Inside

|

Holding the Guilty Accountable Mizanur Rahman Khan calls on the courts to protect the environment

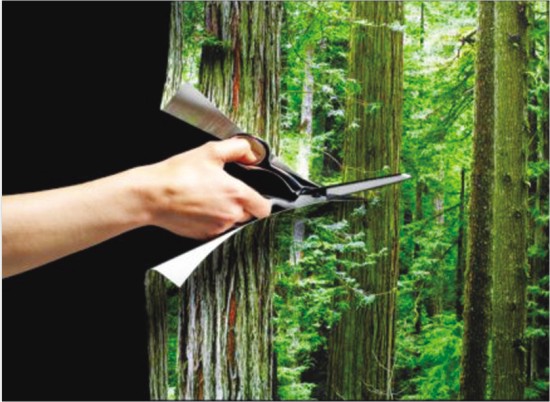

The momentous directive given by the High Court Division (HCD) on June 25 to save four ecologically threatened rivers has encouraged me to reflect seriously about the Public Trust Doctrine. The directive sends a clear message to the defiant businessmen who are still unscrupulously engaged in their grubby trick of filling up the rivers for their narrow selfish gains at the expense of the common public good. They must be resisted fully and forcefully. The HCD bench led by Mr. Justice A.B.M. Khairul Haque has directed the government authorities to "remove all garbage and illegal structures from the rivers by November 30, 2010." The HCD has renewed its directions after eight years to relocate the deadly tanneries by February next. The industries minister, after the failure in the past 23 years to relocate the tanneries, has expressed his inability to cope with the deadline. The minister's remarks about ''at least 18 months'' implied that it might not come into reality even after the 18 months. An article that appeared on June 20 in The Daily Star said: "A survey conducted by the DoE in the recent past identified 1,176 industrial units as the biggest polluters. It reveals that 14,000 tonnes of solid waste and 16,000 cubic metres of chemical waste are discharged by those industries every year into the rivers of Dhaka." Considering the ''reckless pollution'' caused by the 903 or 1,176 industrial units, Mr. Justice A.B.M. Khairul Haque in his July 15, 2001, verdict said: "The sorry state of affairs cannot continue unabated." But, admittedly, it is continued, in the words of Justice Haque: ''Not due to any lack of legislation rather, due to unresponsiveness of the concerned government officials.''

The Supreme Court of India, in 1988, directed closure of the tanneries which had failed to take minimum steps required for the primary treatment of industrial effluents. To protect the Ganga near Kanpur from uncaring discharge of waste matter, the Indian Supreme Court stood unequivocally for a tough stand: ''We are conscious that closure of tanneries may bring unemployment and loss of revenue, but life, health and ecology have greater importance to the people.'' Unfortunately, we do not have a history of affirmative public interest environmental litigation (PIEL) activism. That explains why our ecological verdicts are not numerous. We got an act in 1995 and its effective enforcement only commenced in 2006. That explains the existing sorry state of inadequate legal activism to protect our ecology and the environment. To promote positive and affirmative jurisdiction, the constitutional courts are sometimes looking for broader public support base in absence of the manifest lack of positive commitment of the executive and legislative branches. Public awareness needs to play a most potent role in due protection of our ecology and environment. The Supreme Courts in other parts of the world are now progressively relying more upon a UN-supported Polluter Pays Principle (PPP). It is still foreign to our higher courts. The PPP suggests that "the polluter should internalise all the environmental costs of their activities so that these are fully reflected in the costs of the goods and services they provide." Besides, the user pays principle (UPP) applies "the PPP more broadly so that the cost of a resource to a user includes all the environmental costs associated with its extraction, transformation and use (including the costs of alternative or future uses inevitable)." Almost 22,000 cubic metres of toxic liquid waste is discharged by the tanneries every day into the Buriganga. Around 10,000 people died of various diseases caused by pollution. "The cost of waste disposal into the water is yet to be determined," confirmed the newly appointed chief of DoE, while talking to me on July 2. Our law did not codify the PPP explicitly but the remedial measures for injury to the ecosystem were inserted in Section 7 of the 1995 Act in 2000. It says: "The DG of the DoE may determine the compensation and direct the person to pay the same or, in appropriate cases, to take corrective measures, or do both, and the person so directed shall be bound to comply with the direction.'' No one has yet been brought to book, except some sound polluters. About 550 industries contribute to more than 60 percent of the poisons that pour into the rivers. The 2001 HCD verdict reflects our dismal environmental state, saying: "We found to our dismay that the precautionary principles embodied in the act were not properly implemented, as they ought to have been." Judging the development of the last eight years, it is not an exaggeration to say that its dismay has turned into a nightmare. The polluters and encroachers of the river Bias of India, the Hudson of New York and the famous Thames of London faced exemplary punishment by the superior courts of the respective countries. Now the polluters and encroachers of the rivers Buriganga, Shitalakhya, Turag and Balu deserve to face the same stern fate, if not more, from our higher courts.

Indeed, in a contempt case relating to environment litigation, the HCD imposed a fine of Tk.6 lakhs for non-compliance of its order. But the money was never realised, the case is still pending before the Appellate Division. The Supreme Court of India had recognised the PPP long ago. They held that: "PPP means that absolute liability of harm to the environment extends not only to compensate the victims of pollution, but also to the cost of restoring environment degradation. Remediation of damaged environment is part of the process of sustainable development." The Gas Guzzler Tax in the US is indeed an eco-tax based on the PPP. Actually, it reflects the motto of Plato: "If anyone intentionally spoils the water of another ... let him not only pay for the damages, but also purify the stream or cistern which contains the water." Dr. Jona Razzaque of the University of the West of England wrote in her 2004 book titled Public Interest Litigation in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh "Unlike Bangladesh and Pakistan, the judiciary in India applied this principle vigorously. The Indian court applied absolute liability for the polluters to pay up the cost of pollution and the cleaning up cost. In Pakistan and Bangladesh, there is, unfortunately, no application of this principle.'' In an e-mail response on June 9, Khorshed Alam, senior lecturer of the University of Southern Queensland, Australia, who obtained his doctoral degree on the Buriganga, while supporting the PPP said: "We have to bear in mind a few issues. First, many of the entrepreneurs (small and medium) along the Buriganga river are enjoying their comparative advantages in production due to their free-license to pollute the environment. If they are required to pay for the pollution, they will lose their competitiveness and won't be able to survive. So, when you introduce such a drastic policy (PPP), you have to invest (public and private funds) on innovation and technological improvement to remain competitive in the market place.'' It is true. But there are a good number of large-scale industries which could easily be identified as river-grabbers and polluters. They should be dealt with not only unsympathetically but also sternly and most harshly. Apart from the government and environmental courts, the judges of the Supreme Court are at liberty to impose exemplary punishment for river encroachment by invoking the public trust doctrine, and to invoke the PPP for the perilous pollution. Indeed, I agree with Dr. Khorshed Alam when he writes: "There are sources of pollution which are not identifiable. We call them non-point sources of pollution. Studies have shown that market-based policies such as incentives are more viable in addressing this compared to command-and-control approaches such as PPP. Therefore, we need a combination of both -- PPP and tradable permits.'' Unfortunately, the constitution of Bangladesh, like India, Pakistan and Nepal, has no specific provision about the environment. Even the word environment is not specifically referred to in our constitution. Due to this, one may argue that our constitutional courts may be reluctant to impose exemplary fine under the public trust doctrine and invoke the PPP. The public trust doctrine is based on the Justinian Code, the collections of laws developed under the auspices of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I from AD 529 to 565. It states: ''By natural law, these things are common property of all air, running water, the sea, and with it the shores of the sea. The state of the government cannot do harm by selling them to any person.''

This doctrine can gap the constitutional or legal vacuum, if any. Whenever any breach of those principles occurs, the Supreme Court, as the guardian of the constitution, and hence protector of the common public good, can wield its potent jurisdiction to protect our fragile nature and environment. It is time that Bangladesh courts enforce dynamic exercises of the public trust doctrine. If we effectively contain the encroachers, the polluters and the worst offenders, then it will be tremendously useful in controlling the sources of pollution. It is assumed that illegal structures are the principal forms of pollution. The Supreme Court of India invoked this doctrine in 2002 and imposed a fine of Rs.10 lakhs on Mr. Kamal Nath, an influential Congress leader who is the current Union cabinet minister of road transport and highways of India. He was given land for building a motel near the bank of the Bias, a Himachal Pradesh river. To protect the motel from flood, he built a structure that disrupted the natural flow of the Bias. Following a PIEL, the SC has awarded Rs.10 lakh as an exemplary compensation. It was the cost for restoration of ecology, considering that the offence was a tort committed against the community. The motel was also fined for pollution under the PPP. The state government was also held to have committed "patent breach of public trust by leasing out the land." The Indian SC aptly rejected the plea that it could not lay down special damages avoiding the jurisdiction of environmental courts. The SC of India declared the doctrine as a part of the law of the land in 2000. They affirmed the PPP was a rule of customary international law in 1996. Our SC cannot be a silent onlooker, while the PPP is sleeping in the lap of the DoE and the environmental courts. The US giant General Electrics (GE), is now supervising and paying for healing of the $750 million Hudson program. This is a unique case of the PPP. An estimated 1.3 million pounds of hazardous chemicals will be transported from Hudson to a Texas treatment site. Do we need a law like the US Refuse Act of 1899 ("nothing could be dumped into a river except storm drainage and water") to be supervised under an independent environment body like the ACC? Interestingly, the 1899 US act provided for up to half the fine to be paid to those who had provided the information about the source of pollution. The US court fined GE $200,000 in 1973, which was an exemplary punishment. This verdict had given a tremendous boost to the Save Hudson movement. The UK Environment Agency prosecuted a total of 266 companies in 2003, resulting in total fines of more than £2.2million for environmental crimes that include river pollution. Thames Water, Britain's largest water company, has been fined £125,000 for polluting the River Wandle in what the court described as "a 5km tragedy" for the water course. In 2000, Thames, Water again was fined $400,000, the largest fine ever under the waste management law. It is high time for our superior courts to invoke all these doctrines judiciously, and to punish the alleged offenders who are indeed committing a crime against humanity by destroying the river, the waterways and water bodies. Experiences show that the mere directives by the Supreme Court could not check the 'defiant businessman' who is desperate to grab the river -- as displayed in June 26 front page of The Daily Star.

The Environment Court is empowered to convert the fines imposed by it as compensation to be paid to persons affected as a result of the commission of an offence under the law. But the lower court is reluctant to exercises this jurisdiction. Even the victims cannot file a suit in the courts below without obtaining the sanction from the DoE. This must be revoked now. I humbly suggest establishing an exclusive green Bench in the Supreme Court, since the number of HC judges has recently been increased. It is a crying need to establish strict liability in environmental cases and resort to suo moto actions. Bangladesh now needs consciousness and hence effective vigilance to protect our ecology and environment. Mizanur Rahman Khan is Associate Editor, Prothom Alo.

|

We are all living in an unfortunate world where, despite the force of higher law courts, the politics of impunity is gaining driving force. Most of the times, the eviction of illegal structures is halted on the popular plea of employment.

We are all living in an unfortunate world where, despite the force of higher law courts, the politics of impunity is gaining driving force. Most of the times, the eviction of illegal structures is halted on the popular plea of employment.