Inside

Original Forum |

| The Way Out? -- Ali Riaz |

| Rule by Brute Majority? -- Dr. Mizanur Rahman Shelley |

| Movements, Motion, Motives: Students in politics -- Shahana Siddiqui |

| Can Parliament be more than a Rubber Stamp? -- Saqeb Mahbub |

| Politics of Intolerance and Our Future -- Ziauddin Choudhury |

Kony 2012 and the New Age of

Social Media in Political Action --- Olinda Hassan |

The Dance between Education, Politics and the State --- Shakil Ahmed |

New Leadership - Is it forming? -- Shahedul Anam Khan |

Confrontational or Infantile Politics? -- Syed Fattahul Alim |

| Politics of Religion and Distortion of Ideologies -- Kazi Ataul-Al-Osman |

| Politics of Judicial Appointment --Ahmed Zaker Chowdhury |

| Priority of the Media: Profit,

politics or the public? -- M. Golam Rahman |

| Mujibnagar and Our Twilight Struggle --Syed Badrul Ahsan |

The Dance between Education, Politics and the State

SHAKIL AHMED examines the use and abuse of politics within the education system.

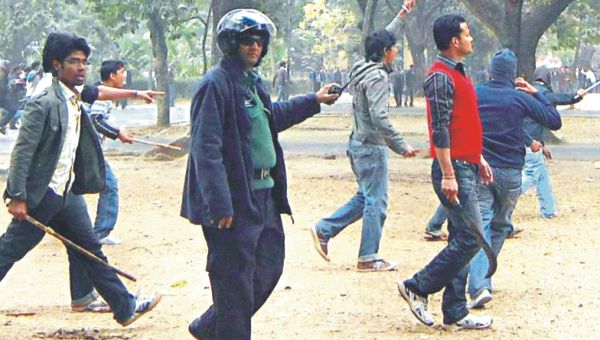

On the 22nd of March, 2012, a staff correspondent from a local English daily reported: "A man died and 20 others were injured yesterday in a two-hour long clash between students of Jagannath (JnU) and traders of Patuatuli Market." According to the report, the clash started since six students from JnU, who were members of the Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL), the student wing of the Awami League (ruling party), were not allowed to take six sunglasses from a shop for free and in response, these students stabbed the shopkeeper and a customer.

On March 25, 2012, United News of Bangladesh reported: "A local leader of Jatiyatabadi Chhatra Dal, student wing of the Bangladesh National Party (opposition party), was killed in an attack by miscreants on Kalibari road in the city on Saturday night." On the same day, a correspondent of a local English daily reported, "A number of Jahangirnagar University teachers teamed up as Shikkhak Samaj on Saturday, locked up the office of the vice-chancellor and sat in there for two hours demanding immediate resignation of the vice-chancellor." Again, according to the report, the teachers claimed that the vice-chancellor of the university has no right to remain in his post as he is still patronising BCL activists who tortured a fourth-year English student on January 8. The student died on January 9 due to sustained injuries.

People who are reading these words are most likely aware of how intertwined politics and education have become not only in Bangladeshi society, but even in most parts of the world as well. The idea that education can be used (or abused) as a tool for achieving political goals is not necessarily a new one. While modern examples of this relationship can be highlighted, we can look at how even the British attempted to influence educational policy for their own gains in colonised India.

Colonial control of education

In 1835, Thomas Macaulay, architect of Colonial Britain's education policy in India said, "We must do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern, a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, words and intellect."

Echoing Macaulay's sentiments, J.N Faquhar wrote, "The new educational policy of the Government created during these years the modern educated class of India. These are men who think and speak in English habitually, who are proud of their citizenship in the British Empire, who are devoted to English literature, and whose intellectual life has been almost entirely formed by the thought of the West, large numbers of them enter government services, while the rest practise law, medicine or teaching or take to journalism or business."

In Bangladesh, who actually makes up the "educated" class is a debate on its own. However, the question remains -- is it all right to assume that the influence of British Education policy still persists? Have some components of Western philosophy directly or indirectly influenced the minds of politicians, government officers, lawyers, doctors, educators, journalists or businesspeople?

The foundation of Western Philosophy

Aristotle, the Greek philosopher who lived during the 4th century BC, is considered to be one of the founding pillars of Western thought, since influences of his philosophies can be seen even today in various sectors of life -- economics, politics, sciences, ethics, etc.

During his time, education used to follow a guru-shirsho model, where there were no grades, no exams, no certificates or primary and secondary school notions -- there would be one teacher (guru) and the rest of the students (shirsho) would follow the teachings and the way of life of the teacher. At times, the students would even live together and with the teacher.

However, Aristotle used to advocate for an educational model, where the state would be in charge of education. For Aristotle, the goal of education was identical to the goal of a man. Since man's goal, according to him, was the pursuit of happiness and the happy man is a virtuous man, a good man, Aristotle mentions in the Nichomachean Ethics that: "The man who is to be good must be well-trained and habituated."

Since the state is in charge of maintaining and ensuring stability in society, Aristotle argues in his Politics, "The most powerful factor of all those I have mentioned as contributing to the stability of constitutions, but one which is nowadays universally neglected, is the education of citizens in the spirit of the constitution under which they live. You may have an unsurpassed legal system, ratified by the whole civic body, but it is of no avail unless the citizens have been trained by force of habit and teaching in the spirit of the constitution."

Here, Aristotle is not supporting any particular form of constitution. Whether it is a democracy, a monarchy, a theocracy or an oligarchy, whoever is in charge of maintaining law and order must be in charge of education. Aristotle goes on to say, "No one can doubt that it is the legislator's very special duty to regulate the education of the youth, otherwise the constitution of the state will suffer harm. The citizen should be trained in accordance with the particular form of government under which he is to live; for each type of constitution has a distinctive character which originally formed it and makes possible its continued existence...again some preliminary training and habituation are required for the exercise of any faculty of art; and the same therefore, obviously to the practice of virtue."

Aristotelian influence

Since Bangladesh's independence in 1971, the State has been primarily in charge of education. During the present Awami League government, educational plans from the State have been implemented through the Ministry of Primary and Mass Education and the Ministry of Education. While there are private educational institutions and non-governmental institutions, the government does have some influence on these systems as well.

Whether through the British or the Pakistani systems of government, Aristotle's notion of the state being in charge of education has had influence on how the idea of how the Bangladeshi State is now in charge of education. Of course, it has not been a smooth ride for any of the post-independence governments to handle the education system. Allegations of corruption, political biasness, drops in quality of education, session jams, changes in educational content in accordance with the change in ruling political parties, cheating and altering results during national examinations, violence related to student political parties as mentioned above, and a myriad of other problems have marred the education system -- issues arising in institutions across all the educational levels -- primary, secondary and tertiary. In the midst of this all, political elements are usually blamed for being an important root to all these problems, since after all, those who are in charge of the State have to play the political game in order to be in power.

In the modern context, advocates of social progress, however, think that the State should not necessarily be in charge of education. Aristotle, though, used to think that any change is not desirable in itself since any change may lead to 'corruption' of the system. What happens in the situation when corruption may already exist within the system?

Contradicting Aristotle

Cai Yuanpei, a renowned liberal educator of early 20th century Chin, the Republic's first Minister of Education and Chancellor of Beijing University, criticised the traditional system of education heavily and claimed that its aim was bi (vulgar), since it mainly focused on teaching students how to pass the civil service examinations. He called it luan (disordered) since there was nothing designed for children's needs in particular and for human development in general.

In addition to calling the system fu (superficial -- based on rote memory), zhi (discouraging) and xi (fearful), Cai also called the system qi (deceptive), since the outcome of the civil services examinations were usually not useful. At the end of the day, "selected bureaucrats formed a privileged caste who took care to shield one another", a scene that is reminiscent in Bangladeshi society, where in some areas, people build political alliances in order to get promoted within their workplace, political parties or even student societies. In situations like this, the political alliance seems to prevail over meritocracy.

One of Cai's plans to democratise education came in direct conflict with the "Nationalist aim to unite China under its centralized political power", which eventually led to the failure of that particular project. In times like this, Cai used to feel that the impact of party politics in education was too prevalent for him to make any influence.

In order to address such situations, he stated, "Education is to help the taught obtain the abilities to develop the intelligence of mind, and perfect personal traits that contribute to the culture of humankind; but the education is not to make the taught a special instrument used by others who have some other kind of purpose. On that ground, the enterprise of schooling should be entirely given over to independent educators, uninfluenced by any political party or church."

Should our system in Bangladesh then be independent from political parties and thus, the State? If that's the case, should we stop believing in Aristotle's view?

Taha Hussein, one of Egypt's greatest 20th century intellectuals did not see eye-to-eye with Aristotle's view of education. He said, "Aristotle was guilty of a grievous error when he asserted that some are born to command and others to obey. Never! We are all born to be equal in rights and duties to receive the benefits and burdens which fall to our lot in this life. When oppressors rise above the people, it is we ourselves who must cast them down; and when tyrants emerge, it is we ourselves who must remove them."

Dealing with oppression

Just because people are in charge of education systems, does it make them oppressors or tyrants? Rabindranath Tagore, renowned poet and intellectual, claimed, "Our so-called responsible classes live in comfort because the common man has not yet understood his own situation. That is why the landlord beats him. The money-lender holds him in his clutches; the foreman abuses him; the policeman fleeces him; the priest exploits him; and the magistrate picks his pockets."

If such is the case, can't the responsible classes just change their attitudes? Can education help them change? But wait, aren't they the ones influencing the education system itself?

Greek philosopher and educationist, Dimitri Glinos claims, "Our system of education is dominated by all levels, by an elitist and retrograde attitude. Elitism is interested only in the minute proportion of students who will go on to obtain a university degree. Our concern and attention are direct towards them. Let the other 90% be sacrificed for this select few, let the rest of the nation be intellectually stunted for the benefit of the elite. The elitist spirit has left the working class in darkness and the lower-middle class in a state of semi-ignorance."

Hussein adds, "Though the circumstances of history may have divided them into rich and poor, and though nature may have divided them again in terms of capacity and ability, yet there is one thing that they share and is the same for all of them: in the saying of the Prophet, they are human beings; from dust they have been created and to dust they shall return. Therefore, leaders and rulers, lords and masters must rid themselves of any notion that they are superior to the people; they must rid themselves of any sense that they are doing a work of charity, for such charity is but one facet of superiority. These notions must be replaced by a belief in equality and justice among the people."

Maybe it is this feeling of superiority that sustains some of the troubling issues within education: the violence, the corruption and the confidence of some students and teachers, who may or may not have political power and backup, to get away with whatever injustice they perform or they instigate others to perform. Such negative attitudes and feelings cannot simply be changed by appealing to religious sentiments, Tagore thought -- education eventually has to be the way.

Back to the future

Instead of disbanding student political parties in Bangladesh as some have suggested, on the 11th of June, 2011, the BSS reported that the government held elections of Student Councils at 600 primary schools, given that the pilot project for student councils in 100 schools was successful.

The Prime Minister's private secretary, Md. Nazrul Islam Khan said, "We are frequently witnessing clashes and violence centering the activities of student councils at college and university level, as they (students) were never taught how to practice democratic norms, show tolerance to other opinions and true essence of leadership at school level. The election of student council will build up an attitude among the students of practicing democracy and they will learn that in a democratic environment everyone must accept people's verdict willingly."

This does beg the question, how does one actually assess the people's verdict? Is it through the traditionally practiced concept of 'majority wins'?

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi laments, "I do not believe in the doctrine of the greatest good of the greatest number. It means that, in its nakedness, in order to observe the supposed good of fifty-one percent, the interest of the forty nine percent may be or should be sacrificed. It is a heartless doctrine and has done harm to humanity. The only real dignified human doctrine is the greatest good of all."

Only time will tell whether Student Councils and such projects by the state will be successful, while others may critique that such projects groom student politicians in primary schools to provide a supply of minions for political parties in the future. While student politics remains rampant and dirtiness in politics continues to play a degrading role in education, it is hoped that the different perspectives from the thinkers will make the readers understand how the state has come into its role of being the organiser of education, how political interests influence the State and that a change in values may eventually lead to a change in how people are influencing the system.

At the same time, initiatives to make education systems more autonomous can be taken in the hope that politics will no longer be part of the educational equation. Without a change in values though, such initiatives are also likely to fail (as in Cai's case).

If all of us are collectively able to take the right steps in the future by learning from ourselves and others, then maybe one day we can be nearer to Tagore's view of education: "In every nation, education is intimately associated with the life of the people. For us, modern education is relevant only to turning out clerks, lawyers, doctors, magistrates and policemen. This education has not reached the farmer, the oil grinder, nor the potter. No other educated society has been struck with such disaster. If ever a truly Indian [undivided South Asian] university is established it must from the very beginning implement India [undivided South Asia]'s own knowledge of economics, agriculture, health, medicine and of all other everyday science from the surrounding villages. Then alone can the school or university become the centre of the country's way of living."

Shakil Ahmed is a staff researcher at the Institute of Educational Development, Brac University.