to face another trying turn of fate. The country was in a grip of terror and uncertainty after the assassination of Bangabandhu and the subsequent killing of the four leaders in jail. Islam's wife, Zobaida Islam fell ill and became partially paralysed, a condition she has had to bear for the last 25 years.

Despite financial hardship and personal tragedies, Islam has continued to paint and has accumulated a huge treasury of remarkable works, a portion of which will be shown at the exhibition. Unfortunately for senior artists like Islam, the cost of holding an exhibition often becomes an unnecessary deterrent. Apart from the commission on sales, galleries often do not pay for the framing or for printing the brochures. The present exhibition from June 7 to 18 at Bengal has been partially sponsored by City Bank.

Islam's paintings recapture the magic of old folk tales and celebrate the joy and lust for life that is so much part of our rural landscape. One can only hope that there will be many more such exhibitions to showcase such spectacular work.

East Pakistan Arts Council (now Shilpakala Academy) in 1964. The exhibition was inaugurated by the then Speaker of the East Pakistan Assembly, Abdul Hamid Chowdhury, father of Abu Said Chowdury, Bangladesh's first president.

Many other dignitaries who had come to Dhaka for the opening of the East Pakistan Television House attended the exhibition. This included the famous Pakistani poet, Faiz Ahmed Faiz whom Islam met. The poet later helped him to get a job as senior artist at J. Walter Thompson, an advertising firm in Karachi where Islam worked for about a year and a half. This stint abruptly ended with the Pakistan-India war that broke out in '65. Islam's temporary joblessness gave him the opportunity to devote himself exclusively to painting specialising on his favourite theme- rural Bangladesh, a subject that seemed to capture the art lovers in the Pakistani art scene. In late 1966 he was appointed as director of The Gallery, a gallery in Karachi. There were few customers those days and the job gave Islam plenty of time and space to paint. It was at this gallery in 1970 that he held another exhibition where almost all his paintings were sold. The same year, Islam had to rush back to Tangail, to his village home, after receiving news that his father was gravely ill. A series of events kept the artist away from his life's passion. In March 1971 when the War of Liberation broke out, Karatia, Islam's home village was torched to the ground by the Pak Army. In April the artist's father Al-Haj Mofiz Uddin Ahmed died. Sometime later, after Islam and his family had gone back to Dhaka, the Pakistani Army picked up the artist. One of his exhibition brochures had carried the picture of a painting where the artist had written 'Amar Ma, Amar Baba, Amar Bhai, Amar MaBangladesh' and this seemed enough proof of Islam's disloyalty to the Pakistani government. Thankfully, an influential friend helped to get Islam's release in two days. But those two days decided Islam's next move. After leaving his wife and children at another friend's house, Islam left for Barisal to join the Mukti Judho. While he did not actually take part in the fighting he risked his life by delivering secret messages of the Mukti Bahini or working in the camps.

In 1972, Islam joined Interspan (Now Interspeed) as Art Director and the next year started his own firm Rupam Advertisers as well as a press called Karunik Mudrayan. Art continued to take a backseat for Islam who had six children and a wife to support; the business too, was not doing well.

In 1975 Islam had to face another trying turn of fate. The country was in a grip of terror and uncertainty after the assassination of Bangabandhu and the subsequent killing of the four leaders in jail. Islam's wife, Zobaida Islam fell ill and became partially paralysed, a condition she has had to bear for the last 25 years.

Despite financial hardship and personal tragedies, Islam has continued to paint and has accumulated a huge treasury of remarkable works, a portion of which will be shown at the exhibition. Unfortunately for senior artists like Islam, the cost of holding an exhibition often becomes an unnecessary deterrent. Apart from the commission on sales, galleries often do not pay for the framing or for printing the brochures. The present exhibition from June 7 to 18 at Bengal has been partially sponsored by City Bank.

Islam's paintings recapture the magic of old folk tales and celebrate the joy and lust for life that is so much part of our rural landscape. One can only hope that there will be many more such exhibitions to showcase such spectacular work.

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2008 |