Inside

|

Madiba Moments Nausher Rahman searches for the man behind the myth As a name, a face and a legacy that needs no introduction, Nelson Mandela is perhaps the most recognisable figure on the planet today. On July 18, 2009, as he marked 91 years of life, the world turned to him and paid tribute to the last of the giants amongst us. On television, radio and newspapers, the universal respect and love he engenders poured forth in a rare display of unanimity in our constantly uncertain times. It is not without reason that we will all salute him. Inestimably across his own country, and indeed across the world, our humanity is immeasurably better off for his life and lifetime. His famous long walk to freedom was a path he travelled for all of us, to the loss of his family, health, freedom, safety, and, perhaps worst of all, his youth. His best years he gave to us. Living in South Africa, it is difficult to explain how much he is a part of our individual and collective consciousness. Madiba -- as he is affectionately known, in deference to his clan name -- radiates his magic upon all. Everyone has a Madiba moment -- when they saw him walk out of prison free at long last, when they cheered amongst the throngs as his motorcade drove by, when he donned the Springbok rugby jersey (a symbol of the old dispensation) to inspire victory at the World Cup, when they heard his exhortation to a country on the brink of an uncivil war that the time for peace had come: "Throw your guns in the river!" Like a tata (grandfather) equally adored by many grandchildren, we each have a special connection with him.

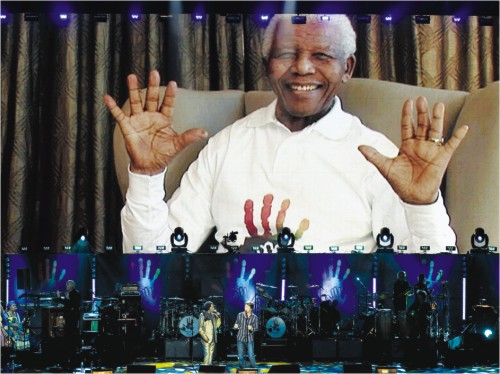

Here he is immortalised in every way possible. Roads, bridges, and entire municipalities are named after him. In plaques and statues, on stage and screen, in songs, books, and poems, his legacy is rejoiced in all eleven official languages. For black and white South Africa to be in agreement -- still no easy feat in this country -- is mark enough of his inspiration. My own introduction to South Africa was sitting in Dhaka, in 1994. I have faint memories of watching the news as an impressionable 14 year old as the BBC broadcast Winnie Mandela casting her vote for the first time in a free South Africa. My young imagination certainly did not understand the gravity of those pictures, as apartheid's ramparts finally buckled under the weight of each hard-earned ballot. A few years later, also in Dhaka, thumbing through an edition of Time magazine, I came across Madiba's most famous words. The shudder I felt at reading the words then was as real as that I feel now simply remembering them. Speaking from the dock at the Rivonia Trial in 1964, staring unflinchingly at the death penalty, he declared: "During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if need be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die." With the understatement typical of a teenager, I promptly pinned the words to the wall beside my desk. Come early 2002 I found myself nervously staring at the prospect of going to South Africa to study. The farthest end of the Dark Continent beckoned, and my first anxious steps into Africa were met with the electric and eclectic energy of Johannesburg. The drive from the airport took me through the suburb of Houghton, home to Mandela (when in the city) said my beaming chaperone. Hardly a day would go by without a news item about Madiba. Visiting leaders of the world would serenade him, dignitaries would jostle for that prized picture beside him and celebrities would fawn at his feet. All the while, he would maintain his dignified composure, even as the weight of the passing days slowed his walk and little by little stooped his shoulders. His grace would shine through the pictures in his special smile, his particular warmth impossible to disguise. As all others before me, I was hopelessly smitten and wanted badly to see him in person. The near misses were many -- by chance arriving at a shopping centre to find the breathless people saying he had just been there; the announcement of his first 46664 Aids benefit concert in Cape Town -- an extravagance ill afforded by a student's lifestyle; most public appearances booked out in moments while others open to the "invitation only" class. The closest it would seem I would get would be the occasional encounter with a Mandela grandchild on the social circuit. As the world of working life unfolded, the routine of living slowly replaced the restlessness of younger days, and slowly the hopes of my own Madiba moment faded. Then, in an unexpected bolt from the blue, in early 2006 came a chance to meet with his ex-wife, Winnie. She was by now carrying the double-barrelled surname Madikizela-Mandela, an uneasy union of her maiden name with his (though to many still best described as the firebrand revolutionary Comrade Nomzamo). My enthusiasm at the chance to meet this colourful and controversial icon was only accentuated by the thought that this was the one person who perhaps knew him better than all. As it would turn out, my naive plans of asking her questions about him were beguiled by her own considerable charisma, as I found myself mesmerised in the attendance of her memorable (and palpable) personality. A trip to the Mandela Family Museum in Soweto's famed Vilakazi Street later that year provided a revealing insight into his days of infamy, when still a saboteur and loathed enemy of the state. His old house, shared with Winnie and their children -- and still in its original state -- provided truth to the thought of eminence needing not grandiose beginnings. It was a week since Prof. Yunus's acknowledgement by the Nobel Foundation's Peace Price, and in a twist of fate that night I spent in a bed and breakfast a few houses down from Madiba's old one. Fated, I say, because Vilakazi Street was famously once home to two recipients of the same Peace Prize -- Archbishop Desmond Tutu and of course Mandela himself. Perhaps that would be the extent of my Madiba moment, entwined with Bangladesh's own Nobel laureate? Then suddenly, last year, came the long-awaited unveiling of the 46664 Johannesburg concert. Prisoner number 466 of the year 1964 had donated his old prison number as the identity of his new fight against the scourge of Aids, and was trying to raise awareness through a series of high-profile concerts. The big question remained as to whether Prisoner Number 466/64 would be there himself -- 89 years old at the time, his public appearances were now intermittent and marked by a slow frail walk and the inevitable marks of time. Undeterred and unwilling to miss the opportunity, we booked tickets well in advance and on December 1, arrived at the Ellis Park stadium well enough in advance to ensure a spot as close as possible to the man himself on stage, should he appear. As the concert slowly unfolded, predictably the highlights were the strains of protest songs of years gone by -- none better than Peter Gabriel's plaintive ode to the fallen father of Black Consciousness, Steve Biko. The crowd, impatient in the late afternoon sun, was a restive body of energy awaiting the appearance of Madiba. Yet with each cry of his anguished chorus the crowd quietened, till seemingly captured by the haunting memory of Biko's brutal felling. As one act replaced another, eventually the stage gave way to the perennial crowd pleaser, the white Zulu, Johnny Clegg, performing with the Soweto Gospel Choir. After a few typical high-energy songs, Clegg launched into his most famous protest tune, Asimbonanga (Mandela). Plaintive in its emotion, the song is one of the most original political songs penned, and speaks to the time when Mandela was in prison and banned by the apartheid government.

Clegg's song -- itself once banned by the government -- asks why we have not seen him for so long, and leaves unspoken the question of what he looked like then, when the song was originally recorded. It is a lingering and unforgettable melody, at once joyous and sad, mournful yet wistfully hopeful. Repeating over and over the last refrains of the chorus, the choir was captivating: Asimbonanga Then, for a moment, Clegg looked lost on stage. Walking uncertainly, he seemed to be mouthing the words with his mind elsewhere. The moment he stole a quick look to the side of the stage, the crowd sensed what was afoot and the buzz of anticipation rippled across the stadium. A moment later, with a brisk walk, came a man onstage carrying a distinctive lectern. Immediately the voices rose as everyone scanned the scene in front excitedly. Then some movement to the side of the stage, as a shuffle of bodyguards and minders could be made out. And then, slowly and suddenly at once, we saw him! Beautiful white hair, an unsteady and slow walk, body bent between a cane and his wife's shoulder, and the familiar if weary face. The ecstatic screams of the crowd filled the air as a crack of energy pulsated through us all. Young and old, male and female, black and white, everyone started jostling for a better glimpse. Screams of ecstasy started filling the air, as to my left and right tears streamed down the frenzied faces of grown men and women. The distinct shiver I felt down my trembling back knew we were beholding greatness, quivering fans in front of the world's biggest star. Impossibly the multitude of cries got louder and louder, a disharmony of almost evangelical hysteria. As he slowly drew near the lectern, imperceptibly a section of the crowd slowly changes its screams to a growing chant of "Maadeeba, Maadeeba." He was now at the lectern, smiling and serenely looking on the screaming, chanting, joyous thousands. Suddenly I felt the enormity of it all. Here I was standing 25 feet away from him, an unbroken view of this great man. He stood smiling, allowing us our indulgence. Then slowly the stage behind him started turning to reveal all the performers of the night lined up behind him, their heads bowed with respectful restraint. We signalled our pleasure at the sheer showmanship of it all, and, he slowly lifted his hand to give a wave. Our shrieks redoubled -- he waved! Some moments later his hand came up again, this time softly signalling for silence. To a man, everyone suddenly stopped, transfixed and not daring to interrupt him. All I could hear around me were soft sobs as people slowly wiped their eyes. And then he spoke, voice still proud and strong. His calm confidence seemed to fill the stadium and envelope us all. To a man, we were spellbound at the effortless natural authority of this ninety year old man. A week ago, I was fortunate enough to have been invited to the 7th Annual Nelson Mandela Lecture in Johannesburg by the gracious offices of our own Prof. Yunus. Sitting a few feet away from the stage, I watched again as Madiba slow shuffle turned a hall full of political luminaries into mere fans -- adolescents amongst greatness. Prof. Yunus' lecture was touching, intelligent and inspiring -- yet my experience was all about my second Madiba moment.

He certainly does not have many birthdays left, and more than anyone else he deserves his time alone and with his family. We cannot give him any gifts more valuable than heeding his call for a just and universal humanity. Eventually there will be no one left to say they saw him talk, and he will be gently laid down in the pages of history books. Even then, those remaining will still surely speak of him with the same marvel that marks our tones today. Long after he has returned to the earth of Africa, we will remember him on his birthday. Certainly till the end of my days, when I see the tributes every July, I will smile in the magic of my Madiba moment. The wall beside my desk in Johannesburg now sports a new pinup -- the only picture I took that night at Ellis Park to have escaped my trembling excited hands unscathed and distinct. It shows him leaning on the lectern, behind him a phalanx of celebrities with heads bowed to the biggest star of them all. Happy birthday tata Madiba. Ngiyabonga for my Madiba Moment, and most of all, siyabonga for your long walk. Nausher Rahman lives in Johannesburg where he runs Grid Digital, a digital media and marketing company.

|

The ban carried an injunction against any pictures of Mandela being published anywhere in South Africa, and remained in place for some 30 years. Thus the curious situation before he walked out of prison when the whole world cried his name and cause, yet none knew what he looked like -- the last picture of him available was three decades old. In his autobiography, Mandela narrates the story of being taken around Cape Town in secret when in covert negotiations with the government. He writes of sitting in public looking around to see if he was recognised -- but realises the frightening effect of the effort to erase every trace of him from public consciousness.

The ban carried an injunction against any pictures of Mandela being published anywhere in South Africa, and remained in place for some 30 years. Thus the curious situation before he walked out of prison when the whole world cried his name and cause, yet none knew what he looked like -- the last picture of him available was three decades old. In his autobiography, Mandela narrates the story of being taken around Cape Town in secret when in covert negotiations with the government. He writes of sitting in public looking around to see if he was recognised -- but realises the frightening effect of the effort to erase every trace of him from public consciousness.