Inside

|

Our Migrant Workers:

Hands that Feed the Country

The Libyan crisis has taught us the importance of a national

plan regarding migrant workers, articulates ZIAUDDIN CHOUDHURY.

In a recent VOA Bangla programme on the Libyan crisis that I participated in, among many issues discussed was the fate of Bangladeshi migrant workers in that country. What will happen to 60,000 odd Bangladeshis who like other hapless foreigners have been caught in the middle of a civil war raging in that country? At the time when the issue was being debated in that VOA program, some of the Bangladeshi migrants had been either been evacuated or were in the process of being rescued from there with help from the International Organization for Migration (IOM). But thousands of others who had travelled hundreds of miles using all kinds of transports to the Libyan borders were still stranded there.

It was not a pleasant sight to watch the milling crowd of migrants in makeshift tents surviving on a minimal ration of food and waiting for external intervention for their rescue. This was a sorry sight as it involved a segment of our people who had staked their all to work in a foreign land for earning a livelihood, not only for themselves, but also for their entire families that they had left behind in the country. A question that arose in that VOA discussion was what would happen to these thousands of displaced workers when they return home. Will government doles and IOM support compensate their losses? Will they find any employment back home?

The Libyan crisis once again brings to focus the sustainability of our foreign remittances and their continued support to income generation in the country. When a crisis as in Libya forces thousands of foreign workers out of that country and renders those jobless, what is the guarantee that our migrant workers in other countries may not face a fate of a similar kind at one point or another? What will happen to our golden goose that had been laying eggs to sustain our economy for the last four decades?

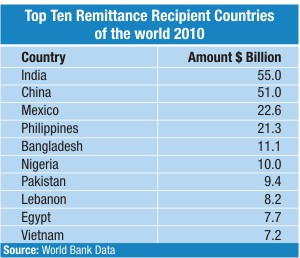

Foreign remittances, rather money sent by our migrant workers from abroad -- especially the Middle East -- now account for the largest chunk of our foreign earnings. Today Bangladesh is among the top 10 foreign remittance recipient countries of the world, receiving over $11 billion in 2010. But this is an official figure. Unofficial estimates of remittance are nearly twice this amount since much of the remittance home is through private channels. These are earnings of our workers, close to seven million of them, spread over 140 countries of the world, with nearly two thirds being concentrated in the Middle East and Near East. Forecasts for these earnings are rather cheerful. If the current growth trend continues (which has averaged nearly 20% annually in last 30 years), foreign remittances will be twice that of our foreign exports earning in next 10 years. But will this really hold? What support do we have to sustain this source of revenue?

Foreign remittances, rather money sent by our migrant workers from abroad -- especially the Middle East -- now account for the largest chunk of our foreign earnings. Today Bangladesh is among the top 10 foreign remittance recipient countries of the world, receiving over $11 billion in 2010. But this is an official figure. Unofficial estimates of remittance are nearly twice this amount since much of the remittance home is through private channels. These are earnings of our workers, close to seven million of them, spread over 140 countries of the world, with nearly two thirds being concentrated in the Middle East and Near East. Forecasts for these earnings are rather cheerful. If the current growth trend continues (which has averaged nearly 20% annually in last 30 years), foreign remittances will be twice that of our foreign exports earning in next 10 years. But will this really hold? What support do we have to sustain this source of revenue?

There were considerable worries of a dip in foreign remittances when global economic crisis hit the developed nations including the oil rich countries two years back. Apprehensions of millions of migrant workers rendered jobless and forced to return home were building fast. Experts viewed Bangladesh as one of the countries that would be hit hard if the predictions came true. Fortunately we have weathered that, as neither the number of migrants nor the remittances from them went to a downward spiral. In fact the cumulative growth in migrants and the level of employment in the Gulf Countries helped us to tide over the apprehended crisis. A new migrant worker on average adds about $816 to the foreign remittance annually.

With the global recession expected to be on its way to be over, we can be hopeful that Bangladesh will continue to maintain its predicted growth in foreign remittance. But is that a bankable expectation? Should we not prepare ourselves in case continued deployment of our migrants abroad does not happen, or we have hordes of such migrants suddenly returning home?

It may not sound possible in the current rosy environment, but it is plausible that thousands of workers like the kind stranded in Libya are repatriated home with no jobs at home and little savings. The Libyan crisis has taught us that we need a national plan to deal with such unforeseen emergencies. We need a plan that not only caters to deployment of workers abroad, but also to their sustenance and gainful employment when they return home -- either voluntarily or involuntarily.

|

RASHED SHUMON |

While addressing this rather unpleasant and unwelcome scenario, several obstacles come to mind immediately that we need to address and overcome. Key among these are lack of a national database on migrants (who they are, their skills, where they have gone, their employers, etc.), strengthening of the institutions that help the migrants in their deployment abroad (with rigorous supervision of the recruitment agencies), and lack of a national plan that can help rehabilitation of the workers once they return. Added to these are continued reluctance of a majority of the migrant workers to remit money through official means and lack of willingness to invest money in government sponsored institutions.

Today any estimate of workers abroad is mostly a guess work since the number is obtained by the government from recruiting agencies. The number of workers in Libya, for example, was cited anywhere from 60,000-75,000. The total number of migrant workers is variously estimated at anywhere between 600,000 and 700,000 (a gap of one hundred thousand!). Official estimate of money received from these workers is $11.1 billion, but we are told the amount could be twice that since much of the remittances are sent by unofficial channels. Much of the investment of these workers is for unproductive purposes adding little employment opportunities either for them or for their fellow countrymen.

We set up a Ministry of Expatriates Welfare and Overseas Employment many years ago for enhancement of overseas employment and to ensure the welfare of expatriate workers. The objectives of this institution are all laudable, but none of it will be of value to the workers when it cannot respond adequately to a crisis as in Libya recently. The ministry perhaps has done a better job in coordinating recruiting agencies and working with foreign governments in labour supply than in finding ways and means to help the returning workers rehabilitate back home and advising them on productive investment.

Our government and the institutions set up to serve the migrant workers' interest need to do more. First off, they need to set up a live, up-to-date functioning database of migrant workers that can serve as a reliable source of information on the expatriates. This can be done with the help of IOM. Next, the Ministry of Expatriates Welfare should find ways with support from our commercial banks and the Central Bank to attract remittances through official means. The Ministry needs to examine if the reasons why the workers chose unofficial means are because of rate difference, speed of remittance, or other bureaucratic hurdles. The Ministry also needs to see why the government sponsored financial institutions cannot attract investment from the expatriates. Are there other ways to help the migrant workers to choose their investment back home that they can fall back upon when they return? Can there be innovative ways they can employ their hard earned money back home? And above all, can we develop a plan to deal with the crisis of sudden lay off from work for thousands of workers?

Our migrant workers went abroad, most times because they had no productive employment back home. They went abroad at a great financial cost, and at times risking lives, for a livelihood. What they earned not only helped to pay off their debts and supported families, but also increased our coffer of foreign currencies. We owe it to them to help find them back on their feet when they return, either voluntarily or involuntarily.

The VOA debate on how to compensate a displaced migrant worker and rehabilitate him or her becomes all the more important when we accept that a repeat of Libya experience can happen anywhere where we have our workers. We can perhaps find alternative work places in another countries for a few thousand, but we cannot expect hundreds of thousands to find jobs at a time if they are suddenly unemployed in the countries where they work. They will return and will be a charge to the government. It may not happen right away, but we must be aware that such a possibility may arise. We need to prepare ourselves for that.

Ziauddin Choudhury works for an international organisation in USA.