Fearless

female fighters

Manisha

Gangopadhyay

When

Shirin Banu joined the Liberation War of

1971, she disguised herself as a man. That

was the only way she could take part and

being woman did not stop her. Alamtaj Begum

Chhobi was only 16 and though her mother

was against her going to war and her community

outcasted her, she still fought her way

through those terrible days of 1971. Unlike

Chobi, Farquan Begum's parents, freedom

fighters of another war, trained her to

fight. In her own word, "Fighting for

freedom is in my blood."

Each

freedom fighter joined the war efforts through

political affiliations which acted as launch

pads and support groups in the cause for

freedom and independence. But they did not

discontinue their struggle for humanity

after the war was over. They continued to

work for women's rights, environmental causes,

peace.

It

is unfortunate that those who fought the

war were pretty much forgotten, because

they have incredible stories to tell. It's

strange how those who did the most for Bangladesh

received the least in return.

Alamtaj

Begum Chhobi

Alamtaj

Begum Chhobi

In 1971, I was just 16 year old and an active

part of the leftist party of Barisal. I

was too young to know what it really meant

to be a political activist. I did not know

what would become of me, what people would

say.

I

first came in contact with the leftist movement

when I was in class 9. I started absorbing

ideas through my brothers, Humayan Kabir

and Firoz Kabir, who were very active in

the movement. They would have their fellow

party friends over the house quite often

and I would overhear what they were talking

about as I served them tea. I read the leaflets

they left lying around the house. Pretty

soon I was helping them write the leaflets

and paint walls with slogans using crushed

coal for ink.

In

those days women had to wear a 'ghomta'

(a veil over their head). Things like romance

and talking to boys were not done, at least

not openly. Women did not have exposure

to a lot of things. Nevertheless, when the

time came to stand side-by-side with the

men to defend the country, women stepped

up to the cause.

No

woman was forced to go or called to go.

Everyone went on their own. What was the

point of staying home? Either way we would

be attacked at the hands of the Pakistani

Army or by rajakars (Bengali collaborators).

My

mother cried a lot when I left. She still

cries for my brothers who died in the war.

When

I joined, I met many courageous women Monika,

Bithika Ray, Reba, Rekha, Nur Jahan. Some

had been tortured, some had lost their houses

to arson, some came with their husbands.

My

first weapon was the 3-knot-3 rifle. We

didn't have a whole lot of arms. Later I

carried a light machine gun (LMG), the pistol

and hand grenades. At first I was scared

about joining the war. But then my courage

built up and it has stayed with me. To this

day, I have no fear of dying.

When

the Liberation War began, Bengalis formed

a togetherness for one cause that had ever

existed before or will ever exist again.

There was no difference between male and

female. We often slept side by side across

the floor, but at no point were we ever

disrespected.

I

wore a sari when I joined, then I started

wearing a lungi. When that became too inconvenient

and finally I moved on to wearing shirts

with pants.

It

was the practical thing to do. We had to

go through rice paddy and khals (small lakes),

wading knee-deep in water. Sometimes the

water even came up to our shoulders.

We

had to stay in the same clothes often for

4 or 5 days at a time without bathing or

eating.

During

the war I killed members of the Pakistani

Army and rajakars. I used my guns and I

used my bayonet. I gained a lot strength

of mind during that time. That strength

of mind is helped me through the bad times.

The

first man I killed was a rajakar. I thought

it was justified because he has betrayed

and wronged people. The rajakars, who were

Bengalis, would guide the Pakistani Army

to houses that had young women or active

freedom fighters. The Army tortured, raped

and killed these people to set an example

and send a message to the terrorised Bengali

people on where they stood.

When

victory was declared in December of 1971

it was the most joyous moment.

My

return to home was a different story. People

did not look highly on women who joined

the war. And though not a single Pakistani

Army officer had laid a hand on me during

the war, rumours had gone around about the

possibility that I was manhandled or worse.

Two months after independence, my husband

was lured out of our house by government

officials, taken to Jhalokati and killed.

I was three months pregnant.

After

his death, I went to a relative's house

in Dhaka because I knew I would not be accepted

back home. She sent me back to my father's

house. The community did not receive me

well. My parents took me in, but I got cold

treatment. I kept going back and forth between

my in-laws house and my parent's house.

I

knew I had to stand on my own. I took up

odd jobs paying a monthly salary of taka

40. I sewed, I tutored until I was financially

solvent. I used to cry a lot. I used to

beat my daughter. I took my anger out on

her. I have nothing to hide. Have I said

anything that should bring me shame? This

is just the bare truth.

What

I faced after I returned from the war, it

cannot be expressed in words. And it did

not stop with family and community. Politics

that was once a higher cause, became debased.

Since independence, I have not continued

politics. I have been earning a living and

raising my family. I have learned a lot

from life experience. My mission is to pass

this knowledge to my daughters. The pain

of hunger is a strong pain. The real war

is not fighitng in the battle fields. It

is what comes after the War.

I

have led a very different life. I am happy

about that. It has given me the opportunity

to have many valuable life experiences.

If

I could tell anything to today's young woman

I would tell them to educate themselves,

they have many opportunities we didn't.

Learn to stand on your own.

Many

people have asked me to join politics. But

I didn't. I regretted making that decision

at the time, but now I know I made the right

decision. I have never asked anyone for

anything. That may be why I did not receive

recognition.

The

interview I gave for BBC and German radio,

my words in The Daily Star, these are my

certificates. I do not need an inauthentic

"official" certificate from the

government. I may not be well-educated,

but I know right from wrong.

Shirin

Banu

Shirin

Banu

I grew up in a political environment. My

mother and father were both part of the

Communist Party. In fact my mother was the

'Gono' Party's central member. My maternal

uncles were also very political. My involvement

was a long-term process - it didn't just

start with the War. At the time the war

started I was studying Bangla Honours at

Edward College.

Women

fought in different ways away from the forefront

in the Liberation War. They somehow, almost

miraculously tore down trees and laying

them down on streets, barricading the Pakistani

soldiers from moving forward. To Bengali

freedom fighters they provided rice, shelter

and information. Every house was a camp

against the Pakistani Army.

Socially,

women could not just join the war by showing

up in a sari. I went in men's clothespants

and shirts. I was 21 year old, lean and

thin. Nobody could identify me as a woman.

Only a couple of my close associates knew.

Pakshi

Bridge in Pabna is where I saw my first

armed conflict. I was in the forefront at

the first phase of the war. There were 28

of us in my military camp. Almost all of

them died. Sometimes people who were right

next to me were killed.

What

I saw as we moved forward was the remains

of massacre after massacre. Lots of corpses

on the streets. The group often had to split

up, we were often separated for long periods

of time from those we knew through the struggle.

When we advanced from Pabna to Pakshi Bridge

in Kushtia, I found myself among a group

of strangers. When I did come across familiar

people and we inquired about people who

were missing I would get answers like "He

died in the juddho."

When

I first saw a Pakistani soldier, I was disgusted.

Our rights, our votes, we should have had

our Prime Minister, but they denied these

things to us and instead turned on us.

The

freedom struggle was the work of a lot of

anger about that, which is what gave us

the inspiration to fight.

There

were some difficulties as a woman. In order

to hide my identity, I would not bathe for

days. Sometimes, I would go 10-15 days with

bathing. A cousin who knew my identity,

would explain to the others in the pond

that I didn't know how to swim. When I had

to go to the toilet, I had to wait until

night.

The

Pabna District Comm-issioner, Nurul Kader

Khan knew there was a woman among the group,

but he couldn't identify me even when I

was standing right in front of our group

as he addressed us. Once a foreign journalist

who found out their was a woman in our regimen,

asked to see me. Mr Khan asked our group

where I was. He was shocked when someone

responded pointing to me, "She's here."

The journalist took a picture of me with

a gun, which brought me a lot of recognition.

The Statement of India, wrote a piece about

me titled, "A Shy Girl with a Gun."

But I actually fought only for a short time

with arms. There were so many others, Taraman

Bibi, Runa Das, Bithika Biswas who fought

with me. But they didn't get published at

the time.

I

was in Pabna till April. I carried a 3-knot

3-Rifle, a 2-2 bolt these were weapons our

Pabna DC collected from the police to distribute

to people. We didn't have many arms. We

used what we had. I started off using a

large fish 'boti' (knife to cut fish) for

a long time. When we ran out of ammunition

we had to retreat further and further. We

eventually went to India for support and

to request for more weaponry. In India,

they didn't give weapons to us at first.

There

was a training camp for women. Sajedur Chowdhury

was in charge of the women's training camp

in India. I was in the first batch, which

had 234 women. We organised ourselves and

motivated the people of India to support

the Bangladeshi cause. The Communist Parties

of the two countries had a strong link.

I

provided nursing and military training to

some of the women in the camp. Though I

thought I would eventually return to Bangladesh

to fight in the war, I did not end up returning

for the rest of the year. My first day back

in Bangladesh was first of the new year,

1972.

When

the war was over, we thought all of our

dreams would come true. All of our dreams

did not materialise. Our secular constitution

was replaced with an Islamic constitution,

we did not get freedom of religion, freedom

from hunger, freedom from discrimination.

There

is a long history and politics behind the

war. A lot of misinformation has been produced

since 1971 and now it is creeping into our

children's history books. That is why it

so important for me and others who were

part of history to tell our stories.

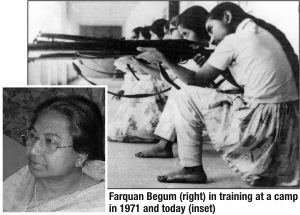

Farquan

Begum

Farquan

Begum

The Liberation War of 1971 didn't just begin

overnight. It took long years of mobilising

people towards the cause of gaining an independent

nation. It took time to motivate people,

educate people on their rights, and prepare

people for this kind of movement. My family

and I had been involved in this process

leading up to the war.

Fighting

for independence was in my blood. My mother

was a "Bhasha Shohinik" (activist

in Language Movement of 52). Before that,

my parents and maternal uncles were active

in the struggle for independence of India

from the British. The Brits called them

"terrorists".

I

had been involved with Chatra League for

years. The West Pakistan governance created

a disparity between the two Pakistans, they

cheated us. We realised we had to stand

on our own, we had to survive, we had to

protect ourselves.

Bengalis

are generally a peace-loving people. But

when the Pakistani's unleashed such unbridled,

inhumane atrocities, we as a people became

furious.

When

the war started, I helped establish camps

for those who lost their homes. Among the

displaced in the camps, we selected the

young, strong ones to fight in the war.

We collected arms and provided arms training.

We

also collected funds for food, shelter,

medicine and establishing nursing centers

for the wounded. I was the leader of the

Women's Guerilla Squad in Agartala. I trained

women to fight and use arms. We used our

friends and relatives who were on duty in

the Pakistani Army to help us free the captured.

Because

of all my activities, I always carried a

Chinese pistol. When I was with the others,

fighting on the streets, I carried grenades.

During

this terrible time, I saw villages set on

fire, burning in the wake of the Pakistan's

infiltration. The corpses we saw along our

path saddened me and fuelled the fires to

fight against injustice.

Sometimes

we didn't eat for days, we walked miles,

sometimes eating fruits on our way.

I

did not face too much trouble joining the

cause of war as a women. Actually, I was

trained from childhood to do this. Besides,

I went to a coed school and came from a

broadminded family.

We

all went through lots of trouble, but we

did it for love of our nation. In the name

of "Desh Prem" people can do anything.

After

Muktijuddho, I did not associate with any

political party because the country was

free. The political party was just a vehicle

to get there. Instead, I put my energies

into social work, humanist activities, working

for the poor. I write and I have actively

called on the government to recognize freedom

fighters.

When

we were fighting, we had a dream that all

our people would be able to eat and enjoy

fundamental rights. However, big powers

have a role to play, they make the rules,

preventing us from realising those dreams.

We,

the smaller countries must demand that the

big powers play fairly.

Right

now, I am 'hanging' in between jobs. I was

a Deputy Director and Senior Assistant at

different levels of a ministry. But because

of my associations before the war, sometimes

we get shafted by different governments.

Those who fought for the cause of war all

were involved in political parties, it was

for a greater cause. But now we are being

punished for that.