Inside

|

Who are We? Jyoti Rahman ponders imagined nations and a real republic The first general election in what is now Bangladesh took place in 1937. About 10 per cent of the adult population voted for the legislative assembly of the British Indian province of Bengal. Elections were held under communal electorates. The Indian National Congress became the largest party, but fell well short of a majority. More importantly, it performed very poorly among the Muslim majority of the province. Muslim seats in the assembly were divided between A.K. Fazlul Huq's Krishak Praja Party, H.S. Suhrawardy's Muslim League, and independents, with Huq's party winning the most seats. Huq was committed to secularism or pluralism and expressed an interest in forming a coalition government with the Congress, which also claimed to be a secular party. Provincial leaders of the Congress were keen on the idea, but it was vetoed by their all-Indian leadership. Huq formed a coalition with the League -- an overtly communal party. Within three years, he would be moving the Lahore Resolution. Within a decade, Bengal would be partitioned. What if the Congress had taken up Huq's offer? Perhaps a pluralist government in Calcutta would have proved that Hindus and Muslims can co-exist peacefully? Or perhaps communal tensions would have doomed any such government from the beginning? Perhaps we would have seen an independent Bangladesh of some form much earlier than 1971? Perhaps a Bengal-wide revolutionary movement would have emerged? Historical "what ifs" are fun parlour games that have no right answer. Instead of imagining what might have been, it is more instructive to think about how we have imagined our national identities over the past few generations. Note the plurals here -- Bangladeshi / Bengali Muslim / Muslim / Pakistani / Bengali / Bangal / Ghoti / Indian / Hindu -- it's not always clear where one ended and other started. And seldom have we even bothered to remember the marginalised communities who might not want to identify with any of these labels. And note the word "imagined." As Benedict Anderson described in his seminal work, a nation is "an imagined political community" that its members -- people of the nation -- imagine themselves to be part of. That is, all nations, and nationalisms, are stuff of imagination necessitated by political exigencies. Ours have been no exception. All successful politicians in our history appealed to one or more of those above-mentioned identities at some point in their career. Most of our intellectuals and thinkers, artists and writers, filmmakers and poets have paid homage to one or more of these labels. Even when our opinion-makers imbibed some internationalist ideology like Marxism or political Islam, their expressions were rooted in one of these local, tribal, identities. And so we have come to imagine Bangladesh in exclusivist terms, where some people have a privileged position and others need to integrate, whether it is stated explicitly or assumed implicitly. Thus, some imagine Bangladesh to be the national homeland of the Bengali Muslim nation to which all non-Bengali Muslims should integrate. Others imagine Bangladesh as the national homeland of the Bengali nation. Therefore, not only should non?Bengalis integrate into the Bengali identity, Bengalis outside Bangladesh should also pledge allegiance to it. Yet for others Bangladesh is the national homeland of eastern Bengalis, who are different from western Bengalis, independent of their religion, and non-eastern Bengalis should integrate … one gets the picture.

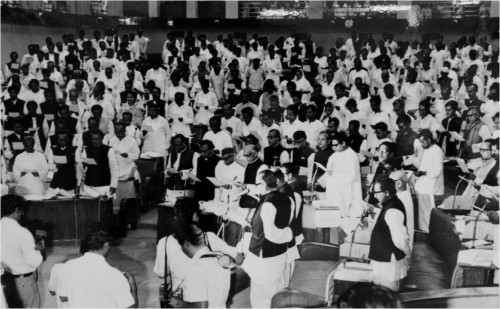

Let's add to the "what if" mentioned at the beginning of this piece. What if Jinnah had said that Bangla would be one of the state languages of Pakistan? What if Ayub Khan had a heart attack in 1955? What if Pakistan had won the 1965 war against India? What if Sheikh Mujib made a deal with the Pakistani generals? How many other what ifs can we think of? How many answers can we give to each question? How long is a piece of string? We can spend a lot of time imagining historical "what ifs." But if we analysed our history without nationalist imaginations ("imaginationalism"?), we would see that Bangladesh is a product of complex set of historical developments, none of which was in any sense inevitable. Our borders are what Lord Radcliffe left us with. We became independent at the time and manner we did because of a set of (mis)calculations by key players. Things could very easily have been different. Nothing about our existence as a sovereign state was historical inevitability. All that said, history has given us this territory that we call the People's Republic of Bangladesh. Can we imagine a history that is reasonably true to what actually happened over the past century and does not rely on some form of tribalism and exclusivist notions for Bangladesh? It turns out that at least two such histories exist. One narrative goes like this. Bangladesh was born out of a revolutionary war that sought to create a classless exploitation-less society. That revolutionary war was waged by ordinary soldiers, university students, industrial workers, and peasants. It happened after a revolutionary uprising in 1969. And Bangladesh is heir to a tradition of uprisings going back to the 19th century if not earlier. This narrative has many polemicists. But there is another narrative: Bangladesh came into existence because of the conscious decisions of the people of this land to create a political order where governments are accountable to those governed, and an economic order that gives everyone equal opportunity. Unfortunately, very few people tell this story. And yet, this story is probably more in line with what has happened in Bangladesh over the past century than any other stories going around. When people of this country wanted to end the zamindari system, when they protested the imposition of Urdu, when they demanded that their taxes and export earnings not pay for someone else's war over a distant hill, when they opposed religious fanaticism, they probably did so for political democracy and economic opportunity. To support this contention, let's look up two memoirs. One of them is by someone who witnessed the political changes of this land first hand from very close quarters, someone whose family members are among the famous and powerful in today's Bangladesh. Another one is of a relative nobody who has spent his entire life in the mofussil. But both Abul Mansur Ahmed's Amar Dekha Rajniti'r 50 Bochor (50 Years of Politics as I Saw It) and Jatin Sarkar's Pakistaner Jonmo Mrittu Dorshon (Witnessing the Life and Death of Pakistan) argue that the political evolution of the British Bengal to Bangladesh was about representative government and economic freedom. This is not to say that tribalism in the form of this or that nationalism wasn't present. But both authors consciously choose representative democracy over tribal identities and nationalisms. That's why the first post-liberation government's Bengali chauvinism reminded Ahmed of successive Pakistani government's use of Islam. That's why Sarkar noted wryly that people who in 1970 screamed about a thousand year old Bengali nation were more often than not the same ones who waxed lyrical about the glories of Islamic civilisation a few years earlier. If these memoirs don't suffice, let's think about the most successful politician in our history. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman won as clear a mandate as one can get in politics. What was the mandate for? Certainly not for a radical restructuring of the society. And without denying its role, it wasn't an unambiguous mandate for nationalism. What the mandate was most clearly for, what was at the core of Mujib's platform, was a message of equality of opportunity for the people of this land, of economic freedom for the masses. And how did he receive this mandate? Not through an armed revolution, but through the ballot box.

And yet, our democracy has never really been in a particularly healthy shape. After many fits and starts, our democracy still involves electing a parliament that chooses a prime minister who has unbridled executive power for five years. We still don't have an effective local government. Parliamentary oversights need not be enforced. If the prime minister's party has absolute majority in the Parliament (which has been the case under all four elected governments), the opposition can still be ignored altogether. The ruling party can pass any law as they see fit, appoint anyone to any post as they see fit, distribute relief materials as they see fit, give out procurement tenders as they see fit -- they can control everything from Bangabhaban to the local cricket club for five years as they see fit. The prime minister and whoever has her ears (or whomever she delegates her powers to) can behave like dictators. Meanwhile, the opposition party has nothing to do for five years. Shut out of the political system altogether, they have every reason to be obscurantist and no reason to cooperate with the government. Is it any surprise then that our democracy is imperilled time and again?

Our leaders and thinkers have spent a lot of time and effort imagining the nation. In comparison, how much have we thought about what our republic should be like? History has bequeathed us with a state, and it is up to us -- the generation born and raised in this People's Republic -- to shape this land. Where is the effort to do so? A friend once told me that she sang at the Speaker's Corner in London's Hyde Park. When I asked what she sang, she replied: Why, Amar Shonar Bangla! Of course, she'd sing that, what else would it be? Those of us born in free Bangladesh tend to identify instinctively with Amar Shonar Bangla -- along with the green-and-red and shapla -- irrespective of differences in religion, class, or political opinion. While we feel our Bangladeshi identity, seldom do we think what it means to be a Bangladeshi, and there is little clear articulation of what kind of a state our People's Republic should be. After all these years, the most famous speech in our history is still Sheikh Mujib's defiance looking down the barrel of Pakistani guns. We are still waiting for the speech that sets out a vision for our Republic. But why do we need a speech from a hero? Isn't it up to us to discuss, debate, and define our People's Republic? And the good news is, we don't have to imagine a liberal democratic narrative for this Republic. It is the most truthful account of our history. Jyoti Rahman is a blogger and can be reached at jyoti.rahman@ drishtipat.org. |

The commitment to the supremacy of the ballot box as the mean to change government has been one constant feature of our political culture. We have tried to imagine different nationalisms over the decades. We have debated socialism, or the role of Islam, in our polity. But we held firm to the conviction that democracy is the best form of governance. That's why even Sheikh Mujib failed with his "second revolution." That's why military rulers eventually came around to electoral politics.

The commitment to the supremacy of the ballot box as the mean to change government has been one constant feature of our political culture. We have tried to imagine different nationalisms over the decades. We have debated socialism, or the role of Islam, in our polity. But we held firm to the conviction that democracy is the best form of governance. That's why even Sheikh Mujib failed with his "second revolution." That's why military rulers eventually came around to electoral politics.