How fares the Bangladesh economy?

Rizwanul Islam

|

Photo: Star |

In March 2011, Bangladesh is going to celebrate the fortieth anniversary of its independence. It may be a good occasion to take stock of how the economy is doing at this occasion. While the health of the economy is important from the point of view of the living conditions of the people that comprise the nation, it is important to look at it due to another reason. It may be recalled that alongside political and cultural subjugation of Bangladesh (the then East Pakistan) by the western wing of the country of which it was part at that time, growing economic disparity between the two provinces provided a powerful motivation behind the movement for independence. When Pakistan was created, Bangladesh not only started as the poorer of the two provinces but was also deprived of the means for narrowing the gap. After gaining independence, the country became a full member of the community of nations and was able to pursue its policies independently. Hence it may not be unreasonable to look at how the Bangladesh economy has been doing not only in absolute terms but also in relation to that of others, especially of its neighbours in South Asia. This is especially so because when the country gained independence, suspicion was expressed in various quarters about its economic viability, and it was even dubbed as an international basket case. It is against this backdrop that the present article looks at the country's performance on the economic front in a comparative South Asian perspective. I should like to mention at the outset that a vast and complex topic like this cannot be treated adequately in the space of an article of the present kind and would like to suggest further work in the area.

2. Economic growth

In terms of growth of Gross Domestic Product (GDP _ which represents the sum total of all goods and services produced within a country during a given period), Bangladesh economy did not have much to boast about during the 1970s and the 1980s, but achieved acceleration in growth during the 1990s and the 2000s. While the annual average growth during the 1980s was less than 4 per cent, it exceeded 4 per cent in the early 1990s and crossed the 5 percent mark during the second half of that decade. Since 2004, annual rate of GDP growth has been over 6 per cent. But that trend got reversed in 2008-09 and 2009-10 _ first due to a series of natural calamities and then due to the adverse effects of the global economic crisis of 2008-09. However, the potential of the economy of Bangladesh to achieve GDP growth of over 7 per cent is widely recognized.

Along with a decline in the country's population growth, the acceleration of GDP growth resulted in a substantial increase in the growth of the country's per capita income. While the annual per capita GDP growth was less than 3 per cent per annum till the mid-1990s, it crossed 4 per cent during 2000-09. For a country that was once dubbed as an international basket case, this is no mean achievement. However, before going further on economic growth and per capita income, it may be useful to bring in the comparative perspective mentioned above. Table 1 presents some basic figures in that regard.

Along with a decline in the country's population growth, the acceleration of GDP growth resulted in a substantial increase in the growth of the country's per capita income. While the annual per capita GDP growth was less than 3 per cent per annum till the mid-1990s, it crossed 4 per cent during 2000-09. For a country that was once dubbed as an international basket case, this is no mean achievement. However, before going further on economic growth and per capita income, it may be useful to bring in the comparative perspective mentioned above. Table 1 presents some basic figures in that regard.

The data presented in Table 1 start from 1992 because an earlier study by noted economist Azizur Rahman Khan pointed out a widening of gap in per capita incomes between Bangladesh on the one hand and India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka on the other during 1970-1992. If one extends the comparison beyond the 1990s and looks at the figures for 2008, one observes a further widening of the difference between Bangladesh and all the other three countries. In 2008, India's per capita income was more than double that of Bangladesh, although in 2005 it was only 53 per cent higher. The gap between Bangladesh and Pakistan narrowed somewhat between 1992 and 2005, but since then has widened again and in 2008 was wider than it was in 1992. This implies that during the entire period of 1970-2008, the gap between Bangladesh and Pakistan could not be reduced. The same is the case with Sri Lanka: in 2008, that country's per capita income was three and a half times that of Bangladesh, while in 1992 it was two and a half times only.

|

Photo: Rashed Shumon |

In fact, there have been several periods of rapid growth in South Asia as a whole. The first was during the 1980s when Bangladesh was not able to accelerate its growth significantly. The second has been during the 2000s when Bangladesh was also able to raise its GDP growth, but others, especially India did even better. In fact, Pakistan's growth faltered somewhat during the 1990s, as a result of which the gap between Bangladesh and that country narrowed during 1992-2005. But Pakistan's economy regained momentum in the 2000s, and there was a reversal of the narrowing of the gap. Data on the rates of GDP growth achieved by selected countries of South Asia since 2000 are presented in Table 2.

India has clearly been ahead in the league table based on annual GDP growth during 2000-08. At the other end lies Nepal whose economic growth continued to suffer. While India finally started to reap the benefits of economic reforms introduced in the early 1990s, Nepal's disappointing performance could perhaps due primarily to the political conflict that has affected the country for some time. However, Sri Lanka's economy has been able to do well despite the armed conflict that continued. Pakistan's economy also emerged from the period of low growth and was able to achieve healthy growth. While GDP growth of Bangladesh during 2000-08 was marginally higher than that of Pakistan and Sri Lanka, it was substantially less than that achieved by India. Thus, it is not surprising that the gap in per capita income between these two countries widened.

Acceleration in economic growth in Bangladesh was possible due to acceleration in the rate of investment as well as domestic savings. During the entire decades of the 1970s and 1980s, domestic savings and investment stagnated at low levels. During 1995-96 to 2009, domestic savings increased from 14.9 per cent of GDP to 20.1 per cent. Investment rate (as percentage of GDP) increased from nearly 20 per cent to 24 per cent. Despite this increase, investment rate remains lower than in other South Asian countries except Pakistan. In 2009, India's investment rate was 35 per cent while that of Nepal and Sri Lanka was 30 and 25 per cent respectively. Pakistan's investment rate in 2009 was only 19 per cent _ much lower than in other South Asian countries.

Acceleration in economic growth in Bangladesh was possible due to acceleration in the rate of investment as well as domestic savings. During the entire decades of the 1970s and 1980s, domestic savings and investment stagnated at low levels. During 1995-96 to 2009, domestic savings increased from 14.9 per cent of GDP to 20.1 per cent. Investment rate (as percentage of GDP) increased from nearly 20 per cent to 24 per cent. Despite this increase, investment rate remains lower than in other South Asian countries except Pakistan. In 2009, India's investment rate was 35 per cent while that of Nepal and Sri Lanka was 30 and 25 per cent respectively. Pakistan's investment rate in 2009 was only 19 per cent _ much lower than in other South Asian countries.

Bangladesh has also made notable achievements in other macroeconomic aspects like keeping inflation under control, budgetary deficits to acceptable levels, ratio of external debt to GDP at low levels, and raising foreign exchange reserves to a healthy level. As for the latter, it may be noted that only in recent years has the level exceeded the requirement for three months' import bill (which is generally regarded as the minimum required). In 2009-10, the level of reserves rose to over six months' import bill. While this is better than Pakistan's (5.2 months in 2009-10) and Nepal's (3.7 months in 2007-08), it is much lower than India's (11 months in 2009-10).

How was the economy of Bangladesh affected by the global economic crisis of 2008-09 compared to other countries of South Asia? In terms of GDP growth, Bangladesh appears to have been affected much less than India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka (Table 2). While India's GDP growth suffered a sharp decline in 2008 and recovered a bit in 2009, Pakistan's GDP growth declined sharply in 2008 and the decline continued in 2009. Sri Lanka appears to have been hit with a lag _ in 2009. In comparison, the impact on growth in Bangladesh has been much more muted.

How was the economy of Bangladesh affected by the global economic crisis of 2008-09 compared to other countries of South Asia? In terms of GDP growth, Bangladesh appears to have been affected much less than India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka (Table 2). While India's GDP growth suffered a sharp decline in 2008 and recovered a bit in 2009, Pakistan's GDP growth declined sharply in 2008 and the decline continued in 2009. Sri Lanka appears to have been hit with a lag _ in 2009. In comparison, the impact on growth in Bangladesh has been much more muted.

3. Points of concern in the area of economic growth and macroeconomic performance

Despite satisfactory rates of economic growth and macroeconomic performance achieved by the economy of Bangladesh over a period of time, a few points of concern remain.

The gap in per capita income between Bangladesh and other South Asian countries like India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka has widened over time.

There has been a slowdown and a secular decline in GDP growth rate after 2005.

Growth in agriculture has suffered from instability in the past. It is only in recent years that growth in this sector appears to have stabilized and has become satisfactory.

|

Photo: Star |

Growth in manufacturing picked up in the early part of 2000s and achieved a peak of nearly 10 per cent per annum in 2006. But after that it has declined and settled to a little over 6 per cent per annum. This trend is disconcerting because high growth of manufacturing is essential from the point of view of achieving a transformation in the structure of economy that would enable transfer of labour from low productivity agriculture to sectors with higher productivity and earnings. In countries of East and South East Asia (e.g., South Korea and Malaysia) that succeeded in this regard, manufacturing industries grew at approximately double the growth of GDP. In order to achieve that pattern of growth, manufacturing industries in Bangladesh would need to grow at annual rates of about 12 per cent per annum. Although Bangladesh has witnessed the emergence of some new industries other than ready- made garments (e.g., ceramics and shipbuilding), the size of these sectors are still too little to make a real difference. Currently, structural change in Bangladesh appears to be driven more by the service sector.

Although the rate of investment has grown, it seems to have tapered off and stabilized around 24 per cent of GDP. The examples of high growth economies like China and India show that this needs to increase substantially. While domestic savings and investment need to increase, foreign direct investment (FDI) is also important. The success of Bangladesh in attracting FDI appears to have been limited (especially compared to India and Pakistan).

|

Photo: Palash Khan |

Foreign exchange earnings are heavily dependent on two items of export, viz., ready-made garments and manpower. An adverse effect on either could lead to a quick erosion of the success achieved in this regard and could create pressure on the country's current account balance. Manpower export has already started to decline since 2009 and the growth of remittances has declined sharply in 2010.

The vulnerability of the macroeconomic situation is indicated by the fact that although the government declined IMF's assistance only in April 2010, it reversed that position before the end of the year to accept a loan of US$1 billion with its associated conditionalities.

4. Poverty reduction and human development

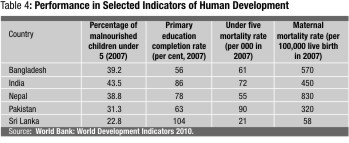

Economic growth and per capita income provide only part of the story about success on the economic front. High rate of economic growth is only a means to the important goals of reducing poverty, improving conditions of living of the people in general and achieving shared prosperity. In that context, it would be important to examine the degree of success in reducing poverty and achieving other Millennium Development Goals. Some relevant data are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

As for the fight against poverty in Bangladesh, 1970s and 1980s may be regarded as lost decades because the incidence of poverty (the proportion of people living below a poverty line that is defined in terms of a level of income needed to meet certain basic needs of life) actually increased during the first decade and fluctuated in the second. Only in the 1990s, poverty started to decline on a sustained basis and came down from nearly 59 per cent in 1991-92 to 40 per cent in 2005. For 2009, the Planning Commission (in its revised PRSP II) projected the incidence of poverty to be between 31.1 and 32.5 per cent. But that is based on the assumption of unchanged relationship between economic growth and poverty reduction. However, given the sharp increases in prices of food grains during 2007-08 and the adverse effect of the global economic crisis during 2008-09, the relationship between economic growth and poverty reduction may not have remained unchanged. One exercise by the World Bank suggested that the shocks mentioned above could have reduced the decline in the incidence of poverty by two percentage points. This implies that instead of 32 per cent, the incidence of poverty in 2009 could be 34 per cent.

In order to achieve the MDG of poverty reduction (i.e., to reduce poverty to half the level of 1990), the incidence of poverty in Bangladesh would have to be 29.5 per cent in 2015. If poverty in 2009 has really declined to 34 per cent, the country would need another decline of 5.5 percentage points during 2009-15. If the country can maintain its present growth rate of about 6 per cent per annum, it should be possible to attain the MDG 1 of poverty reduction. However, given the rise in inequality that has been witnessed in recent years and the adverse effects of the external shocks during recent years, I have argued elsewhere that the economy would need to grow at more than 6 per cent per annum in order to be able to achieve the MDG of halving poverty by 2015.

In order to achieve the MDG of poverty reduction (i.e., to reduce poverty to half the level of 1990), the incidence of poverty in Bangladesh would have to be 29.5 per cent in 2015. If poverty in 2009 has really declined to 34 per cent, the country would need another decline of 5.5 percentage points during 2009-15. If the country can maintain its present growth rate of about 6 per cent per annum, it should be possible to attain the MDG 1 of poverty reduction. However, given the rise in inequality that has been witnessed in recent years and the adverse effects of the external shocks during recent years, I have argued elsewhere that the economy would need to grow at more than 6 per cent per annum in order to be able to achieve the MDG of halving poverty by 2015.

How does the poverty reduction record of Bangladesh compare with that of other countries of South Asia? Data based on national poverty line are presented in the second and third columns of Table 3 and figures based on international poverty line are in the fifth and sixth columns.

If one uses the international poverty line (which is appropriate for comparing across countries), Bangladesh appears to be the country with the second highest incidence of poverty (Nepal showing the highest incidence of poverty). Second, figures based on national poverty line show that the rate of poverty reduction in Bangladesh and Nepal has been higher than in other countries. The figures based on international poverty line are available for a shorter period; but they also show Bangladesh (and Nepal) to have had a higher rate of poverty reduction compared to India and Sri Lanka. As for the latter, it needs to be noted that the absolute level of poverty in that country is much lower compared to other countries. It is, therefore, possible that further reduction of poverty from that level would be at a slower rate.

|

| Photo: Don Bishop |

Another important area of concern is the rise in inequality in the distribution of income. While this issue is important from the point of view of achieving shared and inclusive growth, it needs to be remembered that a rise in income inequality reduces the effectiveness of economic growth in reducing poverty. In Bangladesh, there has been an increase in the degree of inequality in income distribution from the mid-1980s. While the rise was gradual till the early 1990s, it has become faster since then. Of course, a similar tendency may be observed in other countries of South Asia (especially in India and Sri Lanka). And that implies that there is something in the strategy of economic growth pursued by these countries that is responsible for this undesirable outcome. On the other hand, the experience of economic growth in some countries of East and South East Asia (especially Republic of Korea from the 1960s to the 1970s and Indonesia from the1970s to the 1990s) shows that it is possible to avoid a rise in inequality without compromising on economic growth. It would be useful to look at such experiences from the point of view of developing strategies for more inclusive growth.

The data on poverty presented above refer to what is known as “income poverty” (i.e., estimate of poverty based on income criterion); and it would be important to go beyond that to see how the countries are doing in terms of other indicators of human development, viz., education and health. Some relevant data are presented in Table 4.

If one uses the rate of completion of primary education as the indicator of progress in education (as opposed to simple enrolment because a vast proportion of those enrolled tend to drop out), Bangladesh appears to be at the lowest level with only 56 per cent completing that level. In terms of reducing child mortality, the performance of Bangladesh has been commendable. The level of Bangladesh in that regard is better than that of India and Pakistan, but is way behind Sri Lanka. But Bangladesh has not been equally successful in reducing maternal mortality. The rate in Bangladesh is lower only compared to Nepal, and is higher than India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. So, there is a lot to do on that front as well. In terms of child malnutrition also, the performance of Bangladesh is not very impressive; Pakistan and Sri Lanka has done better.

|

Photo: Iqbal Ahmed |

On the whole, in the area of poverty reduction and human development, although Bangladesh has made notable progress, the performance remains somewhat mixed, and there is no scope for complacency. Even considering the fact that Bangladesh started its journey as an independent nation with a very high incidence of poverty, over 50 million people remaining poor and about 32 million suffering from acute poverty after forty years of independence is not at all a comfortable and respectable situation.

5. How employment-friendly has economic growth been in Bangladesh?

Why does one need to look at the employment performance of the economy in addition to growth and poverty reduction? The simple answer is that this is an important means of translating the benefits of economic growth into poverty reduction and of achieving shared and inclusive growth. Theories of development of economies with surplus labour and a dual economic structure (i.e., the economy consisting of a small modern part and a large traditional part) point out that the process of development involves a transfer of labour from traditional economic activities characterized by low levels of labour productivity to modern sectors with higher productivity. In order for such transfer to take place sufficiently rapidly so as to exhaust the surplus labour in the traditional sector in the shortest possible time, modern sectors have to absorb labour at high rates. There lies the importance of the rate at which modern sectors generate employment. They need to achieve rapid growth of output and employment simultaneously. What has been the record of Bangladesh in this regard?

During the forty years after independence, the country has seen a significant degree of change in the sectoral composition of employment. As positive developments, one can easily mention the three million or so workers (most of whom are women) engaged in the ready-made garment industry, although there are question marks surrounding the conditions of work in the sector. One may also talk about other industries like leather products, furniture making, ceramics, shipbuilding, etc. While some are traditional others are emerging and have shown potential for growth. One may also talk about the growth of service sectors like trade, finance, telecommunication, etc. But the real question is: what do all of them add up to?

|

Photo: Dieter Spannknebel |

The share of agriculture sector in total employment has declined over time, but the share of manufacturing sector has not registered a corresponding increase. In fact, during the past two decades, the share of manufacturing has increased only slightly (from about 10 per cent in 1999-2000 to 11 per cent in 2005-06). In this context, it may be useful to look at some figures. In Bangladesh, approximately 2 million persons join the labour force every year. The manufacturing sector is currently capable of absorbing less than 250,000 persons (or around 13 per cent of the annual addition). The rest are absorbed either in agriculture (about 737,000, or 42 per cent), construction, and services of various kinds. In fact, the structure of employment in Bangladesh is becoming more service sector oriented. While some of the service sector activities belong to the modern sector, the vast majority of them fall within the traditional sector. In other words, the modern sectors of Bangladesh are not absorbing labour at sufficiently high rate. In fact, the vast majority of workers in Bangladesh are engaged in the so-called informal sector.

Another point of concern is the decline in the ability of the economy to create employment. It needs to be noted that apart from special employment programmes (which should be seen as temporary measures), employment is created in the process of production. By the ability of an economy to create employment, we mean the rate of growth of employment in relation to the rate of output growth. In Bangladesh, during the 1980s, one per cent growth in GDP was associated with an employment growth of 0.55 per cent. During the 1990s, this went down to 0.495 per cent. The manufacturing sector also witnessed a decline in the employment intensity of growth during the 1990s compared to the 1980s. Data for the period of 2000s are not yet available. Given the rapid growth of ready-made garment industry, one may expect a reversal of the above-mentioned trend. But growth of only one such sector is not enough to fully meet the challenge of growth of productive employment in the modern sector. A few more sectors (e.g., furniture, ceramics, shipbuilding) have been registering growth in recent years. But the base of such industries is so low that it will take some more years of high growth for them to be able to make a real difference to the overall employment growth.

Some other points of concern in relation to employment include the following:

A general absence of social protection measures (e.g., protection against old age, ill health, unemployment, etc.) except small programmes with limited coverage

A plethora of social safety net programmes without an overall strategy and vision

Absence of severance pay in many sectors of the economy in case of retrenchment of workers

Absence of an active labour market policy that would include retraining of workers to match changing skill requirements of the economy and to respond to retrenchments during periods of economic downturns, facilitation of re-deployment of workers, etc.

Concluding observations

Bangladesh economy has the potential to achieve higher growth than has been achieved in the recent past; and effort needs to be made to attain and sustain such growth. That, in turn, would require serious efforts at removing the constraints on investment _ domestic as well as foreign. Mobilization of domestic resources (especially raising revenue/GDP ratio) should be a priority. However, single-minded pursuit of a growth agenda would not be sufficient from the point of view of achieving the ultimate goal of development, viz., reduction (and eventual elimination) of poverty and achievement of other Millennium Development Goals through a wider sharing of the benefits of growth. Higher rate of growth of productive employment, a faster transfer of workers to sectors/activities with higher levels of productivity, reversal of the trend of rising income inequality, and greater attention to social aspects of development would have to be important elements in a “growth plus” development agenda.

The author, an economist, is former Special Adviser, Employment Sector, International Labour Office, Geneva.