'Our

past has become unpredicatable'

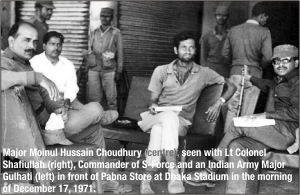

Major

General Moin-ul Hussain Choudhury, was the

Company Commander of Second East Bengal

Regiment and eventually became a Battallion

Commander of the same regiment that captured

Akhaora from the clutches of Pakistan Army

early December 1971. A valiant freedom fighter

and passinate patriot, he speaks to Kaushik

Sankar Das of The Daily Star.

DS:

How do you feel about the country as a freedom

fighter after 33 years of independence?

DS:

How do you feel about the country as a freedom

fighter after 33 years of independence?

MH:

I feel I have contributed my fare share

in the making of this nation. At that time

victory was not a destination, it's just

a beginning of a journey. But now after

so many years of the freedom struggle, I

have to say that the state of affairs in

Bangladesh, in my opinion, is in a stage

of decay and it's unfortunate that I have

no option but to watch from the sidelines.

DS:

May be you could have done something for

the country from the position you held over

the years?

MH:

Well, as a government servant I couldn't

do much. But I have done whatever I could

with a clear conscience. If there were any

errors in my judgement, it occurred not

because of my dishonesty or self interest.

Because to me, my country always came first.

I have been loyal to it all along, wherever

I served, whether in the armed forces or

as an ambassador for sixteen years and various

positions. At the end of the day my conscience

is clear.

But

after more than three decades of independence,

we have lawlessness, brutalities and developed

a feeling of simply grabbing whatever we

want. We are loosing all the habits of a

civilised living. People of Bangladesh have

been accustomed to lawless conditions for

so long that they are no longer law abiding.

Only gun is feared today. Terrorism, corruption,

injustice, poverty, inequality and uncertainty

has become a way of life for people in Bangladesh.

DS:

So do you the regret fighting for your country's

independence?

MH:

I don't regret it at all. as such. Till

today it was the best phase of my entire

life. I spent nine months in the battle

field fighting for my country that brought

me more prode, satisfaction and enjoyment

than any other of my duties. I have had

a lot of important assignments in my career,

but nothing could ever match the days of

fighting for my country. And if the need

arises, I would fight again.

But

the question is whether those in the leadership

have failed the people of Bangladesh. I

agree that like others I am also responsible

to a certain extent, but others were more

responsible because they decided the destiny

of the country.

DS:

But you were in the armed forces when martial

law took over the power and stayed there

for a long time. May be you could have done

something in that undemocratic, uncertain

situation?

MH:

What could I have done? May be carry out

another coup? That was something I did not

believe in. I never believed in conspiracy

or unethical activities. I believed in people's

participation in forming governance. And

they toppled the martial law government

with a popular movement in 1990. But remember

all these situations arose because of lack

of responsible political leadership. When

a country is well managed and the constitution

is truly respected, no captain, colonel,

major or general can come out of the barracks

and stage a coup. The vaccination against

military coup is good governance.

DS:

During your tenure as an ambassador, the

country was under military rule. How did

you cope with the situation?

MH:

I admit that it was a sorry state and I

had to answer a lot of questions. I represented

my country under two democratic governments

too. But honestly there was not much difference.

The country's image in the world, I would

say, was nothing much to talk about. We

have had three democratic governments since

the nineties, but you tell me what's the

state of the country now.

DS:

Why are we still trying to find true stories

of the liberation was from those who were

actively involved in it?

MH:

We are living in a country where our past

has become unpredictable more than the future.

History is being written in loose leafs;

with the change of each government, new

pages are being added and old ones are being

taken out. To tell you honestly, I am really

amazed at our immaturity, the national culture

of immaturity and unpredictability. After

33 years of independence, we are still making

list of freedom fighters, the number in

that list is getting bigger and bigger by

the years.

During

the war, I had problems recruiting new members

for my regular battalion, and now you hear

thousands and thousands have certificates.

Yes there were organisers and passive supporters,

I do not want to undermine their contributions,

but who were fighting in the fields, who

took up arms, who were willing to sacrifice

their lives?

Most

of our recruits were farmers and young boys.

You would be amazed to know that I had as

young as 14 year old boys in the battalion

fighting. I do not see many of them cueing

up for certificates? And who are issuing

these certificates? They might have legal

authority, but what moral authority do they

have?

Let

me tell you a story. Once I received an

official letter that said if I wanted to

get certificate of a being a freedom fighter,

I had to be recommended by my Thana Commander.

I laughed because I myself was commander

of a battalion. It was ridiculous!

DS:

Is that the reason you do not mention the

gallantry award after your name given to

you for your contribution in the war?

MH:

I think the gallantry awards were given

indiscriminately and without much investigation.

Gallantry means fighting in the battlefields.

So I thought it was appropriate for me to

accept it, since I fought in the battle.

But I think the award was also given to

people who never fired a shot in anger.

I

am, not angry about it, but to me it doesn't

mean anything any more. That's why I do

not use it after my name. The mere fact

I arrived in Dhaka on December 16 in a uniform

with my 800 troops should be enough. I got

my recognition from the people who fought

along with me for my own satisfaction.

DS:

How do you feel about the politics surrounding

the liberation war?

MH:

Every year when March and December comes,

we say that Muktijudhho is our pride, the

rest of the ten months it remains an ornament.

We Bangalees love myths. There are lots

of myths surrounding the liberation war.

Children are being taught those myths, which

may not be true, but fascinating stories.

It's unfortunate that we are still quarreling

over this. As a nation we remain immature.

We

must know our past. We can only build our

future based on the values and spirit of

the past. But definitely not based on falsehood

and lies. Truth must be known to people.

The efforts should be to separate the facts

from fiction.

Every

political party used freedom fight and the

fighters for political mileage instead of

genuinely respect the sacrifice and courage

of the fighters. They all tried to monopolise

the war of independence. It should not have

been. Many people like me fought for certain

values. We fought because we thought people

wanted freedom from Pakistan. Life is full

of risks. I was not afraid of death, but

I was afraid of my life on my knees under

the Pakistanis. I revolted though I had

oath of allegiance to Pakistan and its constitution.

But I was more loyal to my sense of honour

and dignity.

We

accepted certain political leadership because

they were elected representatives. But whether

the political leaders have been able to

uphold that pride, honour and dignity is

a million dollar question.

DS:

Do you see any lights of hope at the end

of the tunnel?

MHC: I don't really know. I would say that

the disease has spread, like cancer, to

all parts of our society. We are so foolish

that we behave like beggars. Give a beggar

a horse, he will ride it till death. Let's

not do that.

I

have stopped believing what I hear from

our leaders. I only believe what I see.

Celebrating independence has become a ritual.

But I would ask our leaders who celebrate

the day to search their souls. They should

ask themselves what have they done to celebrate

the victory day, what have they done for

the country. They should ask their conscience.

Streets

of Dhaka on 16 December

Nilufar

Begum

When

we heard about the offer to surrender of

the Pak Army from General Manekshaw of the

combined forces we were contemplating over

the reaction of General Niazi to it. Our

utmost concern was whether the Pakistani

General would accept the offer or not. We

were very much terrified over the consequence

of rejecting the offer by Niazi.

When

we heard about the offer to surrender of

the Pak Army from General Manekshaw of the

combined forces we were contemplating over

the reaction of General Niazi to it. Our

utmost concern was whether the Pakistani

General would accept the offer or not. We

were very much terrified over the consequence

of rejecting the offer by Niazi.

As

the day passed, our anxiety and restlessness

increased. With the passage of every minute

we became desperate to know about the latest

position. The transistor and particularly

the news broadcast of the foreign Radio

stations were the only sources of information

for us. It however did not help us much.

Three

migs, obviously Indian ones flew in the

morning over the sky of Dhaka. We still

could not conclude about the fate of the

surrender offer though the deadline for

accepting it was already over. As there

was no other visible sign of the surrender,

anxiety turned into great apprehension.

We started thinking perhaps the last battle

is going to be fought very soon.

It

was noon. The elders were pale and terrified.

It had its repercussion on the younger lot

too. This could not, however, stop their

war-play. Occasionally they asked -- why

the flocks of Migs don't play in the sky

to-day? Why there is no sound of firing?

Naturally there were very few responses

to their queries.

It

was about 2.30 pm, just after having lunch,

all on a sudden a very known horn and engine

sound surprised us. It was my elder brother

who just parked his car outside the gate

of our house and knocked at the door. He

was smiling, beaming with joy -- and triumphantly

broke the news of victory to us. 'Don't

you know Niazi has declared to surrender?

Very soon he will formally surrendezr to

Lt. Gen. Aurora at the Race Course.'

We

hurriedly got into my younger brother's

car and started for the Race Course.

On

our way we saw a group of men assembled

in the Nimtali Rail crossing and seemed

to be whispering with each other. They were

at first surprised to see us in a car out

to move around in the city. Then suddenly

one or two of them greeted us with the slogan,

'Joy Bangla'. Instantaneously we all reciprocated

quite vigorously, for a moment we were carried

away by a sentiment of oneness and victory.

Crossing

the Railway Hospital we proceeded to the

direction of the then DPI office. There

was hardly anyone on the street. Unexpectedly

we saw a small procession of ten to fifteen

men at best in the corner of the old High

Court building. A few kids were also among

them. They were carrying triumphantly the

new flag of the newly born country. We waved

at them and they replied in chorus with

thundering slogan 'Joy Bangla'.

When

we reached near the Engineers' Institute,

we were stopped suddenly by the soldiers

in a truck. They forbade us to proceed further.

We could not exactly recognise them to which

side they belonged. We had to turn back.

Keeping the Ramna Garden to our left we

then started for Tenement Road where Mr.

Mahammad Ali, my younger brother's friend

and a co-fighter in the liberation struggle

used to reside. He was completely taken

aback to see us. Until then he was unaware

of the surrender of the Pakistani Army and

the consequent liberation of our country.

On getting the information from us he was

choked with emotion and delighted in joy.

From

there we started again for the Race Course

by a different road. After proceeding a

while a pickup with a few non-Bengaless

suddenly overtook us in a menacing way.

Immediately after that a jeep arrived on

the scene. It came just behind us. It seemed

the jeep had been following the earlier

pick-up. Suddenly they started exchanging

fire. We were caught between them. Fortunately

we managed to save ourselves and got a way-out.

Quickly we entered into an empty house to

save ourselves.

When

the exchange of fire stopped we hurriedly

came out of our temporary hide-out and tried

to return to safety in Tenement Road. We

were told that it was not yet safe to move

in the street as many Pakistani soldiers

were unaware of the surrender till then

and as such could fire at anybody they saw

in their way. At this stage we became really

nervous and desperately wished to reach

home safely.

On

our way-back we saw in few places non-Bengalees

lying in position with their machine guns

in ditches, bushes and behind walls and

bearded Mukhti Bahinis in batches to wipe

out the remnants of the Pakistani resistance.

Changing

our route we came in front of the Gulistan

Cinema Hall. Here again we were intercepted

by two Bengali patriots. Greeting us 'Joy

Bangla' they asked us not to go towards

the then Fulbaria Station. Pakistani soldiers

were still on guard there. Expressing our

gratitude to them we changed our direction

and came in front of the then DPI Office

through the Secretariat road. Suddenly our

attention was drawn to dead body lying on

the other side of the road just in front

of the former BNR office. We were simply

thunder-struck at the sight. Oh God! It's

that young man who was carrying the flag

of new nation; who was at the head of the

small procession, we saw an hour ago; who

shouted 'Joy Bangla', at us and whom we

saluted in respect. But the murderers have

not been able to snatch away the flag form

his hand. He has lost his life but he has

not given up the honour of the nation.

We

then turned to the FH Hall and thought to

be completely safe but all on a sudden quite

unexpectedly we were in the midst of a large

number of soldiers who were passing through

the road.

They

were in two rows and we found ourselves

between their rows. At first we considered

them as Indian soldiers and as such we greeted

them by waving our hands. Soon we realised

our mistake and shuddered in fear. They

were Pakistanis, damn-tired, dispirited

and demoralised -- marching towards the

Race Course for their formal surrender.

In

such a situation our car came to almost

a dead stop. We took about ten minutes to

cover a distance of two seconds -- from

Curzan Hall corner to the Railway Hospital

(present Karmachari Hospital) turning. When

we were passing through the rows of Pakistani

soldiers we were apprehending death at any

moment. We were perhaps counting moment

of our final end.

When

we reached Railway Hospital turning we saw

two fresh dead-bodies lumped together on

the street. We thought they had been killed

by the same Pakistani soldiers through whom

we passed a few moment's ago. Seeing these

dead-bodies we pondered why they had not

killed us? Until today I have not got the

answer to this query.