The

issue is democratic

culture

Emajuddin

Ahamed

........................................................

FOR

the first time in history there are

more democratic states in the world

than autocracies, but democratic culture

is still in short supply. Unless it

grows in right proportion, democratic

order may not thrive and blossom forth

in every nook and corner of the globe.

Democratic culture is indeed the life

blood of democratic system. Both should

go together.

Look

at the 2001-2002 Survey of Freedom

House report, you will find that at

this point of time in history more

than 65 per cent of the world's population

live in free or partly free states.

It has shown that of the world's 192

states (members of the UN) 121 (63

per cent) are electoral democracies

while in 1987 only 66 out 167 states

(40 per cent) were in this category.

According to one estimate of the UNO,

81 countries of the world have taken

significant steps in democratization

of their political system since 1980,

with 53 military regimes replaced

by civilian governments. There has

been largescale replacement of military

dictatorship in Latin America, emergence

of new democracies in Central and

Eastern Europe and establishment of

democratic regimes in Africa, South

and South-East Asia.

Look

at the 2001-2002 Survey of Freedom

House report, you will find that at

this point of time in history more

than 65 per cent of the world's population

live in free or partly free states.

It has shown that of the world's 192

states (members of the UN) 121 (63

per cent) are electoral democracies

while in 1987 only 66 out 167 states

(40 per cent) were in this category.

According to one estimate of the UNO,

81 countries of the world have taken

significant steps in democratization

of their political system since 1980,

with 53 military regimes replaced

by civilian governments. There has

been largescale replacement of military

dictatorship in Latin America, emergence

of new democracies in Central and

Eastern Europe and establishment of

democratic regimes in Africa, South

and South-East Asia.

The progress has been slowest in the

Middle East in the Arab World with

only four out 17 countries with multi-party

electoral systems. Democratic order

came back, as suggested ably by Huntington

in his The Third Wave: Democratization

in the Late Twentieth Century, in

such countries as Pakistan, Nepal

and Bangladesh in South Asia during

the last decade of the last century.

The

growth of democracy is however not

unilinear in the sense that it goes

on developing. The wheel of democratic

order turns back if democratic culture

fails to keep pace with it. In the

1990's some such new democracies as

Sierra Leone, Belarus, Cameroon, Uzbekistan,

Pakistan, have, instead of having

stabilized, reverted to authoritarianism.

Quite a good number of new democracies

are fumbling and faltering, and some

of them quite dangerously dangling

near the crevice of authoritarianism.

How one can explain this phenomenon?

Linz and Stepan (1996) have argued

that for stability of democratic order

in a society five inter-related conditions

must be fulfilled: (a) a free and

lively civil society; (b) a relatively

autonomous political society; (c)

rule of law guaranteeing citizens'

rights and independent associational

life; (d) an institutionalized economic

society; and (e) functioning state

bureaucracy. But as I feel and feel

very strongly that above everything

else democracy becomes consolidated

is a society in situations where "those

competing for power play by its rules".

In other words, democracy becomes

stable only if it is ably supported

by democratic culture, which is another

name for rules of the all important

political game. If the political activists

do not go by rules of the game, the

prospects of stabilization of democratic

order are dismal and bleak.

Bangladesh

is one of those new democracies where

democratic culture is yet to strike

deep roots into the social soil. Institutional

framework has been created, but these

institutions have not been vibrant

with life forces. Scores of political

parties exist in the country, but

all of these are organized on feudal

lines rather than democratically,

thus creating ample opportunities

for personalized power for the party

bosses. The Jatiya Sangsad, comprising

members directly elected by the people,

exists in Bangladesh, but this is

yet to be the centre-piece of national

polities.

Most

often the crucial decisions affecting

interests of the people are taken

outside the Sangsad. The ministry

consisting of the representatives

of the people operates here but the

principle of ministerial responsibility

is not in sight. Local government

has not yet been functional in the

country and most often the local governing

bodies are working as support bases

of the sitting government.

True

it is that Bangladesh has achieved

some success during the last decade.

The institution of election has been

rehabilitated at last in 1991 as the

mode of peaceful transfer of power

to the victorious party or parties.

This has been institutionalized through

the Non-Party Caretaker Government

for conducting the general election.

A few conditions which are essential

for effective functioning of democratic

government are either fulfilled or

are in the process of being fulfilled.

The press is more or less free. Attempts

are on to institutionalize the independence

of judiciary. The civil society is

being lively day by day.

Despite

all these, the political situation

seems to slide downhill. Even after

three decades democracy in Bangladesh

exists mainly in hope rather than

in reality. To most people of this

country, democracy is more like a

rosy ideal an aspiration cherished

by the people in the thickets of big

money and muscle-oriented political

exercises, dominated by a small group

of privileged ones. The argument of

force has not yet been replaced by

the force of argument.

Democratic

culture, which helps build consensus

among the politically relevant social

sectors including the political parties,

is yet to get off the ground. Tolerance

among the political activists is conspicuous

by its absence. The consensual approach

involving mutual give and take, being

respectful to one another's views

and the overriding concern of the

majority party to work together with

the minor ones is yet to be effective.

The party in-power tends to ignore

the opposition and the opposition

goes on opposing anything and everything

the party-in-power proposes. Politics,

in consequence, has been confrontational

and the social forces have been fragmented

and divided, thus making it very difficult

for any government to build consensus

behind any developmental agenda. When

politics becomes confrontational,

partisanship becomes intense. That

leads to immunity for the party followers

even for their worst excesses and

corrupt practices, and vengeance to

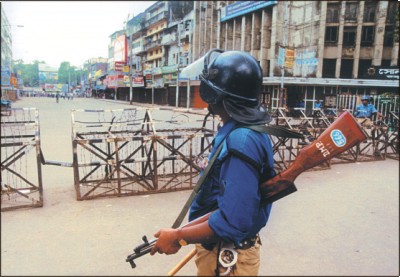

the opponents. Since the Jatiya Sangsad

fails to absorb the demands of the

members of the opposition political

parties, politics comes down to the

stormy streets in the form of processions

and demonstrations. Occasional hartals

keeps the shops, work centres, business

houses, offices and educational institutions

closed, thus affecting law and order

in the country seriously. Politics

in the process gets transformed into

power-politics and democratic values

get dissipated.

In

new democracies, distorted democratic

culture affects both the polity and

political activists. Polity becomes

power-oriented in the sense that power

turns out to be the motive force at

every layer of administration. The

political activists, on the other

hand, become motivated to use political

power as the medium of power, influence,

and in some cases property for mobilizing

more power in their baskets. In Bangladesh,

democratization has taken the form

Prime Ministerial leadership. In the

developed West, Prime Ministerial

leadership is based on collegial equality.

Prime Minister is the team leader

Primus inter pares first

among the equals. He rules because

both of his colleagues and counterparts

allow him to rule.

He

has no right to command. He acquires

it daily by his work and prestige

over his colleagues. In our country

the Prime Ministerial leadership has

given rise to strong executive leadership.

The Prime Minister is not only the

head of the government but also the

head of the party, resembling authoritarian

executive. Since there is very little

trust in the system, nobody trusts

anyone and everyone looks to the Prime

Minister not only for guidance but

also for shelter thus leading to hierarchical,

position-based leadership, making

"him or her monarch of all he

or she surveys".

Democracy

by any definition, is a limited government

limited by the rights of people and

by normative overtone of democratical

culture. When democratic culture gets

distorted democratic government loses

much of its salt and comes closer

to what we have seen in Bangladesh

during the last decade a government

by the Prime Minister with the help

of a limited number of confidants

mainly to serve the predetermined

interests of a small group rigidly

bound together by the cements of petty

personal goals.

Democratic

culture, which keeps democratic order

vibrant, is lifeless not only in the

polity of Bangladesh but also the

political parties, both in position

and opposition.

.........................................................

Author is former vice-chancellor,

Dhaka University, and advisor caretaker

government.