|

||||||

On a sustainable development trajectory -- Mohammed Farashuddin Steering the economy in 2010 -- Professor Mustafizur Rahman Food Prices and Security Exploding myths, highlighting lessons -- Rizwanul Islam Rising inequality takes shine off growth --M M Akash Rural financing ~ the innovative way -- Khondkar Ibrahim Khaled Participation and representation key to pro-poor planning -- Fahmida Khatun Why list on a stock exchange? -- A.F.M. Mainul Ahsan Pushing agriculture forward -- Dr. Quazi Shahabuddin Policy choices in the FDI domain -- Syeed Ahamed Capital market window to faster growth -- Abu Ahmed Regional Connectivity-Indo-Bangla initiative -- Dr. M. Rahmatullah Foreign banks' lively role -- Mamun Rashid Why regulatory reforms? -- Zahid Hossain Energy management issues -- M. Tamim Jute bubble, lest it bursts! -- Khaled Rab Climate Change Policy Negotiations-Can Bangladesh play a leading role? -- Dr. Saleemul Huq Copenhagen and beyond --Dr. Atiq Rahman Save Bangladesh, save humanity -- Dr A. M. Choudhury For a human rights-based approach -- Dr Abdullah Al Faruque Gender dimension to policy on disaster management -- Mahbuba Nasreen Rainwater harvesting -- Dr. Manoranjan Mondal Environmental degradation and security -- Dilara Choudhury Climatic impact on agriculture and food security -- Prof Zahurul Karim PhD Monoculture destroys coast and forests --Philip Gain Towards a strong adaptation strategy -- Md. Asadullah Khan Biodiversity conservation: Challenge and opportunity -- Mohammed Solaiman Haider Grameen Shakti's renewable energy role -- Abser Kamal

|

||||||

Pushing agriculture forward Dr. Quazi Shahabuddin

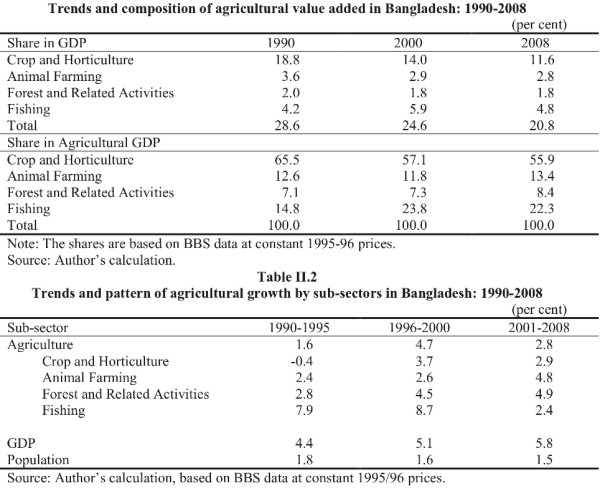

Review of agricultural growth performance and past policies The pattern of agricultural growth, disaggregated by sub-periods and sub-sectors is presented in Table II.2. An examination of the growth rates by sub-periods reveals that although both GDP and population displayed upward and downward trends respectively, agriculture exhibited fluctuating growth over the 1990-2008 period. Agriculture grew at a rate of only 1.6 per cent during 1990-95, which was lower than the population growth during the period. However, the growth rate picked up significantly (4.7 per cent) during 1996-2000, though it has declined to 2.8 per cent in the current decade (2001-2008). This can largely be attributed to significant acceleration in growth of crop and horticulture during 1996-2000. In fact, this sub-sector registered negative growth during the first half of the 1990s.

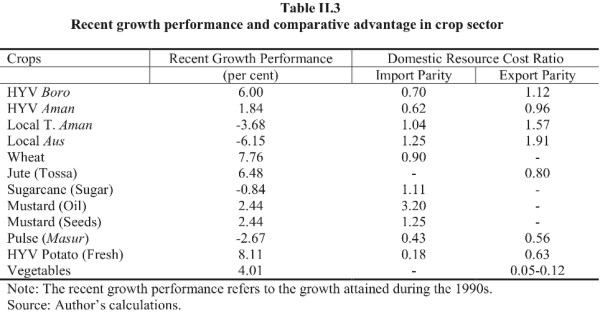

Foodgrain production Non-rice crops The production of these minor crops needs promotion to reduce import dependency, if not for complete import substitution. Moreover, these crops provide substantial opportunities for value addition after processing and for creation of employment opportunities in the rural areas. Several studies of comparative advantage demonstrate that considerable scope exists for crop diversification through promotion of non-rice crops in Bangladesh. It may be interesting to examine whether the actual growth performance of different crops is consistent with the comparative advantage of producing these crops domestically, either for import substitution or for export. These are shown in Table II.3. It is observed that except for pulses and oilseeds, the crops (such as HYV boro, HYV aman, wheat, jute, potato and vegetables) with DRC ratio of less than unity displayed positive and mostly significant growth performance, while those with greater than one (such as local aman, local aus and sugarcane) registered negative growth during the 1990s. Thus, the production growth pattern is observed to be largely consistent with the comparative advantage as reflected in the estimated domestic resource costs ratio, thereby indicating land allocation pattern conforming to the resource endowment of the country.

Non-crop agriculture Review of past policies The sector-specific policies in agriculture evolved around the dissemination of modern technologythe so-called 'Green Revolution'with direct involvement of the public sector. The Bangladesh Agricultural Development Corporation (BADC) had a virtual monopoly in procurement and distribution of fertiliser, seed, pesticides and minor irrigation equipment in the country. The Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWBD) implemented large scale surface water irrigation, flood control and drainage projects. With economic reforms, liberalisation of input and output markets became the dominant feature.

The markets for other agro-inputs such as power tillers and pesticides were also liberalised. The deregulation of agricultural pricing and distribution policies and abolishing public monopoly in food grain trade provided positive incentives to the private traders and farmers. The changes in policy regime contributed to increased production while prices of irrigation equipment and other input declined, and ownership of irrigation equipment for all categories of farmers increased with no clear evidence of adverse distributional consequences. The reforms in agriculture led to reduced price distortions which encouraged the farmers to take more rational decision, with respect to both input use and crop production. The anti-rural bias in economic incentive structure declined through adjustments in exchange rate, lowering of the rate of protection for import-substituting industries, reduced dispersion of tariff structure and reduction of tariff anomalies. It is important, therefore, to pursue further reforms to remove existing distortions that will encourage increasing production and exploiting export potential of crops having comparative advantage. Similarly, reform measures aimed at deregulation, privatisation and liberalisation of trade and marketing structure in agriculture led to increased fertiliser use along with adoption of HYVs and investments in irrigation and other agricultural equipment. Although these reforms contributed to accelerated growth, further liberalisation of markets and production processes is needed to ensure increased use of modern input and better performance of input and output markets. The government needs to adopt a clear and time-bound strategy and policies to implement the reform agenda to ensure more effective participation of the private sector. Emerging challenges It may be mentioned here that Bangladesh has prepared two Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSP) in the current decade. The first PRSP (2004-2006) rightly recognised agriculture as an essential component, in fact, a prime mover in the quest for more equitable and pro-poor growth. The projected rate of economic growth implied an agricultural growth of 4.5 per cent, which is higher than what the sector has actually attained in recent years. One may, therefore, ask whether is it possible to attain and more importantly, sustain such a growth in agriculture in the future? Also, what does it imply in terms of growth of different sub-sectors and associated policies and programmes? Agriculture has been the main source of food in Bangladesh. However, domestic production has to be supplemented by imports mainly of cereals such as rice and wheat, but also of other essential food such as edible oil, sugar and dairy products including milk powder. The demand for all these food products will continue to grow due to both population growth and growth in income. Against this rising demand, the availability of land for growing food is dwindling fast, as mentioned above. This implies that an increasing agricultural output including food has to be coaxed out of an ever-declining area of land to meet the growing demand unless imports on a vast scale is contemplated, which may not be a feasible option for Bangladesh. One of the most serious challenges that Bangladesh agriculture will have to face is the adverse impacts of climate change. What might happen in the not-too-distant future (some would argue that the uncertainties have already begun on the ground as problems of pollination in wheat and early or immature flowering of rice have been reported in 2009) are that the water regime may drastically change with years of too much abundance (heavy floods) and too little (severe droughts) with greater frequency than before. Sea level will rise, although how fast and how far it would submerge the land along the coast remains debatable due to the coastal defences in the form dykes and polders. Salinity levels would, however, increase and so will the frequency and severity of coastal cyclones and storm surges. It may be noted here, however, that the implications for agriculture are not something completely different from what these may be under a situation without climate change. The implications for research and technological change to develop new varieties are logically the same. The only new thing that comes up is the urgency of necessary actions. The technological change that has taken police in agriculture, particularly in crop production so far has been the development and dissemination of high yielding varieties which need controlled water, are fertiliser responsive but may be susceptible to various diseases and pest attack. Upto 2001, the rice research system had released 47 improved rice varieties. Several refinements have also been made to the HYV profile over time. These include the development of pest and disease resistant varieties, better yielding varieties and most importantly, shorter maturity variety, particularly suited to aman cultivation. There are also newly developed boro HYVs which are somewhat lower-yielding but can be harvested 3-4 weeks earlier than the normal boro harvesting time. Some limited success has also been achieved in developing varieties suited to specific ecological conditions such as those resistant to salinity. However, all of these still have two basic characteristics inherited from the earlier ones. These need chemical fertilisers and controlled water regime related to irrigated land. In the near future, therefore, the issues related to fertiliser availability and use, pricing and subsidy, as well as pricing and policies facilitating irrigation, given the dominance of boro in total rice production, remain critical. In particular, the issues of subsidy for fertilizers as well as for diesel and electricity for irrigation has become immediate policy concerns.

Concluding remarks The production system in the crop sub-sector continues to be dominated by rice. Once the foodgrain deficits are met, rice should give way to other higher productive and more profitable crops. As mentioned earlier, several studies suggest that except for a few import-competing crops such as sugarcane and oilseeds, Bangladesh has comparative advantage in the production of most agricultural crops. The exploitation of this potential will, however, depend on investment for developing infrastructure for storage, processing, marketing and financial services, for which public support is needed. Investment for reliable supply of power to rural areas, development and maintenance of an efficient transport network, and modern communication facilities for low-cost and timely exchange of information is crucial. The development of infrastructure will also reduce the cost of processing, storage and marketing of fisheries and livestock production, which may encourage private sector investment in these activities. An important area in which public sector must continue to be involved is agricultural research, education and training for generation of knowledge, information and technology. The world is currently witnessing a major revolution in biotechnology. We need to develop infrastructure and skills to access those technologies to adapt them to suit our needs. In the field of agricultural research, we need to assess the balance in investments for basic and strategic research versus adaptive and applied research on the basis of technologies available from international research centres. In response to changing pattern of demand, the future strategy for agricultural growth must contain elements to promote non-cereal crops and fish and as well as livestock production. Faster development of livestock and fisheries may promote both equity and food security by focusing attention on disadvantaged social groups and regions where the crop production environment is unfavourable. The promotion of rice-fish cropping system in the deepwater floodplains and saline-affected coastal areas (the areas bypassed by the Green Revolution) could help improve economic conditions of the rural poor, particularly in less developed regions in Bangladesh. Because of severe land constraints, sustainability of growth in crop production in the 21st century will depend on the government's continued support for agricultural research to further develop technologies and improved farming practices and on its efforts to disseminate these technologies to the farmers. Technological progress in rice and wheat has reduced the competitiveness of pulses and oilseeds and the area under these crops has continued to decline. Research on these crops must be intensified. A system approach has to be taken for broad-based agricultural research that requires collaboration and coordination among various research institutions. Bangladesh needs to face the challenges of exploiting the emerging global opportunities. Within the general thrust of UR Agreement, the WTO rules provide several opportunities which Bangladesh agriculture can capitalise through policy actions. Under the Agreement on Agriculture (AoA), Bangladesh as least developed country is exempted from reduction commitments on tariffs, export subsidies and domestic support to agriculture. Although Bangladesh reported bound tariffs at 200 per cent for all agricultural products, operating tariffs at present are much lower. The price distorting and indirect supports to agriculture are also minimal and domestic support is negligible. In fact, Bangladesh has the option to increase support to agriculture without violating the provision of WTO. To conclude, agriculture has undergone major structural changes and achieved major successes in Bangladesh over the last four decades. Despite many problems and constraints, a quiet agricultural revolution has taken place that has enabled the country to achieve its national food security targets in the production of food grains. Agriculture continues to evolve in response to numerous factors, including natural calamities, sociopolitical changes, population growth, urbanization, new technology, opportunities in the rural confirm sector, and commercialisation. Government macroeconomic, trade, and agricultural pricing policies have played a major role in shaping price incentives in production and consumption and will continue to be important determinants of agricultural growth. Policies aimed at increasing production and stabilizing prices need not rely mainly on price subsidies or substantial increases in public stocks, however. Indeed, productivity-enhancing investments in agricultural research and extension, improvements in post harvest management and agro processing, and investments in market infrastructure can complement agricultural price and trade policies and enable rapid agricultural growth and higher farmer incomes even in a context of shifting world prices. Dr. Quazi Shahabuddin is a Former Director General BIDS, Dhaka.

|

||||||

© thedailystar.net, 2010. All Rights Reserved |