Inside

|

Entity Zeeshan Khan traces the origins of the Bengali Muslim nation In 1342, the kingdom of Shatgaon, ruled by Shamsuddin Iliyas Shah, annexed the two other Muslim kingdoms of medieval Bengal -- Lakhnauti (Lokkhonaboti) and Shonargaon -- almost immediately after all three declared independence from the Sultanate of Delhi. This enlarged kingdom, the Sultanate of Bangala, endured as an independent country for over 230 years, with its capital in Pandua, and later in Gaur, half of which falls within the territory of present day Bangladesh. In some senses, the Sultanate of Bangala can be considered a prototype for the Republic of Bangladesh, since much of what we have inherited as our cultural and political legacy comes from this era, with parallels that include the name of the country, the name of the currency (tanka), our religious leanings, our current language and literature, many folk and spiritual traditions, and a rough approximation of territorial delineations.

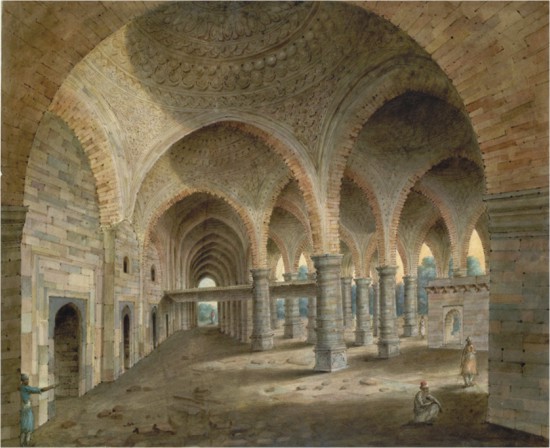

It would not be erroneous to say that the political identity of Bengal as we know it, first as an independent Sultanate, then successively as a Mughal, British and Pakistan province, and finally as a Republic, has its genesis in this period. The Iliyas Shah dynasty was, however, a foreign dynasty, hailing from Sijistan in Iran, and, despite the fact that it had asserted its independence and established a strong and self-assured kingdom (building the Adina mosque in Pandua, at the time the largest mosque in south Asia), it remained an alien presence in the delta. Whether the largely Hindu/ Buddhist and Bengali-speaking population viewed their Persian-speaking Muslim rulers as occupiers cannot be known for certain; however, what is known is that, since as early as the time of Ghiyasuddin Shah, the grandson of Shamsuddin Iliyas Shah, the dynasty's rule was being undermined by Raja Ganesh, an influential Hindu landlord with roots in the deposed Sena aristocracy -- an aristocracy which reigned before the arrival of Bakhtiar Khilji in 1206 (or 1204). Ganesh successfully captured the state and was de facto ruler of Bengal between 1410 and 1415. To be fair, it should also be mentioned that the dynasty had already begun unraveling, with sons killing fathers for the throne. Ostensibly, the rebellion was a reaction to the foreign nature of the administration, but realistically it was about control. Religious prejudices must have also played a significant part, as Raja Ganesh, upon seizing power, proceeded to persecute the Sufis of Pandua. Bangala had already become home to numerous saints of the Chisti order, who, as was the custom of the time, enjoyed a close relationship with the king through a system of mutual patronage. A ruler's legitimacy came from the moral endorsement implicit in his closeness to a respected saint. Conversely, the absence of patronage meant that the moral health of a reign could not be assured. Raja Ganesh was not afforded such patronage nor did he seek it, setting off alarm bells throughout the kingdom. Nur Qutb-i-Alam, the foremost Sufi of Pandua, was particularly disturbed by the takeover and went as far as inviting the Muslim king of neighbouring Jaunpur to invade Bengal and overthrow the despotic Ganesh. The king of Jaunpur accepted the invitation and amassed overwhelming force on Bangala's borders, shifting the balance of power. Expression The offer was originally made to Ganesh himself, which he (impressively) declined. It should also be mentioned that Raja Ganesh was notoriously ruthless and unpopular, even among the Hindus, whom he claimed to represent, and his departure was welcomed with a certain degree of relief from all quarters. With this, the Sufi executed a brilliant move in hard diplomacy and goes down in history as the saviour of an Islamicate identity in Bangala, which is now to be governed by an indigenous king -- establishing the precedence that neither ethnicity nor lineage was any longer of consequence. Jadu, now Jalaluddin Muhammed Shah, ruled, and, just as it was embodied in his person, infused Islam with Bengali culture. This fusion extended into the architecture of his realm and triggered the development of Bangla as a parallel court language. He was the very first Bengali Muslim king ever to exist, and was an exceptionally good one. His rule started off a process that will see Islam in the delta uncoupled from Persio-Arabic culture and linked, inextricably, with Bengal and its culture. The significance of this cannot be overstated in relation to the present character of Bangladesh. The ending of the Iliyas Shah dynasty and the appointment of Jalaluddin Shah is significant for a number of reasons. First, because it resulted in the indigenisation of the Sultanate, and second, because it demonstrated the Sultanate's ability to outlive the dynasty that established it. It had become an entity in itself, and would continue to exist as such despite several changes in leadership. For all intents and purposes, a state had emerged, and a nation -- a Bengali Muslim one -- was following close on its heels. The Iliyas Shah family returned to power after Jalaluddin's son's reign, but surprisingly, did not reverse the policies of its predecessors; rather, they continued to expand the indigenisation process. The descendents of the Iranian Shah were now perfectly comfortable accommodating themselves into the new culture of this new state.

The state reached its pinnacle in Gaur (where the capital of Bangala was shifted to during the rule of Jalaluddin Shah) under another ruling family -- the Hussein Shah dynasty. Following a series of coups and counter-coups by Abyssinian military officers, Allauddin Hussein, a Meccan Arab and vizir of the last Abyssinian general came to power in 1493, putting an end to six years of martial law. This began the most enlightened period of medieval Bengal, which has since become known as the Golden Age -- and for many good reasons. It was in this period that we see the patronage and subsequent proliferation of Bengali language and literature throughout the Sultanate, as well as the abolition of the jizya (non-Muslim tax) and the appointment of non-Muslims to high ranks within the administration. It was also a time of territorial expansion and an unprecedented era of peace and prosperity, allowing Bangala to flourish both culturally and spiritually. Essence Mutual curiosity between the religious orders in Bangala had existed since at least the 12th century, when the Amrtakunda, a Sanskrit manual on tantric yoga was translated into Persian and Arabic in Lakhnauti and circulated as far as Kashmir under the title of Bahr-al-hayat. The Sufis of the time, hoping to understand transcendent reality and recognising Bengal as a mystical place of the occult, sought to incorporate the esoteric practices and philosophies of local yogis into their own religious lives. Similarly, Hindu mysticism, after coming in contact with an Islamic world-view, began redefining itself according to the Sufi worship of God-Love. Beneath both these newer layers remained a Buddhist perspective, which had dominated Bengali spirituality for over a thousand years prior to the arrival of the Sens. The confluence of these three traditions, encouraged by Sri Chaitanya, resulted in a spiritual practice reliant on devotional singing (kirtan) and chanting as a means to both profess and transmit the love of God, manifested, in this case, as Krishna. The parallel with Sufi practices such as qawaali and zikr, is unmistakably clear. What makes it even clearer is the fact that Gaur Vaishnavism, as this new cult came to be called, registered itself as a monotheistic religion and disregarded the traditionally Hindu distinctions of caste -- moves that were revolutionary at the time and were undoubtedly influenced by Islam's presence in the delta. Naturally, this created friction with the Hindu Orthodoxy, but was received favourably by the court in Gaur and by the Sufis. Recognising Chaitanya's philosophy as a kindred one, Hussain Shah offerred him protection and allowed him to preach and propagate his new religion, resulting in the gradual accommodation of Vaishnavism within Bengali Hinduism. It is possible that with its conceptual similarities to Sufism as well as its emphasis on casteless equality, this movement laid the foundation for the proliferation of Islamic teaching throughout the delta, as it would have taken only a small theological hop to go from Vaishnavism to Islam, but this cannot be empirically confirmed. The Vaishnavas will later join forces with the Sufis themselves to spawn the Baul tradition, an integral component of Bangladeshi culture and arguably the most relevant vehicle for spiritual enrichment in the country. Conclusion Hussain Shah's first son and successor, Nusrat Shah, viewed the rising power of Farid Khan (Sher Shah Suri) in Bihar as a welcome buffer between Bangala and the Mughals, and fostered friendly relations with leaders of the Pashtun influx. His brother, however, was less astute and his hostility towards Sher Shah led to the latter's sacking of Gaur in 1537, bringing an end to the Sultanate's isolation. Bengal became Sher Shah's launching pad for his conquest of north India, which expelled the Mughal Humayun from Delhi altogether. Humayun later reconquered Delhi and parts of north-west India, but Bengal remained outside the Mughal sphere and in the hands of Afghan kings -- first the descendents of Sher Shah and then the Karrani dynasty -- until 1576 and the emergence of Emperor Akbar.

After years of fierce resistance by the remnants of Pashtun power and the twelve Bhuiyans, which saw the famous Rajput general Man Singh himself deployed to the region (establishing a garrison town that would later become the city of Dhaka), Akbar's rule in Bengal was finally consolidated in the early 1600s, ending 233 years of political and cultural independence. Its new provincial status became immediately apparent with the introduction of Mughal architecture, Persian and then Urdu into the delta, and with the re-establishment of a social hierarchy determined along foreign and local lines. Tragically, Bengal's own Muslim culture would be side-lined by Mughal chauvinism, and that unique syncretism achieved by the Sultans of Bengal over a course of two centuries seems almost destined to be relegated to history. However, miraculously it isn't, and despite being a province for almost 400 years, an independent state reappeared on the scene in 1971, bringing with it a new commitment to the land and its people, to its language and culture, to a Bengali school of mysticism and to the development of its own distinctive world view. Zeeshan Khan is a communications officer for the British government.

|

Bangala had become a Bengali kingdom, signaling the self-confidence and endurance of Bengal's ancient civilisation, as well as Islam's ability to embed itself among the people it reaches. To put it simply, Islam became Bengali, and Bengal became Muslim.

Bangala had become a Bengali kingdom, signaling the self-confidence and endurance of Bengal's ancient civilisation, as well as Islam's ability to embed itself among the people it reaches. To put it simply, Islam became Bengali, and Bengal became Muslim.