Inside

|

|

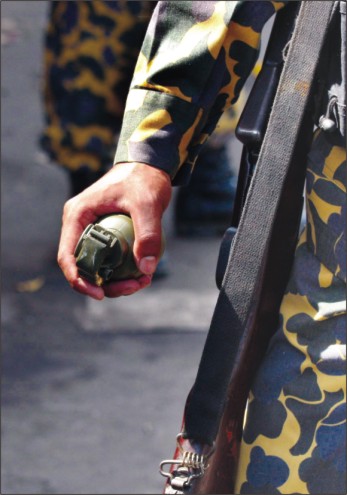

Afsan Chowdhury THE Pilkhana incident has restored mutiny and violent deaths to the centre of political discourse after many years. The role of institutions like the army and its auxiliaries like the BDR and the Ansars have returned in full force, making everyone anxious to understand what they mean in terms of law and order stability and the character of the state institutions that house such forces. The blood spilled at Pilkhana has shattered everyone's sense of a secure space where the armed branches of the state are concerned. Now, many will wonder if, given the existing framework in the armed branches of the state, somewhere, something is brewing or not at any time, which can suddenly explode as it did this February. Most view the matter largely as a law and order issue which can be fixed through punishment and discipline. Few analyses are exploring the internal crisis of a state arrangement where an entire institution of the armed variety can turn violently on another, in this case, the BDR on the army. To dismiss this as a law and order problem only would be troubling, especially in the case of Bangladesh where military intervention in matters of the state has a long history, as have been such revolts, especially in the army. Nor can conspiracy theories alone accommodate the explanations. The large-scale involvement of BDR personnel has also created blanket demonising of the jawans, which means all are presumed guilty until proven innocent. Till date around 150 have been charged and latest reports say at least nine have died from "suicide" and "heart attacks," presumably during questioning. While custodial deaths are a common practice in Bangladesh, it is disturbing now because if one falls into the trap of violating human rights of accused persons by an investigating agency, the price is always paid by the entire state. We do hear a lot of voices demanding death penalty and the harshest possible punishment for the mutineers. The numbers of mutineers also rise with every count. Prescribing death is always easy, but as our history shows, if, after all these years of formal management, violence can occur with such extreme force within the military and the para-military because some basic flaws were not repaired, some fundamental system of check and balance was not maintained by the armed branches with all their resources and personnel, there is cause for deeper worries. And it is not an internal crisis but it becomes a matter of public discourse. When so many are involved, it's not a conspiracy of rogue elements, but a structural problem. As the incident involves a gruesome array of killing of army officers, and human sentiments are still raw, any analysis of the situation has a chance of being perceived as either "pro-army" or "pro-BDR" in the present environment. For the moment, there is some feeling that the issue is very black and white, and that punishing the guilty will restore the situation. However, that is only partly true, as the problem is certainly much more complex in the context of our history since 1971. Threat to Post 1/11 It is this internal power equation between civilian politics and military support to that which has been threatened by this event, and it is this aspect of state management that needs to be analysed and organised and strengthened. The fear is not illusory. The way the government has been dealing with the investigation has drawn questions. Regular bulletins on the health and the direction of the civilian official investigation of the incident have already caused confusion. The minister-in-charge of the probes, Col (retd) Faruk Khan, has kept the public informed regularly of what is happening, so regularly that one wonders how such a sensitive investigation can be undertaken effectively, especially when his pronouncements often contradict that of other ministers. The extremist Islamic group JMB was linked, but that claim has now been withdrawn. Everything from the speed of the investigation and the subsequent trial and the jurisdiction of the trial including under martial law, has been publicly discussed. It looks like a government that is trying to convince everyone that it is serious about its wish to hold trials and thereby convince a part of the skeptical army that this isn't the old "anti-army" Awami League. Given that the massacre has happened under this government that has tried its best to handle it, the source of this anxiety appears obvious. One also hopes that here aren't too many crossed wires as we seem to be seeing. Sheikh Hasina is obviously not against the regular commentary of events because it expresses her sincerity to the public, but is this necessary when, barring hard-line BNP and Jamaat supporters, everyone is convinced that she does want a trial, does want a closure of the event, and move on. It is this anxiety that's causing stress all over. There appear to be four stages of the crisis. The first was the acute phase when the conflict occurred. The second phase is now on when investigations and interrogations are in progress. The third stage will be the trial stage when the evidence will be presented, the court will conduct the trials, and the judgments will be pronounced. The final stage will be the repercussions of all the sequences and the impact that will have on the state and its institutions. It is managing all four that is required, and AL seems to have done well in the first and is doing fairly well in the second with the help of the army. It's the third and the fourth which will decide which way the state will go in both the short and the long haul. Armed Rebellions in Bangladesh: Between 1972 and 1975, one sees an era of relative peace externally. Meanwhile ambitious senior officers to radical Leftists were trying to organise their own power spaces within. Several interviews conducted by the author on the 1975 events show that the military was restive due to a number of reasons, starting from wholesale takeover of captured Pakistani weapons by India, which the army thought the Bangladesh government should have protested. The raising of the Rakkhi Bahini by Sheikh Mujib as a politico-military force outside the army command was another cause of great resentment of the military brass and jawans. The resentment was also high amongst officers that the 1971 war had been appropriated entirely as a success of the Awami League leadership and it was not shared with the army or even the people. It was also being used for personal gains by some in cases. Finally, the freedom fighter officers resented the integration of repatriated officers from Pakistan into what was, in effect, a resistance army. The first cluster of military insurrections that began with the August 1975 coup broke the traditional pattern, as it was mounted by a clique of rebellious serving and retired officers, all war veterans, and not the national army. The main army was against it, but they were caught so off guard and were so confused that they were forced to go along. However, the Khaled Musharraf coup of November 3 was a better reflection of the mainstream officers' position, which was against the August group. But things became quite complicated on November 7 as Col (retd) Taher mobilised his subedars and introduced a new element in civil-military politics. By bringing in the officer privilege issue as a motivating factor, he was reflecting the Leftist ideology of the era that prevailed in most branches of politics. It was also the closest that any Marxist force of whatever description in Bangladesh reached the doors of state power. Zia's takeover and jailing of Taher the next day should therefore be called the fourth coup, and if Taher was in power on November 7, Zia came to power effectively on November 8, when the "sipahi-janata" insurrection was overtaken by the mainstream army's takeover. During Zia's rule more than twenty putsches were attempted, including the gory September 1977 coup when, taking advantage of the drama at the Dhaka airport, an attempt was made, which led to massive bloodshed at the airport, and much more deaths later of the losing party by hanging. It has never been properly explained why it happened or if all the hanged were guilty. Zia ultimately fell to the wrath of his disgruntled fellow officers on April 30, 1981, and Gen. Ershad on behalf of the army not only ended the Chittagong rebellion, but stamped his authority on the scene. So when he ultimately took over on March 25, 1982, he was really endorsing the obvious -- that the official military had taken over, not a faction. It was for the first time that a takeover without blood occurred unless one considers the April incident of Chittagong as an integral part of the plan (for which Ershad was being tried by the Khaleda government). The final coup attempt was in 1996 when the army chief Gen. Nasim was responsible for the crisis, but it was easily resolved, and after that there has been no further attempt till date. The coups were therefore always a result of several mixed causes. The first attempt was perhaps one that was almost entirely directed at ending the existing power group at the top in the shape of Sheikh Mujib, but it triggered a series of events that brought the internal crises of the army to the top too. Gen. Khaled Musharraf and Brig. Shafayet Jamil were trying to take out fellow officers gone rogue, to establish a chain of command, but it was swallowed by the national situation of that time. Taher could not have mobilised his subedars and soldiers if there had been no resentment against officers at a level where killing them was possible. Zia, too, took over because the internal image of Zia within the army was high and the soldiers saw him as more jawan-friendly than others. So these events were under the overall national arch, but the conditions lay within the army itself as well. The coups in Zia's era, including the one that took his life, were largely produced by internal discord of the military system. Other factors influenced, but essentially the institution had been seized by a huge crisis. It became stable, but only after considerable bloodshed and the takeover by the army as one institution not fighting with itself. To that extent, Ershad's takeover was a more institutional act of the military, which decided it was going to enjoy state power as it had already emerged as a guarantor of the state security, and the BNP government at that time was too weak to continue ruling or resisting advances of the army. The Para-Military Revolts: Para-Chowkidars and Para-Military The Ansar rebellion has almost faded from public memory because there was no significant bloodshed and it was put down by application of force led by the BDR. It occurred in two places, Sabujbagh/Khilgaon in old city and Shafipur, their main camp area. I covered the incident as a BBC correspondent and remember talking in the dark to the Ansars who were the most desperate and helpless sounding rebels/mutineers I have ever met. A few Ansars loitered outside the gate locked by them and gave me information about what was going on inside the premises. The Ansars didn't harm anyone, but the BDR did attack and kill a few, and the usual trials and punishments followed. Activist and social critic Farhad Mazhar took up their cause in his publication "Chinta" and said the following: There is no one in this cruel society to listen to the Ansars. In this intolerable environment, this uprising was inevitable. At the same time, we want to say with emphasis that the rebellion was also completely legal. Khaleda Zia's government put down the revolt after massive bloodshed. At the last count, even the most neutral news sources put the number of Ansar dead at thirty. In writing this report, Altaf Parvez has said: "Ansars are sons of farmers dressed in uniforms." Now we know that he was not the first to say this. The state, in its attempts to preserve law and order, gathers manpower from the oppressed subaltern class. The armed forces built with these very people are then used to further the rule of the oppressing and ruling classes over poor farmers, labourers, and the working class. Their revolts are suppressed. Killings are carried out. The BDR soldiers that shot and killed the Ansars are also the same "farmers in uniforms." And yet, the BDR soldier did not realise that he had just killed his own brother.1 Farhad Mazhar was jailed for his article and gained the ire of the military brass for writing and arguing with them on privileges and class issues within the ranks. Although his analysis was not comprehensive, the issue of class was clear. However, in a largely agro-society, almost everyone is a farmer's son. So going by that category, most people are farmer's children, including army jawans and army officers. What Farhad Mazhar said was that such revolts/uprisings/ mutinies were located in class conflicts and conflict with the state. This may not be a catch-all explanation, but is part of the package of reasons ranging from class to internal dissension. The idea is that the practice of jailing people for pointing out such issues indicates some of the problems rooted in the conflicts as well, including perceptions of privileges, class, and conflict, and mainstreaming them in public discourse. Which Brings us to the Present In view of the fact that the government may restrict access to information about the army under the Right to Information Act, there is an obligation even more now to discuss why the armed branches break out in violence and where some of the problems may lie, if only to point out that such restrictions may well perpetuate the problems that cause such mayhem in the first place. We shall hopefully know the details of the incident after the investigations are completed -- both civil and army -- but some facts are already clear. That there was resentment regarding several issues including poor pay, limited scope of promotion, army officers running the command, and the demand to be hired as UN peacekeepers. BDR personnel felt left out of the privileges package, which they felt they had a right to, which is obvious. Yet how does one explain the wholesale killing spree by the jawans whose systematic brutality rivals no less than that of the Pak army in 1971? That is where several causes meet and this is the question that needs most probing. Nor does it explain why the military agencies responsible for security failed to read the situation, no matter what their argument is about their incapacity. While it is true that the intelligence agencies have regularly failed to read most of the situations, whether it was the killing of Sheikh Mujib to Zia to many other sundry revolts, their inability has contributed to a massive carnage of their brother officers and put a strain on national security. Again, as the army is above public accountability, people will probably never know about these issues. But lack of capacity of the most privileged section of the most powerful part of the state enjoying absolute impunity should cause concern. One must address the issue of conspiracies, too. Almost everyone has been blamed for the incident from the Pakistan and Indian intelligence to Islamic extremists. BNP has been mentioned as a party to it to destabilise the AL regime with the usual suspects in the rumour derby (as expected) in the Indian media. AL, too, has been named as a party that wants to weaken the Bangladesh army and ensure its absolute power with no contestant including from the army. Some have also said that AL did it to strengthen Indian hands to enable it to do whatever it wants inside Bangladesh. These speculations will never go away and too many opinions and voices have already been heard and it is possible that the investigation reports will not make everyone happy and many questions will be left unanswered. Perhaps a more cohesive and co-ordinated approach to investigation, had it been possible, would have helped. The Political Context of Rebellion and Deaths This balance of power was possible because civilian political rule has become far more established in the governance system of Bangladesh now. Uninterrupted civilian rule from 1990 to 2007 has certainly borne dividends and it's not an accident that it's being allowed to govern. The result of this growth has been the well-held election of 2008, AL's romp to victory against a discredited BNP, and the delicate balancing act jointly by senior army brass and politicians to manage a situation that could have led to another bloodbath at Pilkhana and maybe even an attempt to corner and push out civilian rule by an angry section of the army. That this has not happened testifies to the maturity of the state and its critical institutions. Yet certain signs are troubling and the news of BDR jawans dying of heart attack, apparently during interrogation, is one. This death in custody is a continuous malady of our law enforcement regime, but does no good to either anyone's reputation or establishing due process. It only enhances the anxiety that some are not answerable to law. Considering that Sheikh Hasina has tried her father's killers in civil courts and continues to follow due process, it is very important, despite obvious temptation, that the current investigation and any subsequent trials be unimpeachable. This is not about personal hurt; this is about the damage that can be caused to the state. Disruption of due process will also disrupt the historical gains made through the alliance of 2008 between the political parties and the military in sharing state power to ensure continuity of elected civilian rule. What needs constant stressing is that while there is a conflict between civilian politicians and the military, the key to the entire argument is the issue of participation of the public, however remotely, in their own governance. That's why there is no substitute possible for elected civilian rule and supremacy of the political regime. Nor is there any reason for the sake of the state to provide extra secrecy cover to the armed forces when it comes to the people's right to know. In fact, it's a guarantee of transparency that must exist in a state institution of the people for whom they exist. Unfortunately, there are words in the air that even the Right to Information Act will exclude the armed forces. This will hardly generate the confidence required for assimilation of all state institutions under a common legal and institutional sky. The Pilkhana incident had many elements that contributed to it, and it was probably progressing towards its dreadful climax over a period of time. Beyond jawan-officer conflict, beyond resentments over never-had-privileges, beyond conspiracies and everything else, it's not a military matter, it's a problem of the republic -- and the republic belongs to the people. Class, Jihadists, and Conspiracies Yet, the unarmed but unruly garments factory workers have risen in rebellion several times, causing heavy damages where the class factor was obvious but conspiracies of foreign agents bent on destroying Bangladesh income were searched for. Even now, people mention garments sector being a target of jihadist attacks, forgetting that the bomb that is brewing is possibly inside the hearts of millions of workers who can't be happy at the state of their own miserable life. If the heart is bitter, instigation is just the fuse. The last few incidents show how fragile the so-called security structure in Bangladesh has been, and that it depends only on law and order tools. Bangladesh risks a repeat in many other sectors if it refuses to take a comprehensive view of security threats. No conspirator has ever succeeded in history without first planting seeds in resentful bitter soil in angry hearts. Bangladesh has had a bad beginning after independence and it has taken several decades to reach a point from which some structural progress can be contemplated. This was validated by the civil-military political relationships of 2008, but, as the Pilkhana incident shows, that alone isn't enough. It's the broader integration of people in the discourse of state construction that is vital for any institution to flourish and prevent bloody carnages. It was true in 1975 and it is still true today. Afsan Chowdhury is presently Research Associate, York Centre for Asian Research, York University. This article first appeared in the April 2009 issue of Forum. 1. Chinta. Farhad Mazhar. "Banned articles." Translated by Naeem Mohaiemen. 1995. (http://www. cyberbangladesh.org/banned.html).

|

What Lies Below

What Lies Below