Inside

|

Can Our Shipbuilders Make It Alone?

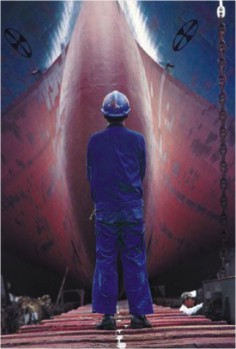

Only time will tell. Bangladesh entered the $400 billion plus a year international shipbuilding market recently. Hats off to the pioneering entrepreneurship of Ananda Shipyard & Slipways Ltd. of Dhaka and Western Marine Shipyard Ltd. of Chittagong. The world of shipbuilding and heavy engineering was once the exclusive domain of highly developed countries, until recently when an unprecedented international trade and shipping boom paved the way for the entry of China and the fresh entry of India, Vietnam, Philippines, and, most recently, Bangladesh. The two yards in Bangladesh are now building specialised ICE class vessels, which means that they will be rubbing shoulders with other world-class shipbuilders in terms of offering a product that will meet the stringent safety and quality requirements of European regulatory authorities. This is by no means a small achievement, considering the fact that export incentives for shipbuilding are non-existent in Bangladesh, and we do not have easy access to steel, the key element in shipbuilding. Taking a cue from these two shipyards, other entrepreneurs/big business houses are currently engaged, or are contemplating to engage themselves, in developing international standard shipyards to join the fray. Reports coming from Chittagong indicate that the ship-breakers there are also mulling the idea of shipbuilding.

The potential of earning considerable foreign currency aside, the shipbuilding industry, if allowed to develop, will generate unprecedented skill development in the heavy engineering fields, whether for a simple technician or an engineer. A ship is made out of thousands of individual elements, and shipbuilding will not only create huge employment opportunities but will also help establish many subsidiary outsourcing/backward linkage engineering industries. The consequent domestic value addition in shipbuilding for export will eventually rise to 45-50 percent from the current 25-30 percent in no time. Imagine the take-home foreign currency amount per year for the government from just 10 shipyards, each contracted to deliver vessels worth $60-80 million. The recent euphoria in the media and the praises by government high-ups are understandable, but, unfortunately, they have already taken the entry of Bangladesh to the world of international shipbuilding and heavy engineering for granted, without realising its magnitude and the pitfalls attached. Because the industry is in its infancy, there are considerable road-blocks to be removed, and that needs the immediate attention of the government. Otherwise, the stakeholders in the country (shipyards and their financing institutions), including the government itself, will soon realise that once the on-going honeymoon period is over, the road to transformation from a ship-breaking to a shipbuilding nation is not as smooth as perceived. Unlike RMG, shipbuilding for export is a highly capital-intensive and high-risk industry for any developing economy, where profit margin usually hovers between 7-10 percent only, and any marginal rollback for whatever reason will eat away the profit completely. Secondly, billions of dollars are at stake here, and international stakeholders such as ship financing banks and institutions, credit guarantors, ship-brokers, ship-owners, fleet managers, and insurers will be at risk if the shipbuilder fails to comply and keep up the commitment for guaranteed quality and strict delivery schedule. Shipbuilders in Bangladesh have yet to gain the required confidence of the international stakeholders in terms of proven capability to build quality ships and deliver on time and are, therefore, looking for additional guarantees which cost more money for our shipbuilders. Bangladeshi banks will have to come to terms with the unknown terminologies and dynamics of international transactions for shipbuilding and ship financing.

Even China, being the second largest shipbuilder of the world after Korea, is under strong pressure from the international shipping community and classification societies to raise the quality of shipbuilding. The boom has seen an unprecedented rise of shipbuilding facilities in China to many hundred shipyards and, according to media reports, 30% of the 160-million-DWT order book at the end of 2007 has been contracted to yards that have yet to build a ship of any sort. It is true that global fleet owners in the last couple of years have been looking at newer destinations like China, India, Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines in order to meet the unprecedented shipping boom driven by increased sea-borne trade, rise in off-shore oil exploration and the ongoing "replacement cycle" of aging vessels worldwide. According to shipping pundits, the shipping boom will, however, smoothen out and stabilise by the year 2016. The galloping Asian economies of China and India combined, emerging economies of Afro-Asia, and the increasing demand for vessels that meet newer regulations in ship construction, will be the key factors in maintaining a relatively steady demand for ships beyond the boom period. The rising labour cost in China, India, and Vietnam (main competitors of Bangladesh for smaller ships) will create an opportunity for Bangladesh to remain competitive beyond 2016, if Bangladesh can gain a foothold now. A modest shipyard in Bangladesh with the capacity to build four 5,000 DWT vessels per year will need a minimum 20 acres of land space and BDT 120-150 crore in capital investment, requiring long term project financing. In Bangladesh, long term project financing is restricted to 5-6 years only by most commercial banks and the current state of two development financing institutions, BSB and BSRS, originally established for long term financing, has made them beyond approach. At the current rate of bank interest (15%) a shipbuilder will have to work for his banker for almost ten years before breaking even -- not a palatable proposition for a promising industry in infancy. Further, the working capital against four such ships with a price tag of $15 million each will require about BDT 200 crore in cash, in addition to bank guarantees and other instruments worth another 100 crore. In case of four similar-sized special purpose vessels such as PSVs or MSVs with a price tag of $25-30 million a piece, the working capital requirement will be as much as 450-500 crore taka, and if one shipbuilder encounters a loss of only 7-10% on account of liquidated demurrage cost alone for shipment delay for whatever reasons, he will be out of business soon. If only five such shipyards are to lose money this way in a given year, the dent in the national economy or our banking system is understandable. The economy could endure the losses of hundreds of RMG factories in its primitive stage (where shipbuilding is standing now), but it will be very difficult indeed for our stakeholders to endure loss of a few shipyards only. Against the backdrop of our overall inexperience in high tech shipbuilding and heavy engineering, lack of easy access to huge capital required and exorbitant lending rates, lack of enough trained workforce in international standard shipbuilding methods and technology, absence of required road infrastructure connecting the shipyards with national highways for heavy load surface transportation, cost of land, and last but not least is our lack of access to cheaper shipbuilding steel and in time, coupled with usual bureaucratic red tapes in acquiring different permits/approvals etc -- shipbuilding will be very vulnerable in Bangladesh in its growing stage. Hence, it comes naturally to one's mind, can our infant shipbuilding industry tread the bumpy road ahead to adulthood alone? Or the pertinent question is: Can Bangladesh grow out of its current infancy with a healthy note to take a bite of the pie (the current shipbuilding boom), and unleash itself for steady progress beyond 2016? Bangladesh can do it, but not without a decisive and unfaltering support from the government for at least the five initial years. The risk is too big for the individual shipbuilders or their financiers to sustain the hiccups associated with our maiden journey into the world of international shipbuilding and heavy engineering. Remember, all of Bangladesh's competitors mentioned here have cheaper and quicker access to their own steel and other components for shipbuilding as well as a heavy dose of government subsidies and other policy supports. The new brand of Bangladeshi shipbuilders enjoy none of the facilities enjoyed by their competitors, except their vision and strong will to succeed, but that will not take them far (one strong wind from the opposite direction will blow away whatever they have achieved so far). The only asset we have is our cheap labour and traditional shipbuilding skill (which definitely needs to be upgraded to the world level now), meaning the shipbuilders of this country would be completely import dependent and will always remain afloat in uncertainty for an indefinite period of time. The only composite heavy steel mill in Chittagong (first of its kind in erstwhile Pakistan) that we inherited disappeared because of our "national inefficiency," so to say, and the consequences are apparent today. Steel for shipbuilding being a bulky and heavy item, the freight cost per ton from China or Ukraine (for example) is almost 15-20% of the actual cost of steel for Bangladeshi shipbuilders. Coming to our technological preparedness, the other most important question is: Are there enough skilled welders, ship fitters, engineers, naval architects, design shops to produce production drawings, yard managers and supervisors with a skill level to take Bangladesh into global competition? The lack of investment and quality work in most of our domestic shipyards has resulted in the migration of qualified welders and ship fitters to the yards of Singapore, Dubai, and elsewhere for the last 20 years. Same with qualified yard engineers and naval architects. Today, the few yards which have gone into international shipbuilding are scrambling for quality manpower, and it will not be surprising if they engage foreign skill in their shipyards. The current boom has also brought in new dimensions in shipbuilding design and engineering to make the ship more efficient in terms of fuel consumption, increasing capacity, more eco-friendly and thereby profitable. Bangladeshi shipbuilders have to raise their standards and capabilities to meet the changing demands of modern day shipbuilding. For example, one team of six shipyard welders in Korea can fabricate over 30 tons of steel per shift/day while the same scenario is 3-4 tons in Bangladesh in our domestic shipyards. The assertion for Bangladesh to remain competitive with cheap labour alone will not sustain unless we develop our technical skill with foreign help or technology transfer, backed by fiscal incentives in its growing stage. The ship buyers from the European Community are emphasising two very crucial factors to remain competitive, one is maintenance of strict delivery time to avoid huge liquidated demurrage cost for delay in shipment running into millions of dollars. Which is only possible to avoid by raising production capacity by investment in equipment and skill development and by reducing the lead time for procurement of production materials from abroad. The other important factor is cost effectiveness, which is possible only when the cost of funds is at par with international lending rates for shipbuilding and government assistance, fiscal and non-fiscal. There is no country on earth including the richest of North America or Europe who have not provided fiscal or other policy support incentives for decades to their shipbuilding industry, which was always considered as the springboard for modern day industrialisation. With the tide of time, the rising labour cost and gradual withdrawal of cash incentives from ships other than for defense and highly specialised vessels in the West have helped the international shipbuilding to gradually shift to the Asian shipyards in the eighties. The smart governments of Asia quietly followed the footsteps of western governments in providing heavy doses of financial subsidies -- as much as up to 60% in Korea -- low cost funds and non-fiscal incentives in the form of duty/tax rebates and low-cost land acquisition to its shipbuilders to generate revenue, employment and skill development in heavy engineering. The decision of Korean government to bail out Daewoo shipbuilding from bankruptcy in the mid-nineties has resulted in Daewoo becoming a trillion-dollar company today. Japan and Korea, armed with their innovative technical skills, (introduction of robots for one), and government incentives slowly emerged as the leading shipbuilding countries of the world in no time. Korea overtook Japan a few years ago, while new players like China, followed by Vietnam, India, Malaysia, and, more recently, Philippines, joined the fray. The classic example of a developing country government's participation in nurturing shipbuilding for export is Vietnam. The recent surge in international shipbuilding in Vietnam was only possible by the planned government support, both financially and logistically. The Vietnam government, in recent years, has pumped in millions of dollars into the country's special shipbuilding zone/area infra-structure development plan and have arranged 400 million euros as grant from EEC in 2004 for an association of about 20 Vietnamese shipyards to transform themselves to international standard by developing modern shipyard infra-structure and by acquiring technical know-how from abroad. From there on, there was no turning back for Vietnam. The Philippines government, following the example of Vietnam, has been successful in developing its shipbuilding capability and even attracted foreign direct investments in this sector from Norway and Korea, with a package of government sponsored incentives. Our neighbour India has taken a master plan to bring India to the level of China in terms of shipbuilding gross tonnage capacity by the year 2015 under a policy initiative taken by the prime minister himself. About 15 new conglomerates have initiated the development of large scale shipbuilding projects in India with an estimated investment of 60,000 crore rupees, and the coastal state governments from Gujarat to West Bengal are luring the investors, offering lands at throw-away prices and other state incentives. The government of India recently formed a consultative committee to determine whether to extend the 30% federal cash subsidy against export which expired recently after five years. According to the Indian shipbuilding experts reported by the media, India will have a cost disadvantage of 30-55 percent compared to China if the ongoing federal subsidy is removed. The state government of Gujarat most recently went one step ahead by announcing it will reimburse stamp duty on land registration for the shipbuilders and providing capital fund with 5% interest subsidy for five years. Pakistani government have sought Chinese government's technical assistance to increase its shipbuilding and ship repair service capacity for very large vessels to earn $60 billion a year. But whether we see any tangible policy formation in Bangladesh for shipbuilding in the offing cannot be said with any certainty. The latest budget, unfortunately, did not press any buzzer for this sector, but this is one sector which cannot be ignored by the government and let its growth potential lie with the aspiring shipbuilders alone. The government has to take a long hard look at the other Asian countries and take note how these governments have helped their shipbuilding industry in their infancy to blossom astronomically within years, creating jobs, revenues, and technical skill which no other sector singularly provided. Government support has always played a key role for nurturing shipbuilding industry the world over even today, and Bangladesh cannot be an exception. To start with, a fact-finding team of highly placed officials and entrepreneurs from Bangladesh may visit Vietnam and China to equip themselves for a serious policy initiative at home. It will not be an exaggeration to say here that, if Bangladesh wants to accelerate and retain her growth rate beyond seven percent in the coming years and become a middle income nation by the year 2016, wholehearted and planned development of our shipbuilding industry could be the "fast lane" to achieve that goal. According to a recent study, shipbuilding has one of the highest economic multiplier effects among all industries, especially in employment and investment, and the technological benefits are outstanding for any developing country. Our government is hereby urged to form a high powered national task force, comprising of the Ministries of Shipping, Communication, Land, Local Government, Labour, Commerce, and Foreign Affairs, headed by the Ministry of Finance & Planning to augment this sector with a two-to-three year "crash program" with the firm intention to create a level playing field for our shipyards in the international market, with pragmatic policy back up for the undermentioned proposals (see box below), or any other viable proposals the government may deem fit. To repeat, government assistance, fiscal and non-fiscal, is a proven formula for success for any shipbuilding country of the world from the dawn of the century. It is possible for Bangladeshi shipbuilders to achieve 2% market share in the small sized ship segment, amounting to $6-7 billion a year, within next five years, but first of all the government has to share the vision of our entrepreneurs to achieve that goal. Our futuristic shipbuilders have done the initiation for a dream start for Bangladesh and now the onus is on the government to strongly ensure that it remains on course, but not with a sleepy start. Otherwise, no matter how gloomy it sounds, the chances are that we may falter. This is the hard reality every stakeholder has to understand today. The current shipping boom has provided a unique opportunity for the entry of Bangladesh in the international arena and we cannot afford to let this opportunity pass by. It is now or never. Mahboob Ahmed is Managing Director, Shipwrights Bangladesh Limited. Lending A Hand -Creation of special fund for equity and/or long term debt financing (minimum 10 years) available for capital investment for export oriented shipbuilding projects and for short term working capital loan, directly from Bangladesh Bank, with lending rates below 8% and/or allow Bangladeshi shipyards to access funds from outside the country particularly for the short term working capital fund against each specific export contract. -Shipbuilding for export being a highly capital intensive industry, government/ SEC may encourage the export oriented shipbuilders to become public enterprises and allow them to go for initial public offering ( IPO) with Greenfield status for raising capital from the public stock and institutional equity market. -Provide minimum 25% export performance grant/export subsidy (for five years) to hedge against the unforeseen in the initial years associated with the exorbitant cost of fund, possible liquidated damage cost, technology import/transfer and extra freight and other cost for importation of heavy shipbuilding materials from the volatile world market, and to remain competitive in its growing stage. This will create an inevitable opportunity for foreign direct investment in shipbuilding, creating a big leap forward in terms of technology transfer and gaining confidence of international stakeholders. -Creation of technology transfer and skill development centres for shipbuilding, initially on the premises of participating shipyards in the crash program, with the financial aid and technical assistance of foreign governments. In this context, EEC/ Denmark/ Norway could be ideal options for seeking funds and expertise. These training centres may eventually culminate into a national shipbuilding training institute. -Creation of 100% free and fast track Green Channel for importation of shipbuilding components against specific export orders without having to provide any bank guarantees which will be unnecessarily very costly and an additional burden for the shipbuilders in terms of the high value of imports in this sector amounting to hundreds of crores of taka and their consequent bank charges and other fees to follow. -Creation of special zones for shipyards with heavy duty roads connecting the major highways for surface transportation of heavy loads or providing the same to the existing yards on a national priority basis. -Adoption of hundred percent zero duty/suppliers' tax/VAT/ AIT facility for import of capital machinery and equipment for export oriented shipyards and backward linkage engineering industries. This facility may be extended to non-exporting shipyards also, for selected items, for building their expertise for domestic shipbuilding. A technologically efficient non-exporting shipyard could become the breeding ground for the development of skill and expertise for the exporting shipyards. -Reimbursement of stamp duty for the lands procured for export oriented shipbuilding industries after making their first export. -Adoption of quicker procedures for allocation of government owned riverside land/foreshores at concessionary prices for shipyard expansion or for new development. -Dredging on demand for shipyard premises requiring adequate water draft during the lean season. -Create a special/separate department/window in the Board of Investment/Export Promotion Bureau to facilitate the investment and development of shipyards with minimum fuss and time, administered by knowledgeable persons/marine professionals. -Government in association with the shipbuilders' association of the country and members of International Association of Classification Societies (IACS) operating in the country may form a quasi-regulatory body and share its administration cost for proactive role in helping to establish strong quality safeguards and systems to support the emerging shipbuilding industry in Bangladesh, to attain confidence of the international stakeholders. It is very important that the sweat of the shipbuilders to build a reputation for Bangladesh cannot be ruined by one bad instance.

|