Inside

Original Forum |

| The Way Out? -- Ali Riaz |

| Rule by Brute Majority? -- Dr. Mizanur Rahman Shelley |

| Movements, Motion, Motives: Students in politics -- Shahana Siddiqui |

| Can Parliament be more than a Rubber Stamp? -- Saqeb Mahbub |

| Politics of Intolerance and Our Future -- Ziauddin Choudhury |

Kony 2012 and the New Age of

Social Media in Political Action --- Olinda Hassan |

The Dance between Education, Politics and the State --- Shakil Ahmed |

New Leadership - Is it forming? -- Shahedul Anam Khan |

Confrontational or Infantile Politics? -- Syed Fattahul Alim |

| Politics of Religion and Distortion of Ideologies -- Kazi Ataul-Al-Osman |

| Politics of Judicial Appointment --Ahmed Zaker Chowdhury |

| Priority of the Media: Profit,

politics or the public? -- M. Golam Rahman |

| Mujibnagar and Our Twilight Struggle --Syed Badrul Ahsan |

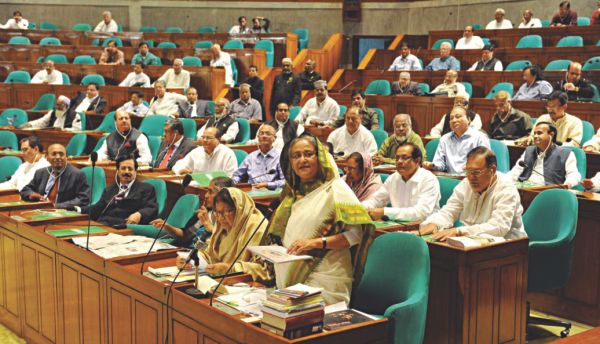

Can Parliament be more than a Rubber Stamp?

SAQEB MAHBUB asks the all-important question.

Although "Sangsad-ey ashun" or "Come to Parliament" is by far the most common rhetoric used by Awami League to undermine the opposition's efforts on the streets, it is perhaps unfair to characterise this as a sentiment solely shared by the ruling party. That the two major parties, along with their allies, will sort out their differences in the safe environment of Luis Kahn's beautiful structure is a dream shared by all. But why then have oppositions chosen the supposedly unpopular path of boycotting Parliament ever since the reinstatement of democracy? Why has the “free” airtime of BTV Sangsad not attracted the political opposition in the slightest? Is the JS really the political holy-ground that the opposition is blamed for boycotting?

This article attempts to delve into one of the major reasons for the apparent handicapped "growth" of our Parliamentary democracy and attempts to critically analyse the notion that our Parliament is a mere "rubber-stamp" to be used at the whim of the all-powerful executive.

Article 70 and MPs' "right (or lack of) to vote"

Anyone who may be watching proceedings of the Bangladesh Jatiya Sangsad with the hope of witnessing a fiery debate over a controversial bill or a nail-biting vote, might not find his time to be well-spent. The very idea of a parliament being a place where members come together and discuss an issue, try to convince fellow members to support their cause and then call for voting, is a concept alien to our parliamentary democracy. Bangladeshis have never even heard of a close vote in Parliament, let alone the government losing on a bill, no matter how unpopular a particular bill has been. No government has had to rally for public support on issues it has tried to push through the legislature. The question is, why would it have to, when it possesses the luxury of Article 70?

If one provision of law had to be singled out for its contribution towards holding back our otherwise promising parliamentary democracy, it would most certainly be Article 70 of the Constitution. Article 70 puts a bar on an MP from voting against his/her party in Parliament. Originally designed to prevent MPs from engaging in what is known as "floor-crossing", i.e. changing party loyalty after being elected, the barrier of Article 70 is not absolute, in the sense that an MP can still vote against his party. But, the fact remains that s/he can only do so at the high cost of losing his/her Parliament membership and therefore at the same time, ceasing to be a representative of his/her people.

Even after 15 amendments to the Constitution that was promulgated 40 years ago in 1972, Article 70 stands proudly and relatively unhurt, stating as follows:

"70. A person elected as a member of Parliament at an election at which he was nominated as a candidate by a political party shall vacate his seat if he

(a) resigns from that party; or (b) votes in Parliament against that party; but shall not thereby be disqualified for subsequent election as a member of Parliament."

The wording of sub-section (b) has hardly been critically questioned in the mainstream media. But if it was, perhaps some questions would have come to the fore, for instance: (a) is an MP bound by Article 70 even if his/her party does not express its stance before voting begins? (b) who makes the decision as to how the members are bound to vote -- the parliamentary party, i.e. the MPs of the party, or the central executive committee who are not necessarily elected or transparent? (c) can an MP belonging to a particular party in an electoral alliance vote differently from other members of the alliance? (d) can a party expressly permit its members to vote as they wish despite Article 70?

Subtle ambiguities, however, have had no bearing on ground reality. None except one MP, so far, has taken the leap against Article 70. The practical effect of this arrangement has been that, sadly, since the very inception of our country, successive governments have used our Parliament only as a rubber stamp to validate or legalise its pre-determined actions. No party in power has feared the Parliament as a battleground where they can be defeated by the opposition or even public sentiment for that matter. Not only does the opposition never stand a practical chance of winning a vote against the government, no critic inside the ruling party holds any bargaining power against an unreasonable or harmful decision of the government. A ruling party MP speaking against the government is free to speak his mind on the Parliament floor but the freedom ends once the Speaker calls for votes. From the moment vote is called, a Member of Parliament, the representative of the people, must only blindly follow the commands of his/her superiors in the party.

A subcontinental problem?

Interestingly, Bangladesh is not the only country with draconian restrictions on its MPs; her colonial cousins India and Pakistan have both incorporated provisions similar to Article 70 albeit with significant exceptions.

The Tenth Schedule of the Constitution of India while defining "defection" states that a member of parliament will lose his/her seat if s/he votes or abstains from voting:

"…contrary to any direction issued by the political party to which he belongs or by any person or authority authorised by it in this behalf, without obtaining, in either case, the prior permission of such political party, person or authority and such voting or abstention has not been condoned by such political party, person or authority within fifteen days from the date of such voting or abstention."

The provision would suggest, firstly, that there must be an express "direction issued" by the party, meaning that in the situation that the party does not "issue" a "direction" upon its members, they can vote as they wish. Secondly, to avoid losing their seat, an MP has the option of seeking permission to vote against the issued direction. Thirdly, even if they fail to obtain permission prior to the voting, they still have the option of applying for condonation within 15 days of voting.

Article 63A of the Pakistani Constitution, the provision that deals with disqualification of parliament members, provides even wider exceptions to the general rule of party-line voting. The restriction on the member's voting or abstention is limited to three situations only: (i) election of the Prime Minister or the Chief Minister; (ii) a vote of confidence or a vote of no-confidence; or (iii) a Money Bill or a Constitution (Amendment) Bill. Although the three situations protected by the restriction covers most bills which are likely to be critical and controversial, in terms of numbers, the members are free to vote according to their conscience on most bills.

The residual freedom in the Indian and Pakistan constitutions are certainly theoretical improvements from what we possess in Article 70, despite our recent amendment lifting the restriction on abstention (i.e. now MPs in Bangladesh can abstain from voting regardless of their party decision), but for true free-flowing parliamentary democracy to flourish, anything less than complete freedom to vote is insufficient.

Democracy hits brick wall

At its simplest core, democracy means government of the "demos" or people. The two other notions -- democracy by the people and democracy for the people -- then automatically follow, illustrating that the reach of the "demos" in governing the state does not stop at the point where they have chosen the representatives to protect their interests in the legislature. Rather, constant checks and balances must exist to ensure that those representatives are constantly representing the interests of the people and working for them.

In our system of parliamentary democracy, however, the power of the people ends at election time when they have chosen their delegates to the legislative assembly. Once an MP is elected, they have no further legal obligation to vote in Parliament as their voters direct, instead, our Constitution dictates that directions to be obeyed by them are to come from the party that nominated them. No matter how much a representative of the people may be influenced by their constituents, or regardless of how much their conscience may beg of them to contradict a party decision, they must follow their party superiors. Democracy then hits a brick wall.

As the Parliament plays little role in the "making" of a law and only assumes the role of "passing" it, one of the very basic principles of our Constitution, separation of powers, crumbles. A basic feature of our Constitution as declared in judgements of our apex court is the separation of the powers of the three organs of the State, namely, the legislature, the executive and the judiciary. Yet, the executive goes to Parliament with its "cabinet approved" bills and whizzes them through the House. Parliament rarely scrutinises or corrects, as if it is not an organ of the State but an organ of the executive itself.

Recent examples have illustrated the consequences of concentrating power in the hands of party high-ups instead of the elected lawmakers. Sensitive and nationally significant laws have been masterminded in a closed-door party forum and then passed in Parliament hurriedly and amid opposition from the ruling alliance's own ranks.

The Constitution (Fifteenth Amendment) Bill 2011 was passed in the face of fierce principled opposition from Awami League's leftist allies; they had proposed amendments, debated on the floor, but to no avail. Only minutes later, they were all found to go through the "YES" door, silently complying.

The Local Government (Amendment) Act 2011, dividing the Dhaka City Corporation, was passed in four minutes after a set of amendments to the bill proposed by an independent lawmaker was quickly gunned down by the ruling majority. The bill was hugely unpopular and it was hardly given any time for discussion either in Parliament or for public discussion in the media. But most unfortunately, the party in power did not even seek the opinion of their own MPs, the very people who were made to vote for the controversial split.

When such is the reality of our parliamentary democracy, is the government's call for the opposition to avoid the streets and join parliament really a genuine invitation to come to solutions? The present government, when exercising the power of its brute majority in Parliament, has even discarded the voice of its electoral allies when it came to pushing through their agenda on constitutional change. If the rules of play remain as they are, it is impossible by all means that if the opposition is to place a bill on the table, be that of a neutral caretaker government or anything else, it would pass without express support of the government. It would take a simple closed-door decision of the ruling party to bin any such proposition if it so wishes. There need not be any debate on the floor, no persuading to be done. Any bill, whoever may bring it, would be at the mercy of the government, thanks to Article 70.

Parliament needs to redeem its true purpose

When an ordinary person narrates the passing of a law using the language "government/X political party/the Prime Minister has passed a law", one may not bother to correct them and say that it is not the government or the Prime Minister or a political party that passes law, it is the Parliament that does so. The obvious reason for the free-flow of such language is that, for all practical purposes, when the government or the party in power has formed its opinion on a bill, passage of the bill in Parliament becomes a mere formality, an inevitable logical consequence. The all-important decision of whether a law will be passed or not is, in practice, either made in the Prime Minister's Office or the Cabinet (even the Cabinet's power seems to be minimal at times in the presence of the panel of the PM's advisers).

As MP's are stripped of their substantive law "making" duties in Parliament, most of them have to resort to being undeclared "administrators" in their own constituencies, exerting control over the civil administration and local politics, instead of discussing important national issues in Parliament. Those not within the "loyal circle" that runs the country have little to say about national policy and must resort to carrying out local development work to remind their voters of their presence. Sadly, neither has MPs spoken out against the prevailing situation nor has the government loosened its grip on what happens in Parliament. The government, instead, fuels the status quo by giving MPs immense control over how state resources are to be distributed in their local constituencies.

Such circumstances are deeply unfortunate for a country which has fought for the establishment of democracy more than once in its history. A ruling elite still exercises almost boundless power, for good or bad, at the expense of the people and the opposition of the day. A provision like Article 70 not only immunises the elite from interference in the implementation of its agenda, such a provision creates the unwanted distance between the people, their elected representatives and national policy-making.

Maintaining the status-quo of a dysfunctional parliament serves the interest of none except the undemocratic forces. Unless true bi-partisan parliamentary democracy can be established and Parliament can be shown to be an effective law-making body, the people of Bangladesh will always apprehend instability every time power is about to change hands. It is the brutal exercise of unfettered majority power in Parliament that leads the opposition of the day to the streets, whether in the form of peaceful rallies or violent hartals.

For the development of proper parliamentary democracy, Parliament must lose its image of being the ruling party's backyard. The fact that the opposition is an indispensable part of Parliament must be appreciated by the parties in government and opposition, and as such the conditions required to make its role a meaningful one must be fulfilled. As long as Parliament serves the purposes of the party in power and that party only, no opposition will be drawn by the idea of wielding its power of public support on Parliament premises where it is bound to be defeated by the existing majority. As long as Article 70 shields the government's interests in Parliament, the opposition has no substantive purpose there. And then, one could say, Parliament has no purpose. Therefore, to lay the foundations of a healthy, functional Parliament, Article 70 and the irrational restriction on the conscience of its members must be abolished at any cost.

But one must be realistic; the long followed practice of party-line voting will not disappear in a day with the simple abolition of a constitutional provision. To carry forward the cause of establishing a vibrant Parliamentary culture, change must flow from the top. Backbencher MPs must be assured of no adverse political consequences for voting as they wish and the opposition must be promised a chance of persuading the House to vote for its proposals. Only then will Parliament stop being a government-controlled playing field and be more than a rubber-stamp of the executive. Only then will lawmakers be able to do what they are elected to do and only then will the rhetoric of "Sangsad-ey ashun" or "Come to Parliament" bear true meaning.

Special thanks to Ashikur Rahman, Barrister Imam Hossain Tareq and Barrister Nuara Choudhury for their extremely valuable input on this article.

Saqeb Mahbub is Barrister-at-Law and can be reached at saqebmahbub@gmail.com.