Inside

|

Of Elusive Freedoms

Indian television news is designed for a privileged few, says SOMNATH BATABYAL.

Before mid-2007, not many in India would have heard of Nandigram. A rural area, about 70 kilometres south-west of Kolkata in West Bengal, Nandigram entered the national consciousness in an orgy of violence that shamed and shocked the ruling Left Front state government. On its orders, the police had been attempting to expropriate 10,000 acres of land for development from the local villagers who opposed the land reclamation violently. Clashes with the police that still continue today, left hundreds dead on both sides; the numbers inflating or deflating, depending on who tells the story.

Yet, a year previously, when the plan for land acquisition was first publicly mooted, not many would have had an inkling of the trouble to come. The state's media had, including private news channels and newspapers, backed the plan whereby the Salim Group, an Indonesia based company would acquire land in the state to build a petro chemical hub. The government termed the area a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) and the media hyped the narrative of soon to come economic prosperity.

On the morning of June 14, 2006 when a senior employee of the company arrived in Kolkata from Jakarta he was therefore, enthusiastically greeted by the press. The visit became the most talked about story on news channels across the state. On Star Ananda, the first and most prominent of the 24-hour Bengali news channels in West Bengal, the story dominated the headlines. Throughout the day, there were stories of major investments about to be made by the Indonesian company and how this was to be a new chapter for the economic prosperity of a state which had, under a Left Government for more than three decades, failed to attract significant foreign investment. The tide, if the reports were to be believed, was turning.

The stories of this coming prosperity were punctuated by live reportage of the movements of the Salim group official. Journalists reported on his meetings with bureaucrats and ministers; the camera tracked his every move during the inspection of the earmarked land in Nandigram, documenting his interactions with the local villagers. Virtually deifying the man, television screens were flooded with images of him being garlanded by the very villagers whose land was about to be taken away. A journalist reporting from the area where the land acquisition was proposed, responding to a query from the news anchor said that there were no protests from farmers who were giving their land away happily, realising it was for their own prosperity and progress.

However, subsequent events made it clear that the journalist had been somewhat selective in what he had chosen to report. The villagers refused to give up their lands, the government had to backtrack on their plans and reality refused to bow before its media articulation.

|

ANTON OVCHARENKO/GETTY IMAGES |

What is press freedom? For me, the issue boils down to one fundamental question -- who is writing/broadcasting and for whom? In state controlled media houses of the erstwhile Soviet Union and to a certain extent say in present day China, the issue is simple. The press is not seen to be free because the state decrees what can be talked about and what shall not enter the public domain. In our free democracies, in Bangladesh and in India, we cry foul against government interference in our media and are proud that we have a thriving, supposedly devoid of interference, press. Let us pause here for a moment and examine a few facts.

If we look at the Nandigram episode above and how it was represented initially by the news media and contrast it with the events on the ground a few months later, we have to confront the question, was the journalist covering Nandigram lying? How could a person miss so much animosity, the seething anger of thousands of peasants about to be dispossessed from their lands, farmers and their families who will kill and be killed in trying to protect the source of their livelihood? The answer to this question is not a simple yes or a no but an exploration of the query, I hope, will reveal much of the complexities and realities of the television news media in India and its neighbouring countries.

For a country obsessed with big numbers -- largest democracy, oldest civilisation, double digit growth rates in economy and in population -- here is a startlingly small one: there are only 7,000 television viewing households in India. Households which matter, that is. You might have heard other numbers. We are a country where there are more than 75 million families that have cable connections. Or that 100 million own television sets in this almost super power nation. And yet television news is produced only for 7,000 households.

Around the astounding smallness of this number, amongst the incomprehensibly big ones, lie a conspiracy; and the crux to the question, who produces news and for whom? The conspiracy exists between private networks, multinationals and the most bandied acronym in media circles, TRP or Television Rating Points. It results in news being produced by the rich for the well to do and the conversation is reduced to the three C's: cricket, crime and cinema and as a senior Indian television journalist put it, crap being the fourth.

It is a truism today to say that since the 2000s the growth of the Indian television industry, especially news, has been exponential. From just one news channel in 1998, today India has close to 60 24-hour news channels spread across the country. News anchors are the new Indian celebrities, articulating reality to India's millions. With citizen journalism, live outdoor broadcast vans fitted with the latest technology, talk shows and discussions, analyses and reports, there seems no end to the goodies for a nation of viewers until very recently served only state propaganda as news. One must wonder why then, with over 60 odd television news channels on air, we get either a Saans, Bahu aur Saazish or Saans, Bahu aur Sansaar as choice when we switch news channels, programmes based on soap opera stars and their shenanigans? The reason is, as I claimed before that Indian television news is increasingly a conversation between a privileged few. The rest of the country is there to be ignored or marginalised. I explain this politics of forgetting in six easy steps.

One. Unlike say the BBC or Channel Four in the UK, which we regularly use as flag posts for good television content, private television channels run on advertising money. Consumers, you and me, do not pay for news costs. No, the meagre amounts you dole out to your cable wallah does not run television news. In fact, at most times the money does not even reach the television industry and the cable mafias in both India and Bangladesh are a menace. But that is another story for another time. As corporations subsidise news, they want to understand audience behaviour to justify their spending.

Two. This is where rating agencies step in. From the 1920s, when the commercialisation of radios in the United States started, rating companies have analysed audience behaviour and given feedback to advertisers to help them plan media strategies. However flawed, this for now is the only quantifiable methodology that seems available.

Three. Advertisers are looking for consumers to buy their products and consequently they are interested in the well to do, affluent who can afford to spend money. A poor person might watch television but they are of no interest to the advertiser and consequently kept out of the rating process. A very high percentage of audience monitoring boxes -- there are 7,000 of them in India -- are therefore placed in richer neighbourhoods of metro cities. Sporadically moved around, the audience base remains constant. Till recently, poorer states like Orissa or Bihar were left out of the purview, as were all of the North-East and Kashmir. Nandigram and its villagers do not constitute our television viewing world.

The company director of one of India's biggest television companies explained to me "The whole country could be watching but if those 7,000, rich households don't, then my ratings are zero. This means advertising revenues will not come my way. We target only those 7,000."

Four. How do you target an exclusive audience?

The human resources manager of another national news channel explains "Since the audience is elite, I have to keep their concerns in mind, what they want to hear about, what they want to know. I figured that if journalists come from the same circle as the audience, they would be better able to attend to their wants and needs. I now make sure that my journalists belong to the party circles in big cities."

Five. So in comes the privileged classes of our societies -- young men and women who do not understand what happens when bus prices rise for they have never travelled in one, people who have never stood in queues, negotiated the summer streets -- articulating our world to us. Look at the happy, made up faces. This India not only shines, it positively glitters.

|

RICHARD HANDWERK/GETTY IMAGES |

You might be wondering if I am not being overly reductive?

Six. Besides spending 10 years as a journalist, I spent two long years asking reporters how they understand what makes news, what is news sense? The answer, with minor variations, always was: "News sense is understanding what the audience likes. When I think of the audience, I think of what my wife/husband would like, what my friends are interested in and I have the answer to what is news." So there you go. Recruit the rich, ask them to produce what their families like and you have news content for the vast Indian sub-continent. If you make errors of judgement, your audience do not mind. Like in Nandigram, where a middle class reporter was articulating his desire to see major foreign investments come into the cash strapped state. He was wrong but his middle class audience, desiring the same things, clapped along.

Nandigram is certainly not the first case where media myths have been contradicted by later events. In the general elections of 2004, with the incumbent ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), riding the crest of media adulation, a sweeping victory was predicted. The BJP had wooed the media with a story of economic success and technological revolution, coining the phrase "India Shining" as their election slogan. Media and its middle class consumers bought the story. The majority of the voting public in India who live below the poverty line, for whom television news is as remote as three square meals a day, did not. The party was severely trounced. Prominent journalist M J Akbar articulated the media's collective embarrassment when he remarked that 'we all have egg on our faces'.

Despite the media's attempts, reality does not always give into a comfortable middle class discourse. India, behind the façade of skyscrapers and flyovers, its multi-millionaire industry tycoons, its jet setting film stars and celebrated technological geniuses, is a country where most of the population live in unimaginable squalor. To millions, clean drinking water remains a mirage. High child death rate, female infanticide, droughts and famines might not occupy prime time news television discourse but they lurk in the peripheral, threatening to embarrass a carefully constructed articulation of an emboldened nation by its affluent citizens. The violence in Nandigram, which still sporadically continues today despite the government abandoning the land takeover plans, show that when news production fails to be interrogative and critical, and when the needs and interests of people are ignored or trampled on, the seeds for serious civil or economic disruption can be sown.

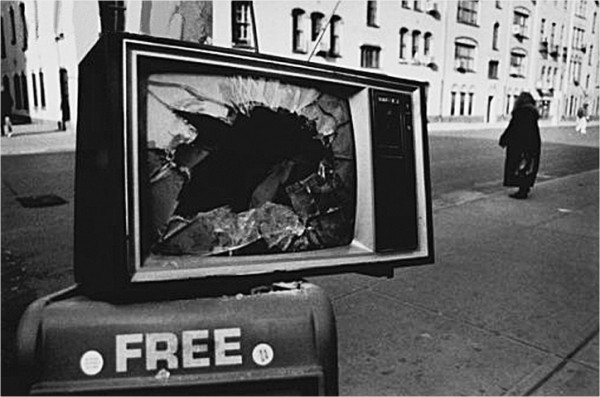

For now, however, enjoy the news. They mean to entertain you. Just don't believe that the press is free.

Somnath Batabyal is Fellow at the University of Heidelberg.