Inside

|

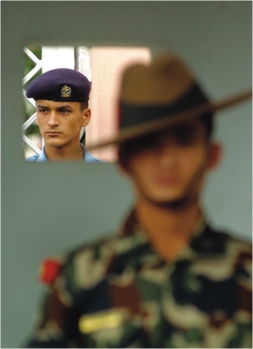

Nepal's Elections: Before and After

Deb Mukharji explores the history behind recent developments in Nepal, and what the future holds for Indo-Nepal relations Close to the stroke of midnight on Wednesday, May 28, the newly- elected Constituent Assembly of Nepal voted 560 to 4 to transform the nation to a Federal Republic. The dynasty founded by the creator of the state of Nepal, Prithvi Narayan Shah, in 1767 came to an end, and his twelfth descendent, Sri Panch Gyanendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev, became a common citizen of Nepal. In these days of instant news and the briefest of attention spans, it is customary to see the recent political developments almost exclusively in terms of the Maobadi insurgency (1996-2006) and its aftermath. Certainly, the insurgency hastened the process of Nepal's political evolution and the Maobadis acted as a most important catalyst. But the aspirations of the people of Nepal go back much further. The struggle against the autocratic Rana regime that ruled over Nepal from 1846 goes back many decades. It was expected that democracy would appear with the regime's end in 1950 -- marking the start of the demand for a Constituent Assembly. This did not materialise, and after a brief period of representative government, King Mahendra downed the shutters on Nepal and created his panchayati raj, inspired perhaps by Ayub's Basic Democracy in Pakistan. Thirty years of sporadic agitation later, the Jana Andolan I in 1990 brought in multi-party democracy. But the negotiated constitution adopted then contained ambiguities that the palace later used to further its autocratic inclinations. Neither did the political parties act responsibly in the years that followed. The Maobadi insurgency started in 1996 after the rejection of their 40-point demands, most of which would have been acceptable to any modern state. The ruthless police action that followed only helped gather greater support for the insurgency, and by the time it ended a decade later, more than 13,000 Nepalis had been killed -- two-thirds by the army. It is a commentary on the curious state of governance in 2001 (and the anomalies of the constitution) that the army was unwilling to take orders from the then elected government without clearance from the palace.

Meanwhile, Gyanendra had succeeded King Birendra after the palace massacre of June 2001. His inherent autocratic inclinations soon came into play. Parliament was dissolved in October 2002 followed by a succession of prime ministers appointed at royal command. Finally, in February 2005, he took personal charge of the state, completing the coup started in 2002. Gyanendra's major miscalculation was his attack on the political parties and direct assumption of power. He had removed the protective shield they provided and thus became personally responsible for all future developments. The avowed objective of overcoming the insurgency was not achieved and almost the entire country outside the major cities came under Maoist control. The political parties, now deprived of the carrots earlier held out by the previous king, reassessed their position. Meanwhile the Maoists, too, had decided in a 2003 plenum that the future lay within the framework of a multi-party democracy. Gyanendra's non-productive coup and his efforts to hold guided elections provided the spark for public agitation. Nepal shut down from the first week of April 2006, in Jana Andolan II. The ruler's partial retreat on April 21, offering only to return to the pre-2005 dispensation, was rejected by the people, and he finally capitulated on April 24 following the army's refusal to fire on fellow Nepalis. Many tortuous negotiations later, Constituent Assembly elections were held on April 10, 2008. The results gave the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) 30% of the votes in a mixture of direct elections and proportional representation, and 38% of the seats. It is highly likely that if the elections had been held entirely on the basis of direct elections, as in the rest of South Asia, the CPN would have clinched a majority of seats. More significantly, the two major parties, the Nepali Congress and the United Marxist Leninist, received serious setbacks and far less votes. Their leadership decimated, conveying the people's desire for change in unambiguous terms. Madhesi parties made a significant entry into multi-party elections. It is necessary to point out that though all political parties had participated in Jana Andolan II, it was essentially a people's movement that spread across Nepal. One recalls the wives of soldiers facing guns, doing their duty, as they said, to their country, as their husbands carried out theirs. The only other South Asian example of a peaceful people's movement removing an autocrat was in Bangladesh in 1990. Nepal's Jana Andolan II is, however, an unique example of people peacefully empowering themselves against the heaviest odds, seeking fundamental changes in governance and the nature of politics. Some major gains have already been made and the path ahead will be strewn with many challenges. But it is unlikely that the old style of politics will be allowed to return.

India has always loomed large in Nepal. The Maoist 40-point demands of 1996 and the more recent election manifesto contain clauses for a review of "unequal" treaties, notably the 1950 Treaty of Peace and Friendship. It needs to be noted that though highlighted by the Maoists, such demands have come from all major political parties in Nepal over the past decades. The 1950 treaty was signed under circumstances that have since changed greatly. The only really functional aspect of the treaty is with regard to the grant of national treatment. Other elements, such as the implied suspicion of China (the treaty was signed only months before the first Chinese occupation of Tibet), are meaningless, given the excellent relations Nepal enjoys with China. India has no preferential treatment with regard to the development of Nepal's natural resources. Nepal imports arms freely, as seen in November 2005, when arms and ammunition were imported from China following an international arms embargo after the royal coup earlier in the year. India has expressed it was willing to consider all options with regard to the 1950 treaty, namely continuation, termination, and re-negotiation. This needs to be followed up by the new government in Kathmandu and the Indian government to remove what has been an unnecessary irritant. That treaty is, however, only one of many arrangements and agreements between Nepal and India. Besides trade and transit, there are agreements on the development of hydel projects, currency, and the employment of Nepali nationals in the Indian army which, in fact, briefly pre-dates India's independence. Several of these agreements have been long criticised in Nepal. A few critical voices are also heard in India. It is best for the future of Indo-Nepal relations if all existing agreements are looked at under the new circumstances in Nepal, so that any rough edges can be smoothed out in the light of mutual interest.

But treaties and agreements do not convey the texture of Indo-Nepal relations. For many decades, those seeking a democratic form of governance in Nepal had often used India as a sanctuary, facilitated by an open border. India provided the space in which the Maobadis and the mainstream political parties could negotiate the landmark agreement charting a route for the future. Also, there are the numerous multi-layered connectivities. The Rana and Shah elite of Nepal often have marital links with former princely states of India. The Madhesis, the people of the Terai, have familial links with Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The Hindus of Nepal venerate shrines in India, as Hindus of India worship at Pashupatinath or Muktinath. Possibly millions of Nepalis find work in India, and some Indians in Nepal. One link that stands severed is the veneration a few Indians felt towards the Hindu king of Nepal, projected as an incarnation of Vishnu. In terms of trade, investment and tourism, India remains Nepal's most significant partner. As Nepal's self-empowered people start their journey into creating an equitable society, and as hitherto muted voices find expression, there will be many challenges and opportunities for both Nepal and India. Strong foundations exist on which it should be possible to build a new edifice of confidence and cooperation based on mutual trust and acknowledgement of mutual interests. Deb Mukharji is former Indian High Commissioner to Bangladesh. |