Inside

|

Bangladesh's Revolution Addiction

Bangladesh is addicted to revolution. It has happened time and again, and despite its uneven achievement record at best, it continues to attract people and individuals who feel that salvation lies in dramatic decisions which ultimately peter out, creating the platform for the next revolution. Many consider the 1971 war as the first revolution, and in the years after independence as the situation crumbled and the suffering of people increased, the call for another revolution began to surface. If the various shades of leftists were calling for one revolution or another, the party in power, the Awami League, and its supporters began to talk of the "second revolution" as the solution to the problems of politics and governance that the country faced. This was, in essence, the populist aspect of Baksal, or one-party rule, as it contained the smell of revolution which till then was the most acceptable symbol of political change. If 1971 was the first revolution, all subsequent "shocks" could also be packaged as "revolution." It was a faith in the description, and perhaps in the process, rather than substance that drove many to believe that as long as it was revolutionary or sudden and dramatic, and even traumatic, things would end in victory. Sheikh Mujib's Second Revolution, Zia's Canal Digging Revolution, and the 1990 People's Revolution Thus, countering the AL has a quasi-ideological aura, whereby any act counter to it is read as legitimate politics by many. This feeling is deeper than admitted by everyone, but can be read in the support for BNP's strength and sustainability as a political force for so long. It is a product of opposition to the Awami League and is made up of a mixed crowd of politicians running from ex-lefties to Islamists. What holds them together is their hostility towards the AL. In some ways, the residue of the second revolution of Sheikh Mujib can be observed more in the BNP in its stubborn refusal to accept the AL than in the AL itself, which has in practice and ideology become largely indistinguishable from the BNP. The Awami League maintains its own "revolutionary" fervour by harkening back to its leadership of the nationalist movement, its role in 1971, claim to undiluted civil political leadership and central sense of destiny that has mingled with its exclusive sense of victimhood experienced in 1975. That has also helped it wipe off some of the stigma it gained for its rule during the same period. BNP itself was a product that could emerge only after AL's departure, and its justification of coming to power lay in ending the "second revolution." Gen. Zia, after coming to power, trashed political revolution as befitting a military politician and said that one should always be careful of "revolution" as it could sweep people away from positions of convenience. It was an honest admission of the anxieties of the ruling class in the mid-70s, the so-called revolutions of the socialist variety had not yet been discredited and were the principal inspiration for social change, including in Bangladesh. Zia opposed that idea and yet had to face up to the fact that people in Bangladesh were enamoured of "revolution" and although all they had were promises instead of deliveries, the fervent heart of muddy Bengal still hankered for that stirring call. Out of this situation emerged the distinctly prosaic revolution known as the "canal digging revolution." The first BNP rule will be remembered for the energy with which this administrative, political, and development agenda was followed, and made into another mandatory "revolutionary" duty of the ruling class. Bureaucrats were mobilised to organise workers and volunteers, and people took to canal digging as the total solution to all that ailed Bangladesh. The long marches of Zia, followed by reluctant bureaucrats and politicians, not used to the physical rigour, were to emphasise the need to be alert and aware, and that in carrying out development work the revolutionary possibilities of a people would be completed. In essence, a bureaucratic imagination of "revolution."

Living with Flops Ershad had come to power promising a jihad against corruption, but as he became too identified with that very process he couldn't prescribe any revolution. Instead, the people opposed to him, including the two ex-"revolutionary" outfits, AL and BNP, planned one. In the end, the long drawn-out agitation culminating in the street struggle produced a situation which could be described as the closest to a "people's revolution." The polemics and cultural by-products of the 1989-90 movement show the confidence and faith of people in dismantling the power base of the ruling class through street agitation and other forms of street revolution. It's also symptomatic of that same belief affecting everyone that sudden dramatic action can change the dismal way of life. This movement, or people's revolution, was bound to fail too because it did nothing to change the ruling class structure, or even the members. Although many were victimised, exposing the harsh undemocratic underbelly of most mass movements, it was a contradiction of politics that was its own assassin. By failing to identify that the revolution could only succeed if the ruling structure was adjusted and governance made accountable, it descended to removing favourites of one regime and replacing them with that of the next. It also legitimised the political process that the opposition had produced, that was based on political rivalry, nepotism, and personal loyalty. The institutionalisation of the neutral caretaker government system was perhaps the best example that while public aspiration had moved forward, the political chariot had not, creating a juggernaut that was unable to roll ahead. In the end, the period often called the democratic phase -- 1990-2007 -- has become the great example of disappointment and lack of meaningful political democracy, not to mention other toxic by-products of such regimes, including corruption and failing state institutions. Our Latest Revolution In some ways, the latest revolution promised the most and its leadership represented the elite class across the board. Unlike Sheikh Mujib's revolution, it was not one of politicians, or like Zia's, which was military in nature, or that of 1990, which was people and manipulated by the politicians. It was a military intervention supported by the civil-military alliance in which various members of the ruling class participated. It could be read as anti-politician, but, given the experience of the past decade, it wasn't an unpopular move. The regime seemed very concerned about the punishment of corrupt elements, which was very popular, and reforming political parties, which was less so. It tried to "reform" political parties and even set up an economic crime confession board, expecting politicians, businessmen, and bureaucrats to declare their crimes and hand over the money. It banned politics for long, while it allowed the emergence of at least two political parties, including one which was birthed as a king's party. It separated the executive from the judiciary, but granting or not granting of bail became a hugely controversial matter and put a large question mark on the senior courts and made the judiciary look amenable to pressure. It did not win any medals as a follower of due process and many of the jail sentences passed were unconvincing to observers and lawyers. It tried to weaken the politicians, but in the end ended up retreating and releasing all the leaders against whom cases and charges were pending, proving that revolution makes leaders forget the realities of the situation that is greater than the strength of the powers that be. The present regime had hinted at an enormous appetite for change, but its lack of success in that pursuit and the stubborn and ultimately successful resistance of politicians has proven that in Bangladesh "revolution" simply doesn't work. This government had seriously bad timing, too, as it came to power when the world was facing huge economic disturbance and Bangladesh was hit by a series of natural disasters including Cyclone Sidr. Global economic turmoil may not have affected the stock market much here, but the squeezed ability of the western buyers is certain to hit the local economy. However, the poorly paid workers have fared much worse than the owners, and their lot has not improved under this regime. This government has not been embarrassed by its lack of connection with the poor. That perspective has been provided by the NGOs which are close to the chief adviser and certainly constitute the most successful segment of the anti-poverty initiative. However, in its drive to reform Bangladesh wholesale, the plight of the poor fell through the cracks of the revolutionary zeal. In the end, it was not much more than an interregnum in Bangladesh's sorry history, and a reminder that in its history of revolutions to change the situation, this was simply another phase. As successful as the previous revolutions, and, one supposes, as all revolutions are destined to be, in the future too.

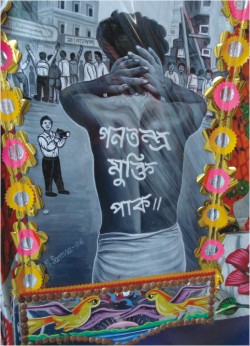

Waiting for the Next, Unfortunately There is a great deal of attraction and power in the idea that some are above history; whether as a person, a group, or an institution, and that the power of the intent is stronger than the clout of reason. Independent Bangladesh has had four revolutions, and in each case the construct coming to power believed in the righteous authority of the convinced, which was itself. No questions were asked by them or anyone else as to whether that dream was real or rational and how it could be tested against the limits and possibilities. It's particularly useful to learn from an adviser of the present regime, who said that the fight against corruption was stalled by bails issued by the courts. In other words, corruption can be fought only if rule of law and rights are suspended. Revolution requires trampling of rights and institutions, though the Soviet experiment is the great teacher that this route simply has never worked in history. He is not talking about the inadequacy of the system. How can we then explain this fatal addiction of Bangladeshi power groups to this "revolutionary" approach against the less than perfect success records of their achievements? Part of that can be traced to the nature of the elite, who have emerged in an environment of unaccountability in society and politics. Our leaders are never questioned or held responsible. People would much rather fall behind a leader and march forward, expecting to be paid for loyalty, than to think of themselves as equals capable of a collective effort. The kind of systems that we have had certainly had a mass-scale damping down of our collective intelligence, and neither our leaders nor the people are ready to examine what keeps going wrong every time. That may also spell out why Bangladesh has reached a point where the governance structure has all but folded and people or individuals no longer think that normal routes of governance can deliver anything, let alone reforms. This is perhaps best demonstrated by the current regime which, after nearly two years of A deeper disease than bribe taking affects us all, and the people who cheer mass arrests and custodial killings are as much victims of the same forces as are their enemies. In the name of revolution, more sins have been committed and more people have lost faith. The continuous cheering perhaps reflects a desperate desire to see things get better, which is never realised. In four decades, we have seen four revolutions and not much progress. The great divide between the ruling class and the ruled, which has taken place over the last four decades, has been the slow and sure revolution that now looks set to be permanent. The business of manufacturing "revolutions" in Bangladesh has become the best way of ensuring the continuation of the same story. Photos: Amirul Rajiv Afsan Chowdhury is an eminent Bangladeshi journalist. |

effort, has beaten a retreat, with the situation seeming to be returning to "normal." It's a victory of the entrenched political forces and displays once more the limits of order, intimidation, security agency intervention, and attacking of the symptoms instead of tackling the system.

effort, has beaten a retreat, with the situation seeming to be returning to "normal." It's a victory of the entrenched political forces and displays once more the limits of order, intimidation, security agency intervention, and attacking of the symptoms instead of tackling the system.