The

rule of law

How

distant is the dream!

M

Abdul Hafiz

...................................................................

While

passing on to us the 'white man's

burden' the law givers of our colonial

vintage bestowed on us a great inheritance

-- an elaborate legal framework and

a long history of legal tradition.

But then, like in most other developing

countries where a civil society and

democracy are still in embryonic stage

the governance is essentially the

exercise of state power through its

integral organs to achieve the state's

overall objective. And so are its

application of legal system. So, universal

arrangements did not quite work satisfactorily

in our country due primarily to inadequacy

of political morality expected of

our leaders who in turn seized power

to run the affair of our country.

They took for granted the state-endowed

crude power bereft of its moral content

for ensuing public obeisance to their

rule.

This

could have worked for a while but

often backfired bringing to question

the government's authority to rule

with stained hand and tainted image.

The public did not appear prepared

to accept in silence the government's

double standard of law and its application,

myriad dichotomies in the political

conducts of the leaders, government's

failures in dispensing justice and

its inability to redress genuine grievances

of the people. Inevitably there was

a loss of public faith in the government's

sincerity, if not ability to deliver.

This is notwithstanding our great

legal inheritance!

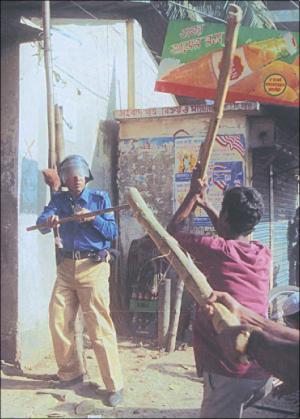

As

a result there is an apparent failure

in our law and order. There is a syndrome

of public defiance to authority and

an apathy to its writs. The manifest

expression of this defiance to authority

abounds all around us and are all

two familiar: the public taking law

in their own hand and the mob dispensing

summary justice to suspected offender,

a blanket flouting of government orders

and so on. And no one knows how many

innocents are perished in the process!

The

public concern over the chaos and

anarchy is obvious. But at the same

time the government is also not unconcerned

and its responses are also apt. The

government has promptly taken step

to arrest the trend. It has beefed

up the law enforcing agencies, introduced

improved crime control gadgets, devices

and, of course also enacted special

legislation to deal with certain categories

of offenders. It's leaders have gone

about exhorting docile people to be

law-abiding. They have poured down

plentiful of pet sermons about their

obligations and the virtues of disciplined

societies. But there seem to have

been few takers. The people, by and

large, remain unimpressed and unconvinced.

The

public concern over the chaos and

anarchy is obvious. But at the same

time the government is also not unconcerned

and its responses are also apt. The

government has promptly taken step

to arrest the trend. It has beefed

up the law enforcing agencies, introduced

improved crime control gadgets, devices

and, of course also enacted special

legislation to deal with certain categories

of offenders. It's leaders have gone

about exhorting docile people to be

law-abiding. They have poured down

plentiful of pet sermons about their

obligations and the virtues of disciplined

societies. But there seem to have

been few takers. The people, by and

large, remain unimpressed and unconvinced.

In

the meantime public defiance stiffens

and social disorder takes much more

diabolical shape. If the government

is perplexed at the development the

people are in no pleasant situation

when choosing between compliance with

grudge and defiance with its accompanying

risks. Those who are ruled find neither

an example to emulate nor an incentive

to comply with the dictates of those

whom they consider out and out hypocrite.

Also the commands of those who rule

ring hollow unless substantiated by

a moral authority.

The

ingredient of good governance which

is essentially the evenhanded implementation

of law and government policy. Such

implementation is possible only if

it is done fairly with the same force

over the privileged as over the poor.

And the onus of this onerous task

lies with the ruler who are customarily

the privileged ones. The standard

application of law for all would involve

some sacrifices on their part by subordinating

themselves to the "due process

of law" even if they are in a

position to evade it. In a country

like Bangladesh this sacrifice is

perhaps the price of a good governance

and rule of law.

The

last but not the least are the factors

of urgency and earnestness -- if we

are to ensure a rule of law in this

country. A time has already arrived

when even decent people have begun

to question: why should they pay taxes

as the proceeds are likely to be embezzled

by their corrupt leaders! why they

should hand over a criminal to the

police who can be easily bribed and

the rogue would be free to resume

his crime with vengeance! why they

should pay back borrowed money to

the Bank -- where another, a bigwig

can manipulate its evasion! It is

precisely the question of restoring

confidence that they do not and can

not happen henceforth.

At

the core of our problems either of

governance or of the application of

law is today precisely the absence

of this moral authority an authority

only with which the Bangabandhu, the

nation's founding father wielded during

the historic non-coperation, power

that had few parallel. Because he

spoke from a moral high ground. In

contemporary political history it

is a unique example of moral authority

at work.

Bangladesh

has a fine legal framework and its

legal inheritances are rich indeed.

Although existing laws are sufficient

to ensure good governance - only if

they are enforced without fear and

favour. But our rulers have a proclivity

to overlegislate, ostensibly to concentrate

more and more power in their hands.

Our failures are not so much in the

making of laws or in their absence

but in implementing them.

Over

the years the government institutions

and the administrative machinery have

gradually lost their capacity to act

upon the laws in a fair, impartial

and effective manner.

The

disrespect for "due process of

law" is what lies at the heart

of the most of the problems relating

to governance. Good governance is

nothing but the obeying of the laws

by every one from the highest to the

lowest in the same standard manner.

When the laws are broken whether for

the good reasons or bad the results

are always adverse. Unfortunately,

breaking of law always begins at the

top because then few can check the

law breaker at that level. One who

breaks law at the top however instantly

loses his moral authority to make

others obey the law. Once the ruler

at the top breaks or circumvent law,

rule or tradition is left with no

authority to stop those under him

from doing so. This is the crux of

the whole problem.

In

our country there are often deviations

and exceptions with regard to the

application of law while making political

favour or dispensing nepotism. That

sets in motion a series of actions

deflecting one from the "due

process of law". In despicable

practice of allotments, permits and

quotas in our political culture one

has to show utter disregard for this

"due process of law." When

the ruler begins to deviate from the

established procedures the permanent

bureaucracy also gets mutilated in

the form of a desperate search on

the part of the rulers for the pliant

subordinates thus compromising the

competence of entire administrative

machinery.

It

is indeed futile to institute a commission

or consultancy or hold seminar or

symposiums to discover where lies

the rot which as in any case fester

inexorably.