Inside

|

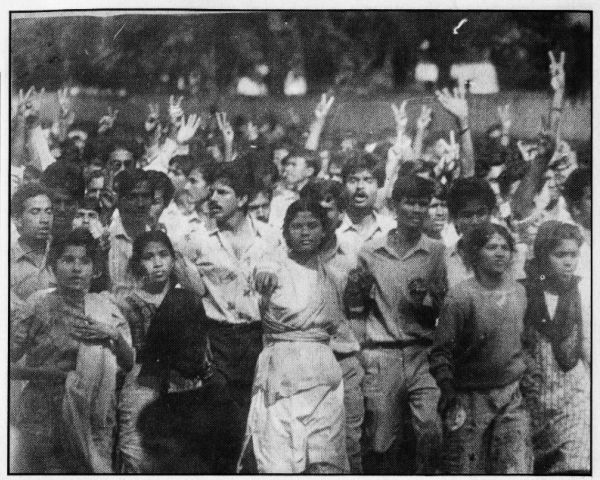

Movements, Motion, Motives: Students in politics

SHAHANA SIDDIQUI ponders over who is to blame for the sorry state of student politics today.

Student politics: Past glories, present shame

There are stories of how brothers stopped speaking to each other for months because of their allegiance to different communist party wings. There are stories of female student leaders encouraging their girlfriends to join politics at a time when women had far less freedom. There are stories of getting expelled from Dhaka University for standing up against dictators. There are stories of boys and girls standing next to political giants as they changed the history of Bangladesh. There are stories of fearless youth at the forefront of firing squads, giving their lives for language and land. These are the stories of student politicians, stories of legends.

While a significant part of Bangladesh's history was contributed by students who were in politics, 41 years down the line and the attitude towards student politics is very different. Now the stories are that of "bhalo ghorer chhele-meyera politics e naamena". Student politics is "dirty" and "disgraceful" and no self-respecting person should ever join such groups. Many will go as far as to comparing the current student political groups as the Bangladeshi version of gangs, who are uncontrollable, part of organised crime, and infesting violence and destruction. Yet in the same conversation as denouncing student politics in Bangladesh, the bhodro shomaj will ask: "Bhalo [political] alternative koi? Ei juger chhele-meyera politics' e ashchhena keno?" Where are the future leaders -- as if Gandhis and Mandelas appear out of nowhere!

What the exasperated generation tend to forget is that while everyone is protecting their own child and looking at someone else to take upon the mammoth task of "fixing" the state of politics in Bangladesh, the real thugs and mastaans are entering the political arena by the dozen, affecting our daily lives and social fabric. The dynastic nature of politics also discourages middle class families to view this as a lucrative career for their children but at the same time, there is a general feeling of helplessness with a vacuum in the second and third tier of political leadership in the major political parties.

Understanding students and their politics

Students who are involved in student politics are usually viewed as miscreants and nuisances. There is a tendency to immediately blame the student politicians for their (mis)conducts and (mis)deeds. While we know very well it is the same politicians that we are voting for, being sycophants towards, are the very people who are ordering and financing students' "activities", we blame the puppets rather than the puppeteer.

And for those who are not in politics, there is a disconnection and disinterest towards national politics. While Bangladeshis are addicted to all things politics, the urban elite students, particularly in private universities, are found to be detached from political processes. Private universities were founded on the belief of non-partisan politics for students on campus to move away from the session jams that deteriorated the standard of education at national universities. Through this process, however, private university boards created apolitical and apathetic student bodies who have very little to do with national challenges and pressing concerns.

On the other side, students at national universities involved in politics are considered to be hooligans and disruptive elements to academia and political process. There are several articles and books condemning student politics and their decline over the decades, especially after the fall of Hossain M Ershad and the rise of partisan politics in Bangladesh. Yet, despite the general consensus regarding student politics, at times of autocratic regimes, we look to the students and their ability to mass mobilise to stand up against the status quo, to be destructive on behalf of the nation, to restore democracy.

But who exactly are these student leaders and what influenced them to join politics in the first place? While civil society condemns these student politicians for their violence, there is also value in understanding why these young men and women entered these student wings in the first place. Perhaps by engaging with the current leaders, we would be able to find ways to restructure and rejuvenate the student wings into more constructive activism.

To understand more on the current state of student politics, Monir Uddin, a post-graduate student and I are carrying out a series of interviews with different youth political leaders affiliated with the political wings of Bangladesh, to better understand their views and convictions for what they do. This is the initial stage of a more comprehensive research initiative on the current state of student politics and youth movement (or the lack of) in Bangladesh.

In this article, we present our initial conversations with three student leaders of the Chhatra League, Chhatra Dal and Chhatra Front. They were all asked as to why they joined politics, what their activities are as student leaders, what they are studying, what socio-economic backgrounds they are from and what their aspirations are for the future.

Interview 1: Leader A -- Bangladesh Chhatra League

Leader A comes from a middle-income family where financially they were always stable. He joined politics since his high school days because of the neighbourhood boro bhais who were already in political wings. In 2000 he got admitted to Tejgaon College and University and by 2005 he had gone from being co-chair of Chhatra League Committee to becoming currently the Joint Secretary of Chhatra League as well as co-chair of Chhatra League North Dhaka. When he first came into student politics, the level of animosity was not this bad. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was of course an inspiration but he was directly inspired by Faridur Rahman Khan Iran, a veteran student leader.

The interesting case about Tejgaon College and University is that irrespective of which political party is in power at the national level, students from different political wings are able to get an academic position/seat as well as actively practise their politics of choice without interference from the current political power.

To better understand Leader A's political outreach and exactly how he mobilises others, we asked a series of questions regarding his daily routine and activities. He is at the university premise by 9am and goes to his classes as per schedule. On days he does not have any classes, he still hangs around the university, checks up on the younger students to "inspire" them into becoming active members and attends to any major problems or pending requests. The majority of teachers are very well-known to him and they maintain a close relation to Leader A. His relations with both students and teachers provide him with the network of information that is needed to retain his position and the status quo at the university. He is the "boro bhai" who looks out for others and whenever any of his junior political "boys" are in trouble or unwell, Leader A " raises" funds for them through various connections and means. If there is no political activity in the evening, he hangs out with his friends.

Recently, Bangladesh Chhatra League passed a new policy that to be a student leader one has to be below the age of 29 and cannot be married. While Leader A welcomed this decision from the central level, he did not say anything regarding the fact that he was well above 29!

When asked about the difference between politics when he first joined and the situation now, he answered that currently, the animosity is greater and so is the hooliganism and vandalism. Some of this destructive behaviour is also due to the constant shortage of funds. Leader A candidly suggested that regular funding from the central party was very much needed for student politics to transform to a mature stage. An extensive budgeting process with detailed work plan should be submitted to the central committee, based on which fund allocations will be carried out.

When asked about his own political ambitions, Leader A explained that he wants to do his own business and in the near future, become a Member of Parliament under the Awami League banner. He is constantly in touch with his political guru Iran Bhai and he loves the networking aspect of politics where he gets to meet new people and have a direct influence over many.

Interview 2: Leader B -- Jatiyatabadi Chhatra Dal (this interview was done over the phone so more details in the near future)

Leader B entered as a fresher in Dhaka University in 2000 and is still far from completing his Masters. He is majoring in Bangla. Coming from an army family, money was never the driving force for him to join politics but rather, power and its accessibility have been the driving forces for Leader B to join student politics. He likes the fact that he is the boro bhai of the local area and that people respect him, and he does not mind investing his own money to be in politics.

When he first joined as a junior in Chhatra Dal, he was engaged in a number of student-led disputes. But as he went up the ranks, the less he had to be involved with the destructive sides to student politics. He explained that when one goes up the ranks, it is more about maintaining networks and lobbying for the party. During the BNP era he consciously provided protection for one of the senior Chhatra League students because of which now, during the current Awami League government, Leader B remains unharmed and in fact, well-respected among peers.

He explained that this is not only a practice among student politicians but a standard practice for politics in Bangladesh in general, that as one goes up the ladder, the disputes subside and people help each other out irrespective of political party allegiance. The destructions are carried out by the young ones, the juniors; it is almost a part of their inception process, to maintain an image of animosity and frustration.

Currently Leader B is working as a tutor but is looking for work that will allow him to do politics. Once in a service holding position, Leader B will be unable to give time to his political career. He is waiting for BNP to come back to power so that he can find (or create) that perfect position which will give him a job as well as the flexibility to remain in politics.

When asked why he joined Chhatra Dal as opposed to any other political wing, he explained that the area in Chittagong he is originally from is predominantly a BNP area. Leader B's father had run for local elections earlier from the BNP platform. From that experience he recollects that while everyone in the community respected his father being an honest man, by the end of the day, honesty does not get one very far in Bangladeshi politics -- "joto beshi shoth thakba, totoh beshi loss khaba".

Interview 3: Leader C -- Chhatra Front

Leader C joined politics as early as 1998 and is now one of the most influential people within his political wing. When he first joined Chhatra Front in Chittagong University, Shibir was not so strong, and hooliganism was not so rampant. Instead, issue-based politics and the overall intellectually stimulating aspects of Chhatra Front attracted him to join this political wing.

That time is long gone and now he realises that doing politics is solely about power and maintaining that power structure. Young boys find a sense of security through the political wings and as a big brother, he provides that social capital. Elections are more like festivals now instead of a democratic process through which representatives are chosen to lead the country. Hence, Leader C thinks that it is through social movements that he will come to a position of power.

Leader C is an interesting case where he is not about his own personal glory because he sees the system as being corrupt in general and the rise of one person will not change the inefficiency in the larger system. Instead, he is solely dedicated to the organisation's momentum and unity.

As for funding options to keep that momentum and unity, he "raises" funds through networks and personal relations, even donates a portion of his tuition when needed. Revenue is also earned from selling the political newspaper. He attends all political meetings and gatherings as instructed by the central committee and also organises events.

Leader C feels that student politics is no longer about ideology but rather about access to power, money and arms. Young impressionable students join politics because of a lack of a viable alternative in the country.

Quick and dirty analysis

While these three accounts should not be the basis for generalisation, it was interesting to find deep commonalities in all three of the student leaders' takes on politics and movements. To begin with, all of them are from financially secure families, so it is not money that they are after but the sense of being someone. This is something I personally observe among various people that I work and interact with -- given the strong class-oriented society of Bangladesh where it is not only about economic position but social standing, people have a strong desire to be "someone", to be a part of that exclusive elite strata, and to put it crudely "jaate utha".

The strong class divides and this desire to be someone in society are the ingredients for a strong patronage-system where the juniors are in it for some form of security and the older ones feel a sense of power and are almost godfather-like figures to the young ones. This relationship is introduced and practised from the very high up and trickles down to the very grassroots of politics in Bangladesh. The question, therefore, is how effective will it be for students to break out of this system of patronage when the entire national political structure is deeply rooted in a perverse neo-zamindari system?

The other common thread is that of chipping away of political ideologues and acceptance of politics as a means to enhance business and career paths. It is an open secret that reasons for forming government is to have easy access to business. One of the student leaders admitted that his party members were heavily connected to government tender bids because that is one of the ways that the central committee keeps financing the student wings. One of the reasons for the intertwining of business and politics is because of the absence of structured campaign finance in Bangladesh. Truth is, to do politics anywhere in the world, one needs money. The days of joining politics for ideology's sake are long gone and in the practical world, everyone needs money to survive. In developed countries, political parties have core funding from various big and small funders who will pay for the political strategist, the communication team, the campaign manager and of course the army of interns who will keep the phones ringing, the emails going, the Facebook posts up and furiously Tweeting on their political leader's achievements and gains. For some reason (I see this especially in the development sector), there is a strange notion among us Bangladeshis that people should just work for free or minimum wage when it comes to anything to do with the poor (which is the main target group for both politicians and development sector!). And as a result, of course no one works for free, so we have corrupt ways of raising the funds and keeping the campaigns going.

I would therefore like to conclude by again asking the question with which I began this article -- why do we blame the puppets when the puppeteers are our political leaders and to a large extent -- ourselves? How many young boys and girls outside of our own families do we provide any financial or social security to so that political leaders are unable to get to them first? How many recreational options have we created for the teens with which they will remain busy instead of getting attracted by the neighbourhood thugs who are also politically connected? How many times do the civil society giants who were student politicians themselves in the '60's and '70's, pay visits to their political alma maters to understand the current challenges and struggles instead of passing broad judgments and statements on the state of student politics in Bangladesh?

Shahana Siddiqui, is the co-founder and editor of The Bangladeshi, a youth-based free political thinking platform. Special thanks goes to Monir Uddin, a researcher and core member of The Bangladeshi. www.thebangladeshi.org. They can be reached at: bangladeshi.pride@gmail.com