Inside

Original Forum |

| The Way Out? -- Ali Riaz |

| Rule by Brute Majority? -- Dr. Mizanur Rahman Shelley |

| Movements, Motion, Motives: Students in politics -- Shahana Siddiqui |

| Can Parliament be more than a Rubber Stamp? -- Saqeb Mahbub |

| Politics of Intolerance and Our Future -- Ziauddin Choudhury |

Kony 2012 and the New Age of

Social Media in Political Action --- Olinda Hassan |

The Dance between Education, Politics and the State --- Shakil Ahmed |

New Leadership - Is it forming? -- Shahedul Anam Khan |

Confrontational or Infantile Politics? -- Syed Fattahul Alim |

| Politics of Religion and Distortion of Ideologies -- Kazi Ataul-Al-Osman |

| Politics of Judicial Appointment --Ahmed Zaker Chowdhury |

| Priority of the Media: Profit,

politics or the public? -- M. Golam Rahman |

| Mujibnagar and Our Twilight Struggle --Syed Badrul Ahsan |

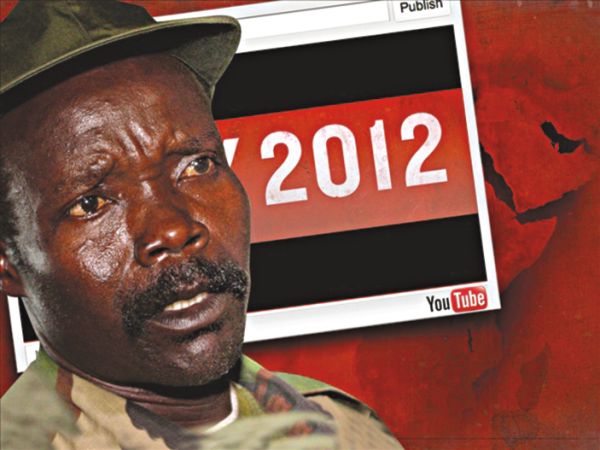

Kony 2012 and the New Age of Social Media in Political Action

OLINDA HASSAN looks at the significance of social media in bringing political change.

Can social media be used to make an effective political change? This question highlights recent reactions by activists, academics, politicians, to journalists in the wake of Kony 2012, the video aimed at bringing public attention to Joseph Kony, the militant leader of the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) in Uganda. The 30 minute video as of March 19 has had 82 million viewers. That is almost triple the population of Uganda.

Joseph Kony led the LRA under the ideology of creating a theocratic state based on the Ten Commandments in Uganda. For over a quarter of a century, Kony built a sizable army of child soldiers and ordered the abduction of thousands of girls to become sex slaves. Though in 2005 Kony was indicted of war crimes by the International Criminal Court, he has yet to be captured.

Kony 2012 was created by a US-based advocacy group, Invisible Children Inc which has long worked in Uganda to bring access to education and quality livelihood to a post-conflict community that suffers from poverty and the memories of war. The video brings to light these issues, with the hope that it will lead to the capture of the militant leader before the end of the year.

Invisible Children Inc has been long known for having one of the strongest social media bases in the nonprofit world. The video's viral purpose is clear as it repeats the images of people using social media tools such as Facebook, Twitter, and of course, YouTube. The video opens with the words "Nothing is more powerful than an idea whose time has come. " Kony 2012 does not necessarily make Kony the celebrity but certainly the bad guy, and more interestingly, it personifies the viewer -- that it is you watching who can bring change. Furthermore, it uses a simplistic story line -- some argue too simple -- and thus, misses some key facts and features of the atrocities committed. However, its simplicity was the reason why the video was able to target so many viewers -- and from so many intellectual and other backgrounds. In an age of technological communication when so many millions of users utilise social media around the world, this is certainly telling.

The simple story line, as mentioned, has been the root cause of a backlash of the viral video. Critics argue that the simplification of the complex issue has instead caused "slacktivism" rather than actual activism. Slacktivism, derived from slack and activism, points to the effort of no effort -- a pejorative term that describes supporting a cause through simple measures, like sharing a link of Facebook, and feeling good about it and not going further. As many have argued over blog posts, advancing awareness and social media alone will not do much to stop the atrocities in Africa, let alone capture Kony. Journalist Anthony Kosner writes, "the radical simplification of the situation in Uganda that makes Kony 2012 such an effective piece of social media is the same thing that undermines it as a piece of political activism." (Forbes).

Social media and international politics

We have entered a new era where social media can and have shown to matter, even in as complex an area as foreign policy. Facebook and Twitter have fueled the Arab Spring uprising, giving both men and women equal footing and voice on some of the most pressing issues of governance. Videos have been coming out of Syria on a regular basis, giving them a chance to be noticed by the outside world. As author Philip N. Howard noted, "It was social media that spread both the discontent and inspiring stories of success... into the Middle East." "Occupy Wall Street" in New York has its roots in social media outlets, the same tool used for similar protests around the United States. Young people around the world have especially been hit with the use of social media and also in actually becoming active. It has become an inspiring and a dangerous tool, mainly because so many people have the access, and thus the voice, regardless of gender, age, socioeconomic status to some extent, or language.

Since the rise of the internet in the early 1990s, the world's networked population has increased from a million or two, to low billions. At the same time, social media became "a fact of life for civil society worldwide" (Clay Shirky, Foreign Affairs). It has involved the average citizens, activists, nongovernmental organisations, students, companies, software providers, and of course, governments. As this new era's communication processes gets more complex and intertwined, the population of users have increased. People have greater opportunities to interact, access information, and take action. The high level of production and sharing of multimedia content makes it even more difficult to suppress information. It is redefining freedom, especially in countries where such rights are limited. This was especially true for Egypt, for example, where outlets such as Facebook and Twitter carried the message of freedom and democracy to help raise political uprising. Democracy found its footing in social networks.

The new wave of political activism through social media has certainly attracted the attention of politicians, who on average are much older and in general, of a different demographic than the average activist (who tend to be younger and more in tune with technology as evidenced by recent uprisings and activities). When protests erupted in Tehran, Iran, the US State Department asked Twitter executives to suspend their scheduled maintenance of the service so it could still be used as a tool for political organisation during the demonstrations. While the Green Revolution in Iran in 2009 may have been the first modern rebellion to be recorded on Twitter, it did not bring down a government. The links between social media and revolutions are still being examined by researchers.

Egypt has almost 10.5 million Facebook users, ranking at 20, ahead of countries such as Japan (25) and Russia (29), and way ahead of other North African countries Algeria (44) and Tunisia (47). Bangladesh is ranked at 55, with a little over 2 million users on Facebook, with users from ages 18-24 making up more than 50% of the users (Source: Socialbaker). Bangladesh is also not new to enforced censorship and social media blocking enforced by the government. It is important to also note that many users of sites like Facebook may originate at one place, but the user may live in a different country, as well as the use of multiple accounts and other glitches.

Social media alone is of course not the main driving force of uprisings -- on-the-field activism is. Rather, social media has been taken up to make people aware and inform them of activities taking place that they can participate in. Certainly, awareness is part of the scheme in bringing in changes.

Regulation and censorship (?)

At first, using the words "censorship" and " media" will inevitably bring in an abundance of negative reactions, especially in the 21st century and in an era of technology and global communication. In terms of social media, however, the debate goes further than initial reactions.

Censorship of social media sites are often compared to the censorship of books, films, or the press -- most people do not support such censorship and social media in some ways fits into the category. But because of the complex nature of social media (where everyone can be an author and everyone can have access), it is hard to directly apply the same principles.

Furthermore, social media sites have been used to both organise mass protests that have fueled success (e.g. Egypt and the Arab Spring) to violence (e.g. instant messaging services facilitated the London riots). False information is notorious for appearing in, and being shared around via social media sites. Twitter users' panic tweets about gunmen attacking schools in Mexico allegedly led to 26 car accidents. There are also notions of social media sites being used to develop and strengthen underground cults and gangs in urban centres, such as in Los Angeles to London.

With no proper means of addressing and defining social media (after all, is it really "media"?), governments are left to do as pleased given the right purposes. China, for one, has been known historically to censor internet content. But as a recent Carnegie Mellon University study has shown, Chinese web users have also cleverly found many ways to access forbidden sites and micro blogs to serve their political or social purposes. Iran similarly has just posed another ban on social media outlets, making it more difficult for citizens to communicate, repressing Iranians instead of empowering them through what used to be an easy communication tool.

Kony 2012 and the new age of internet

Returning to the discussion of Invisible Children Inc, Kony 2012 has become one of the most highly viewed videos of recent times on YouTube. The video has attracted notable celebrities such as Ryan Seacrest, Justin Beiber, Rhianna, Alec Baldwin and Taylor Swift who used their Twitter accounts to spread awareness of the video. Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life Project has reported that the first two days after the video was released online, 77% of Twitter conversation was supportive compared with only 7% that was skeptical. However, since its release, there has also been a massive rise in actually analysing both the video and the content from bloggers and journalists so that since March 7, when the response picked up dramatically, the percentage of tweets reflecting skepticism increased to 17%.

And the criticisms are increasing. Some of the main denigration of Kony 2012 in recent days has been on its depiction of Uganda, and how the events covered in the video was the story of the past, and not the current state of the war-wrecked nation. The image of Africa as depicted in the video was also troubling. "This is another video where I see an outsider trying to be a hero rescuing African children. We have seen these stories a lot in Ethiopia, celebrities coming in Somalia," said Rosebell Kagumire, a Ugandan blogger who explained that the video only showcased Africa as hopeless and constantly needing outside help. A lot of phrases like "white man's burden" have also appeared among blog sites. Social media has both the ability to be used to increase awareness of a topic, and to also increase awareness of the details and critics of the topic itself in a very timely manner, as noted in the case of Kony 2012.

Social media is a very recent, and a very relevant player in today's politics, as evidenced by increased government attention and also, government regulation and censorships. However, social media is also not the "only thing" and can often be misguided. The rules of checking facts, the sources, and basic common sense still applies to tweets and Facebook updates -- just as it does for the press. Perhaps such caution is warranted even more for social media outlets because of its ability to be used by the masses and not just experts. Rather than information sharing, social media has perhaps been more actively purposeful for organising, whether that was in the Arab Spring, or as now with Kony 2012 in leading massive attention to a little known leader in the outside world of Uganda.

Nigerian human rights campaigner Omoyele Sowore states it best like it is: "The Internet has helped revolution; but the Internet is not revolution."

Olinda Hassan is a graduate of Wellesley College, and continues to discusses various musings in her blog at olindahassan.wordpress.com