Following

the path

of freedom

Fayza

Haq

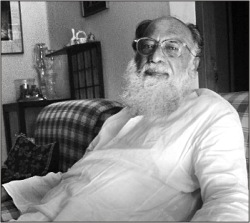

People

were working in TV on the subject of liberation

before the Liberation War,' says Mustafa

Manwar, recounting his experiences of the

liberation movement. 'There was the Jagorini

Gan. We had no means of special effects

and used a mirror or a camera to produce

the effect of 1,000 people. This went hand

in hand with songs like Songram, songram

cholbey. I was then the programme manager.

We had worked with Shukanto's poetry, Deshlai

and Runner, a small boy being included in

every procession in the city. We used to

be ready with the child in a car, and every

time we heard that there was a procession,

we went to it, with the boy. This portrayed

how this child was calling the people to

join the forces of liberation, the child

being the symbol of freedom. We could not

directly spell out that this was the call

for freedom. There was a sound of gunfire

but the child would pick himself up and

continue with his struggle. This proved

to be effective.

People

were working in TV on the subject of liberation

before the Liberation War,' says Mustafa

Manwar, recounting his experiences of the

liberation movement. 'There was the Jagorini

Gan. We had no means of special effects

and used a mirror or a camera to produce

the effect of 1,000 people. This went hand

in hand with songs like Songram, songram

cholbey. I was then the programme manager.

We had worked with Shukanto's poetry, Deshlai

and Runner, a small boy being included in

every procession in the city. We used to

be ready with the child in a car, and every

time we heard that there was a procession,

we went to it, with the boy. This portrayed

how this child was calling the people to

join the forces of liberation, the child

being the symbol of freedom. We could not

directly spell out that this was the call

for freedom. There was a sound of gunfire

but the child would pick himself up and

continue with his struggle. This proved

to be effective.

'There was then the recitation

of poems of rebellion taken from Tagore

and Nazrul, like Nai nai bhoey , Hobey hobey

joey, Sikander Abu Jaffer's Jonotar shangram

cholbey, and Ektara tui desher kotha bol.

These used to be illustrated and I did the

drawing and painting for this.'

On 23rd March, they realised

that there was no flying of the national

flag in the city of Dhaka, and they were

compelled to fly it on the TV. They had

a plan. Normally the TV then went on till

10pm. They decided to have patriotic songs

till the end. There were about 50 Pak soldiers

camped in the TV station and the major in

charge asked at 11pm why the programmes

were not finishing. Finally, there was only

a handful of TV workers, and Masuma Khatun

said that she would make the final announcement.

At two minutes past midnight, she announced

that it was the 24th March and that the

programmes had ended. Thus the TV authorities

had defied the regulation of flying the

flag on the national day. After that we

all went into hiding. This was followed

by the crackdown on the 25th.

'At Agartala, we did some

recordings of songs and went onward to Kolkata.

We formed a cultural team, that I headed,

and went to different parts of India. Waheedul

Haque looked after the musical section,'

Mustafa Manwar said. The artists who had

gathered there from Bangladesh presented

an exhibition, under the banner of the Liberation

War. Shug Dev did a documentary of the time

and included the works of the different

artists. Mustafa Manwar's own painting was

that of a mother holding a wounded and dying

freedom fighter on her lap. She was seen

sitting on a 'char'. Dev Dulal Bandy-opaddhaya

praised this effort. They held a large function

on TV in Delhi.

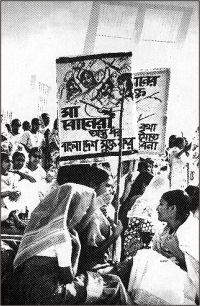

Visiting the camp of the

refugees from Bangladesh, Mustafa Manwar

found all the inmates often grim and depressed.

To change their mood he decided to introduce

puppets. Among the puppets were the characters

of Yahya Khan and an ordinary farmer. This

brought fun and frolic. 'After a long time

we laughed,' people said, and this gave

Mustafa Manwar a lot of satisfaction. A

visiting American documentary maker made

a film of these puppets. Later, Tarik Masud

added many shots to those taken by a foreign

film maker and called it Muktir Gaan. Artists

often made posters under the guidance of

Quamrul Hassan and took out processions

with them. Thus, cultural teams worked in

Kolkata and different parts of India in

praise of the liberation movement. Someone

from UK collected the paintings of Bangladeshi

artists and printed them overseas.

Mustafa Manwar came back

on December 18, 1971, being among the first

group of civilians to return to Bangladesh

from India by plane, and with the return

of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, they presented

TV in a different way. Now the Bangl-adeshi

culture was no longer to be muffled. Meanwhile,

at this time, Shawkat Osman wrote a long

article on the Liberation War in the newspaper

Desh, and Mustafa Manwar did all its illustrations

in six issues. Renowned filmaker Satyajit

Ray, on seeing these drawings, was very

impressed.

Passion

for independence

Novera

Deepita

The

station of Shwadhin Bangla Betar Kendra

(SBBK), situated at Ballygunge Road of Kolkata

came to be recognised soon as Mujibnagar.

Buoyed by the spirit of the Liberation War,

Rothin joined the radio and his voice was

his weapon for the war.

The

station of Shwadhin Bangla Betar Kendra

(SBBK), situated at Ballygunge Road of Kolkata

came to be recognised soon as Mujibnagar.

Buoyed by the spirit of the Liberation War,

Rothin joined the radio and his voice was

his weapon for the war.

SBBK started its journey

in May right after the formation of the

Mujibnagar Government in April 17, 1971.'My

songs O Biral rui machher matha khaiona,

Joy Bangla boila re, Amar neta tomar neta

were already being aired even before I joined

SBBK,' says a nostalgic Rothin.

In April eminent filmmaker

Subhash Dutta first told Rothin about SBBK.

However, it was not until June that Rothin

could join the radio. 'Although I passionately

wanted to join the Liberation War, I never

wanted to leave the country,' says Rothin.

However, the situation soon grew hostile,

'especially for the Bangalee minority.'

So, one night in mid-May,

Rothin and his family set out for the Indian

border. Rothin still remembers the horror

of that journey. 'About 500 rickshaws were

moving very slowly along the Dhaka-Chittagong

highway. What was most amazing was that

there was dead silence every where-- even

the children forgot to cry!

Rothin left his family safely

at Jalpaiguri and came to Kolkata by train

to locate the office of SBBK. 'I didn't

need a ticket on the train. The Indian trains

at that time were free for anyone who would

say "Joy Bangla",' fondly reminisces

Rothin.

However, Rothin's entry

to the SBBK office was not easy. 'I only

knew that it was in Ballygunge Road but

didn't know the exact location. When, I

finally found the Bangladeshi High Commission

at Balu Hakkak Lane,' Rothin says, 'the

guards would not let me in.' 'I was in deep

trouble since I had burnt all my papers

and documents to avoid identification. Somehow,

I was lucky enough to find my certificate

of being an enlisted artiste,' recalls Rothin.

The guard finally showed

Rothin the nearby office of Joy Bangla,

a newspaper brought out by Bangalees. Here

I met Shah Ali Sarkar, who is one of the

founding members of the SBBK He was overwhelmed

when he learnt my identity. The next morning

I met my friends Abdul Jabbar and Apel Mahmud.

There were other people from Bangladesh

Betar including Ashfaqur Rahman Khan, Motahar

TH Shikdar, Shahidul Islam and Kamal Lohani.

I was greeted warmly by all of them,' reminisces

Rothin.

On the very first night

of Rothin's arrival at SBBK, Apel Mahmud

said that he had tuned a song for him. Rothin's

first song with SBBK was Tir hara ei dheuer

shagar, written by Gobinda Haldar. 'In the

evening we recorded the song and it was

aired the next day. It became very popular

instantly,' recalls Rothin.

'The recording machine was

a very ordinary compared to the facilities

of today. Our only duty was to record the

programmes and keep the tapes in a safe

place. We were not told from where the songs

were transmitted,' says Rothin.

'After a few days, eminent

musicians Samar Das, Ajit Roy and Shujeo

Shyam came to SBBK. Their arrival added

a new dimension to the productions. For,

these artistes composed innumerable inspirational

songs with passion and patriotism,' comments

Rothin.

Rothin says, 'Songs like

Purba digantey shurjo uthechhe, Nongor tolo

tolo, Tara e desher shabuj dhaner, Swadhin

swadhin dikey dikey had been composed then.

Joy Bangla Banglar joy was the signature

tune of the station. It was actually a song

composed for a film. Gazi Mazharul Anwar

was the lyricist. Composers like Shahidul

Islam and TH Shikdar did many inspirational

songs. I have recorded more than 50 songs

during the Liberation War. Among my other

popular songs are Chashader muteder majurer,

O bhai khati shonar cheye, O bogilarey,

Poraner bandhu re, Amar desher shonar dhan,

O bhai mor bangalee re.'

The artistes of SBBK used

to go to the camps of freedom fighters in

the Muktanchal and in the refugee camps

to inspire them. Rothin vividly recalls

many emotional incidents of that time. A

team had come to recruit freedom fighters.

A boy who sought membership in the team

was adamant about going, against his mother's

will. The boy got into the truck while the

mother desperately ran after it and pleaded

with her son to have his last meal from

her. Can you tell me how I can forget that

moment?' says an overcome Rothindra Nath

Roy.

'Stop

Genocide'

Depicting

the actual

massacre

Afsar

Ahmed

An

old lady is journeying towards an unknown

destination leaving everything behind--her

motherland, her home, her blood relations

and her dreams. The toils and travails,

the agonies depicted in her face are enough

to touch anyone's heart. This scene from

the documentary Stop Genocide is so moving

that anyone can feel the horror of the brutality

and genocide going on in the then East Pakistan.

Stop Genocide was the perfect depiction

of that time,' says a nostalgic MA Khayer,

who was the in-charge of the Film Division

of the Mujibnagar Government's Information

Ministry in 1971.

An

old lady is journeying towards an unknown

destination leaving everything behind--her

motherland, her home, her blood relations

and her dreams. The toils and travails,

the agonies depicted in her face are enough

to touch anyone's heart. This scene from

the documentary Stop Genocide is so moving

that anyone can feel the horror of the brutality

and genocide going on in the then East Pakistan.

Stop Genocide was the perfect depiction

of that time,' says a nostalgic MA Khayer,

who was the in-charge of the Film Division

of the Mujibnagar Government's Information

Ministry in 1971.

'The film was completely

Zahir Raihan's concept. He firmly believed

that a film projecting the true picture

of brutal human rights violation by the

then Pakistani government could create world

opinion against those acts more effectively

than meetings and processions. It was during

April-May 1971 when he came up with the

concept of making a film on the genocide,

but the Motion Picture Association of Bengal

didn't take it seriously at first. Finally,

however, Zahir Raihan convinced them and

the rest is history.'

Directed by Zahir Raihan

with the assistance of Alamgir Kabir, Stop

Genocide faced a lot of obstacles especially

regarding its finance, says Khayer. 'The

Motion Picture Association of Bengal helped

a lot for financing the film. Dr AR Mallick,

the Chairman of the Liberation Council of

Intelligentsia, also provided the financial

help for the film,' he informs.

Abul Khayer also came forward

to promote the film on behalf of the Mujibnagar

Government. 'But the path wasn't that easy.

The inside story was different. The then

Mujibnagar Government wished to produce

film on the Liberation War and its leadership

rather than the genocide. The principal

reason of their objection was a missing

link in the film: the absence of our great

leader Bangabandhu,' says Khayer. 'But,

Zahir Raihan wanted to earn recognition

of our war of independence. He firmly believed

that the whole war was by the name of Bangabandhu

and, at the same time he also believed that

the whole world knew it. Even, all the slogans

contained his name and the freedom fighters

used to take oath by his name. Raihan felt

that it wasn't necessary to highlight Bangabandhu

again and again and intentionally left out

his name from his film.

'But Zahir Raihan had a

completely neutral angle in this regard:

he was more willing to project the real

picture of the genocide than the political

affiliations of the war for creating more

effective opinion,' says Khayer. The brutality

of the genocide and the apathy and the struggle

of the migrated general people were the

main theme projected in this subtle documentary.

The language was simple and appealing. And

that's why, Stop Genocide acclaimed the

emblem of the true picture of that time,

as Khayer perceives.

'On its first screening

at a secret place in India, the cabinet

of Mujibnagar Government including Acting

President Syed Nazrul Islam, Prime Minister

Tajuddin Ahmed, AHM Kamruzzaman and the

politicians present there became totally

emotional. The film also helped us gain

the Indian support in the Liberation War,'

recalls Khayer.

'It was the middle of the

war and we were in Kolkata. The cabinet

of the Mujibnagar Government decided to

make another film on the Liberation War

by Zahir Raihan. Tajuddin Ahmed himself

asked me to tell Raihan about the project.

I contacted Raihan and he didn't refuse.

He made four films out of the budget sanctioned

for him! The films were Birth of a Nation,

Children of Bangladesh, Surrender and the

other one I can't recall now. The films

were very well-made but we are so unfortunate

that we couldn't be able to preserve these

films.

The films were sent from

India and Khayer is sure that the films

reached the soil of Bangladesh. But he cannot

tell how they have lost forever. 'We can't

preserve our heritage--our past achievements,

those glorious events and people behind

them,' regrets MA Khayer.