Inside

|

The Power of Television

JYOTI RAHMAN contemplates the good, bad and the inevitable of television.

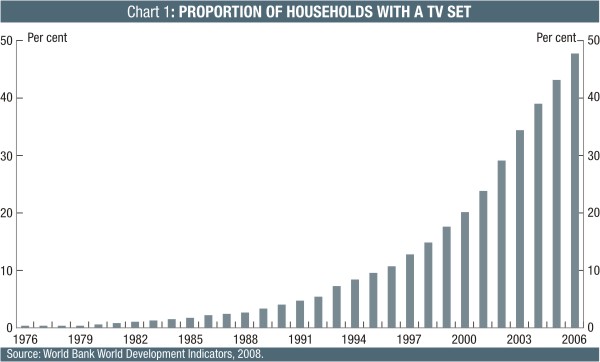

On December 25, 1964, a handful of people in the then Dacca witnessed the birth of something new in our part of the world -- television. It began with daily four-hour black and white programmes. Colour programmes started in December 1980. Until the early 1990s, the only channel on air was the state-run Bangladesh Television, though from the late 1980s, people started watching Indian channels. Cable television arrived in 1992. Ekushey TV, a private telestrial channel, revolutionised programme standards in the late 1990s. In the past decade, over a dozen private satellite channels have sprung up. By 2006, nearly half the households in Bangladesh had a television set, compared with less than 0.2% in 1975 (Chart 1).

This piece celebrates television in Bangladesh by discussing the role TV has played in shaping our culture, how commercial TV can act as an agent for positive social change and the interaction between TV, politics and business.

About a decade ago, writing about the way globalisation (and its regional manifestation -- Indianisation) was affecting our culture, Prof Zafar Iqbal noted two ways we could respond to it. One was that of the Taliban -- smash the TV sets and reject everything that is deemed 'unauthentic'. He suggested an alternative way, using Bangla rock bands as an example.

What he might have had in mind is the fact that Feedback's Melaye Jairey has become a staple of Pohela Boishakh celebrations around the country (and indeed the world, for Bangla culture is no longer limited to its historical geographical confines). What he might have had in mind is possibly the role artists like Habib or Anusheh Anadil have played in reviving folk songs, albeit with 21st century twists.

Sure there are controversies about the relative merits of specific developments -- for example, not everyone likes the peculiar dialect Mostafa Sarwar Farooqi uses in his shows. But can anyone deny that, from the pioneering works of Fazle Lohani, Abdullah Abu Sayeed, Shafiq Rehman to today's dozen plus channels, television has played a significant role in our cultural (r)evolution? Even a decade ago, Bollywood ditties dominated most wedding celebrations in Dhaka. Could the Monpura soundtrack or Mila edge Bollywood out without television?

Of course, there is a huge subjective element to culture. Whether one likes a particular dialect or type of music is essentially a matter of personal choice. However, there are other aspects of culture that one can make objective statements about. Cultures that treat women with dignity and respect are usually also of societies with better standards of living, measured in objective criteria such as life expectancy or infant mortality.

And according to Robert Jensen of Brown University and Emily Oster of Chicago University, television improves women's status in a major way.1 Their research explores the effect of the introduction of cable television on gender attitudes in rural India during 2001-03. They find that access to cable television increases reported autonomy while decreasing reported acceptance of domestic violence and son preference. In some cases, the effects are equivalent to what can be achieved with five additional years of schooling.

Not just in rural India, but also in urban Bangladesh can TV have similar effects -- that's what Aanmona Priyadarshani and Samia Afroz Rahim find in a study published in 2010.2 They analysed the TV viewing patterns of women aged 15-45, from different economic and social backgrounds, occupations, marital status and locations. Those surveyed included housewives, university or college students, as well as women working as domestic help, day labourers or factory workers in the garments sector. The authors conclude: "… viewers may find comfort in narratives that reinforce existing power structures because it is so familiar to their realities, the spaces that television offer for escape, fantasy and participation all lead to a reconfiguring of their lives through women's conscious and active selection and enactment."

No one made "Kyun ki saas bhi kabhie bahu thi" with women's rights in mind. In fact, shows like that are typically atrociously sexist productions, conforming to the most stereotyped gender roles in our society. But nonetheless, it seems that even shows like that can contribute to important social changes. Imagine then the positive power of TV when it is used consciously to assist social reforms.

Indeed, there is a rich history of TV heralding socio-political changes around the world. Sesame Street and its regional derivations have taught inclusion and harmony to generations of children over the past few decades. When the ordinary people behind the Iron Curtain tuned into western channels and discovered that the exploitative west offered a better lifestyle than their so-called 'workers' paradises', the fall of Berlin Wall became just a matter of time -- JR Ewing may well have been the greatest American general! And far closer to our time, Al Jazeera is playing as big a role as Facebook in the Arab Spring.

To be sure, not every socio-political change is for the better, and TV can also make for retrograde/reactionary politics. An example may be the screening of Hindu epics on state-run Indian TV in the late 1980s, which is deemed to have assisted the rise of the Hindutva politics at the expense of the country's secular forces.

|

ZAHEDUL I KHAN |

There is no doubt that television can be an agent of social and political change in Bangladesh. Or it could be, if our producers were not so heavily focussed on talk shows. Of course, the economics of entertainment industry means it makes perfect sense that talk shows are so popular among producers. In the entertainment business, it is generally impossible to predict what people want. Typically what happens is that the production house tries a number of programmes (or movies, or albums), only one of which is a hit, and then this has a large number of imitators until the market saturates and something else hits.

This is why in the west we saw glam soaps like Dallas-Dynasty (and BTV equivalents like Shokal Shondhya) rule the airwave in the early 1980s, sitcoms boom in the mid-1990s and reality TV phenomenon of the last decade. Similarly, music industry or movie industry goes through phases when everyone follows a particular formula. Indeed, this formula-chasing is as old as the industry itself. Shakespeare wrote 37 plays, of which Romeo and Juliet was 28th. It was his first where the leading couple die as a result of some misunderstanding. This turned out to be his biggest hit, and he had multiple deaths in four of his remaining nine plays.

In today's Bangladesh, the particular hit formula for TV is talk shows. While talk shows don't appear all that likely to result in positive social transformation, television current affairs programmes have been dramatically altering politics in the country. Once upon a time, our politics was dominated by the parties that controlled the street. This has been changing for a while. In the lead up to the 2001 election, Dr Badruddoza Chowdhury's Shabash Bangladesh contributed heavily to the BNP's campaign. During the BNP-Jamaat era that followed, opposition parties found no quarters in the streets. But the news footage of successive terrorist acts and assassinations portrayed the government as a patron of Islamist militancy. And then, the images of its heavyweights in handcuffs on corruption charges percolated around the airwaves for two years leading to the 2008 election. Meanwhile, the images of the Dhaka University riots of August 2007 unravelled Gen Moeen's designs on power.

These days, every statement made by a senior politician from either side of the aisle, every gaffe committed by either parties, every news to break, every incidence to happen, are already dissected every possible way over the 24-hour news cycle. And this will only accelerate with new channels, and technology such as cellphone based web TV.3 Street fighting is giving way to air wars.

And this makes it crucial to understand who is allowed to enter the television market, and who is forced out, and why. Using legal loopholes, the BNP-Jamaat government shut down the Ekushey TV. The military-backed 1/11 regime shut down CBS, a 24-hour news channel after the August 2007 riots. The current government has carried on this trend. Meanwhile, new channels open, under successive governments. How transparent is the process? Why are certain applications successful when others fail? Who are funding these new channels? Are they attracting foreign investment like Ekushey did from Citibank? Or are they raising their funds from domestic capital market? Is Bangladeshi market large enough to have two dozen channels?

These questions need to be answered, for the future of our country depends on them.

1. Jensen R and Oster E (2008), The Power of TV: Cable Television and Women's Status in India by Robert Jensen and Emily Oster, NBER Working Paper #13305.

2. Priyadarshani A and Rahim SA (2010), Women watching Televistion: surfing between fantasy and reality, IDS Bulletin.

3. Budd J (2010), A special report on Television, Economist, 29 April.

Jyoti Rahman is a blogger and writes with Drishtipat Writers' Collective (www.drishtipat.org). He can be contacted at jyoti.rahman@drishtipat.org.