Inside

|

Which Way is the Shore? Rubayat Khan offers a solution for the dire straits of student politics Student politics has always been an issue inviting heated debate and drawing thick lines of division. However, with all the talk going around about student politics following the recently proposed RPO, I feel there has been a frustrating failure in hitting the nail on the head.

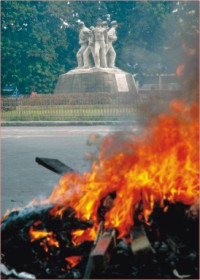

While the government superficially speaks of severing ties between national parties and their student wings, the parties oppose. And in all the beating around the bush, we lose sight of the underlying problems. Therefore, unless the main issues of the debate are placed where they belong and settled once and for all, we will have to be content with how things are at present, without any meaningful change in the situation of student politics on the public university campuses. In this article, I will try to do just that -- to address the subliminal issues that are (deliberately or naively) kept at bay. By analysing the pages of history to deduce some key trends and developments, I will propose changes that might bail us out from yet more years of dysfunctional universities and derailment of students. The Stark Contrast Between Past and Present Whether we consider our language struggle, the 1969 11-point demands, our liberation war, or the re-establishment of democracy in 1991, the cause-driven nature of the student movement (note the word "movement" instead of "politics") was a common thread. Moreover, common students and not just party activists constituted the bulk of these movements, underlining their tendency to surpass ideological boundaries for the greater good. The switch from flashback to present is therefore extremely agonising. The overall landscape of student politics is largely evident in our daily newspapers of the past several years. Armed clashes between the various student factions, killings and rapes on campus, unending strikes and oborodhs, beating up of teachers, extortions and tender-bazi by "student leaders" and destruction of university property are so commonplace that now we now rarely bother reading beyond the headlines. However, media coverage alone is likely to give a very superficial understanding of the true horror of present student politics. For a more first-hand view, I tried talking to some students at Dhaka and Jahangirnagar Universities, the real sufferers of the system, and obtained some paraphrased accounts: And what happens to the remaining majority who live outside the halls? In my discussions with some non-resident students who live with their families or in student messes around the DU campus, they complained about the ills of current party politics within their campus -- the constant risk of injury and death, the session jams, about their helplessness in changing the fate of their friends who are everyday sufferers, and so on. Being largely outside the grip of exploitation, but suffering directly and indirectly nonetheless, they develop apathy, and in some cases, aversion, to this student partisanism (I will use this word throughout the rest of this article to distinguish it from the cause-driven student politics of the past). As if all this is not depressing enough, the teachers and university office-bearers in this "Age of Empire" are hardly the referees and mentors they are expected to be! Factionalisation of the faculty and administration into all shades of colors (shada-neel-golapi, etc) has stripped them off the moral high ground which they previously had to command respect and obedience from their students. In fact, according to most teachers, students and experts I interviewed, and research conducted by Prof. Arild Ruud of the University of Oslo, student partisanism has direct "vertical linkages" with teacher politics, all the way up to the vice chancellor's office. Due to the strategic importance of campus control, parties consider dominance over campuses "as half the electoral battle won." Therefore, universities nowadays are essentially just another battleground for power. Every regime change sets of a chain reaction - the vice chancellor is appointed politically, who then appoints provosts from under his wings to control the halls, and they in turn serve their party by allowing their own student faction to control and abuse hall-allotments and admissions. What meaningful change from those old days when the provosts were academic luminaries bound only by their own morals and standards! A Chance Outcome or Calculated Plot? Perhaps the first turning point in the history of student politics was when in 1976, the Political Parties Regulation Act for the first time kept provision for political parties to "include any organ, associated or front organisation of the abovementioned organisation, such as students, labour …" (Article 2(d)). It was this subtle change that ultimately allowed the inclusion of utterly unacceptable and undemocratic clauses such as Article 13 in the BNP constitution, which states that "the chairman can take punitive action or cancel membership […] of any worker or leader of a support organisation [including Jubo Dol] for disobeying rules, anti-party activities or other unacceptable behaviour." Awami League is hardly better, although their approach is less dictatorial -- Article 25(1) of their constitution allows their Central Coordination Committee to determine the rules of their affiliates (including Jubo League and Chhatro League), and requires these affiliates to "remain liable" for their actions to the Central Committee. Even in the past there were ideological affiliations between national and student parties. But with the institutionalisation of political control on student parties, the first nail in the coffin of student politics was hammered. In early 1990s, another major blow to student politics was the fall of socialism, the ideology that historically attracted students the most, causing a disorienting ideological vacuum. While the Dol and the League were already devoid of any form of ideology, Islamic groups such as Shibir used this opportunity to establish their strong foothold in many universities, presenting an alternative ideology to the students. And as is always the case with religious politics, it succeeded in strongly polarising the student community. Around this same time, the rapid economic changes that were taking place (i.e. high government expenditure in infrastructure, increasing inflow of remittances, etc.) generated a capital-rich business environment that, in the absence of sound regulatory institutions, needed armed musclemen to protect its interests, secure tenders, and so on. By this time, student politics was already flooded with weapons, thanks to armed conflicts between pro- and anti-Ershad factions. Therefore, this derailed section of the student community became the first generation of armed "student leader" cadres. When the flag-bearers of democracy(!), BNP and AL, came to power, they were already protectors of these new businesses, and indeed, many of their parliamentarians were businessmen themselves. Over time, they realised that this strategy of spoiling students was not only good for business, but also for politics. As long as students could be kept divided and engrossed in money and power, there would no longer be strong-fisted ideological challenges to their flawed policies and corrupt politics. Therefore, they tightened their grip over their student factions, as mentioned earlier, by installing sycophantic non-students into leadership positions, and this transformed loose ideological affiliations of student parties into gross subservience. One source of challenge that was anticipated, and indeed emerged, came from the student unions, including the most powerful, DUCSU. Therefore, the most legitimate voice of the students also had to be neutralised. It is a sad irony that as soon as democracy was instituted in the country, the democracy in our universities was snatched away. DUCSU elections (along with RUCSU and CUKSU) have not been held for the last 17 years, since 1990! A testimony to the success of all these plots was the 1996 demonstrations that led to the fall of the Khaleda government, which was led by government officials, not students. It is not highly surprising that such frustrating developments would cause student masses to become disenchanted with politics, i.e. become de-politicised. Owing to the bitterness of being dominated and abused and exploited by a small "political" minority who wielded all the power, the masses turned apolitical, apathetic, and self-centered. What has catalysed this process even further is the rapid corporatisation and consumer culture that has flooded Bangladesh over the last decade or so. Nowadays, many of the youth I meet are incapable of dreaming "big" -- the only aspirations their hearts are capable of conjuring a 9-5 clerical job at a multi-national company, or at best, a prosperous life abroad. In short, even though unpredictable events and circumstances partially contributed, evidence suggests that the degradation of student politics and the concurrent de-politicisation of a large section of youth are hardly random phenomenon. Over the past two decades, the youth have been systematically drained of their dreams, castrated of their capabilities, and divided into factions to serve the interests of certain sections of the society. That a long-past-prime generation devoid of values and ideologies is still ruling Bangladesh is largely a function of making impotent the young generation. A section of our youth has been intoxicated with drugs and weapons and raw power, and that section is used to destroy the inherent revolutionary and political spirit of the rest. What is the Solution? More recently, the interim government has probably comprehended that, and suggested instead that the links between national parties and student factions must be severed. This, while aiming in the right direction, is an imprecise and incomplete remedy. And the entire approach of suggesting randomly concocted solutions off the top of one's head is not likely to go down well with the universities, and of course, the political parties. Inevitably, teachers and politicians have protested, and as of now, it seems this particular requirement for party registration might be scrapped off the final RPO. In my interviews, one thing that was encouraging was that every single entity, including UGC members, emphasised the need for students to gather around causes and ideologies, and once again become the nation's vanguards. Everybody agreed that we must preserve the right of students to dissent -- dissent for their cause, for the cause of the people, and for the country; that what must be stopped is the "dissent" (read "violence") by non-students, for the interests of their national patrons, against the interests of students. Bearing that common vision in mind, therefore, let us try and identify the means to a better future for student politics.

Break the Chief Mechanism of Control Over Student Parties Reinstate Democracy Within Student Politics Also, any ordinances or acts that address public universities and student activism therein, e.g. the currently stuck UGC proposal on Public Universities Ordinance 2007, must clearly state the activities student can undertake, along with those they cannot. Currently, the statement in article 49(5) of the abovementioned ordinance, the only article that mentions student politics is extremely vague and can easily be abused to stampede genuine student movements and protests for legitimate causes. Such a clause must explicitly mention that students can organise themselves ideologically in student parties, free from political interference, that these parties must acquire legitimate power through the student union elections, and must refrain from violence (killings, extortion, vandalism, etc.). They must also mention that non-violent protests like michil, sit-ins, and hunger strikes will be allowed. If democracy is reinstated in the universities as outlined above, eventually, student unions in the major universities can, like in neighbouring India, and indeed Bangladesh of the past, become ultimate testing and breeding grounds for future leaders of the country, and practice grounds for democratic thought and governance. Address the Broader Issue of Education Policy and University Governance Therefore, the overall academic, legal and political framework within which universities operate is to be addressed. The UGC, in its proposal on Public Universities Ordinance 2007 to the government, has suggested a new system for appointing vice chancellors and deans (Article 10(1) and 27(5)), and that teachers be disallowed from being active members of political parties (Article 56(2)).

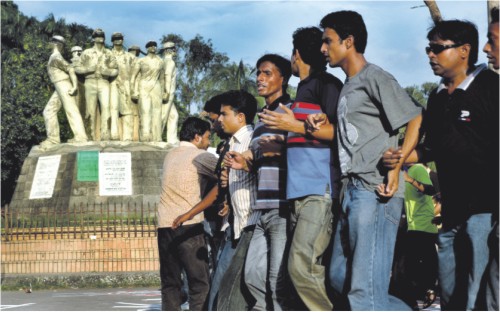

While these might bear fruit, such ideas should be generated through a transparent procedure, perhaps using a national education committee consisting of prominent educationalists, for greater acceptability. Within a broader educational policy framework, this committee must come up with specific and practical mechanisms for self-governance of universities, meritocracy in faculty/ administration appointments, and eliminating room for political manipulation in student union elections. And this time, to avoid the fates of eight previous education committees whose recommendations have been discarded and ignored, the government should declare a mandate to implement ex-ante. Eliminate Fear, Injustice and Intimidation Depoliticising the administration and faculty will also play a crucial part in ensuring justice for students. If the hall provosts are appointed according to their merit, and held accountable to their task of distributing seats to the most deserving candidates, illegal allotments can be stopped. Further laws must protect students from getting forcefully evacuated from their halls without reason. The universities must also enforce strict rules to expel anyone possessing illegal weapons on campus. A Call for Action Progress is not being made because the debate is happening between the caretaker government and the political parties, not where the issue truly belongs: within the student community. It is time that those ordinary students who have thus far quietly suffered come out, unite and raise their voices against this utterly dysfunctional system. Reforms will only happen when the demands for it will come from within, vigorously and persuasively. It is not as if students have never protested this system. However, these movements have Nevertheless, the lesson to be learned from the 2002 movement and the long list of others that have happened before and since is that ordinary students not belonging to any political party can unite and strongly challenge the status quo. And that is what is once again necessary. Leadership and organisation of this movement must come from all individuals and groups from various corners of the student community who are disenchanted and marginalised by the system -- the left groups, the cultural associations, the study circles, and so on. Indeed, they are the only entities that still have a degree of acceptability within the general student community (this is evident in the fact that most post-91 student movements -- including the nineties movements against rapists in Jahangirnagar, the July 2002 movement, the 2003 movement protesting the attack on Prof. Humayun Azad, the 2006 movements on Fulbari and Kansat, etc.) have spontaneously organised themselves under leadership of these groups and actively kept out the mainstream entities like Chhatro Dol and Chhatro League. If we look back at our history of student politics, the most glorious phases have been those where students have treaded over ideological boundaries and united under a common cause. The time has come again when the youth must unite to stop their destiny from being determined by ill-willed conspiracies. Let us unite again to finally make student politics "of the students, for the students, and by the students." "Today, I beat up some students in my hall. I would never do it under normal circumstances, but I knew I had to in order to keep my leaders happy and my place in the hostel secured." "I had an exam. Suddenly, a party 'bhai' came and asked me to join a party michil. I had to miss my class and follow instructions. I would have to give up my dignity if I declined. I had been degraded publicly for not following orders before.” "My friend's father sells vegetables in a small town outside Dhaka. He sold nearly all his assets trying to sustain his son in university. But his son, in the no-win game of securing his hall seat, had to join party politics and nearly destroyed his academic standing. He got beaten up several times, and even worse, was falsely indicted in a murder case recently." "We, some ordinary students, were protesting the accident of a student in campus, demanding safe roads. An order came from 'above' to turn this into an agenda to topple the government. Suddenly, we saw party affiliates come in from all sides and smashing buses and windows. Police came in and beat us up and put us in jail. Nothing happened to the party people they fled. Amidst the chaos, our issue was lost. We lost.” Photos: Amirul Rajiv Rubayat Khan is a founding member of Jagoree, a platform for non-partisan political engagement of youth. Visit blog.jagoree.org or email at rubayat.khan@gmail.com.

|

tended to be catalysed by and masked under other causes, like the July 2002 anti-administration movement following a police raid of Shamsunnahar Hall, and died down when the primary demands were met. While July 2002 was an inspiring saga of ordinary students rising up to protest gross injustice, and ultimately succeeding to oust the VC, most of the seven-point demands, including restructuring of university regulations to eliminate hall-occupation and armed terrorists on campus, never reached fruition.

tended to be catalysed by and masked under other causes, like the July 2002 anti-administration movement following a police raid of Shamsunnahar Hall, and died down when the primary demands were met. While July 2002 was an inspiring saga of ordinary students rising up to protest gross injustice, and ultimately succeeding to oust the VC, most of the seven-point demands, including restructuring of university regulations to eliminate hall-occupation and armed terrorists on campus, never reached fruition.