| |

A

Tradition That's Trendy A

Tradition That's Trendy

Shamim Ahsan and Kajalie Shehreen Islam

What is known as khadi

today was produced and used for years by the middle

and working classes of the sub-continent in the 19th

century, especially during the Swadeshi movement. The

turning point, however, came in the 1920s with Mahatma

Gandhi's Non-Co-operation Movement. One provision of

this non-violent movement was to produce and use only

local goods, including homemade clothing, i.e., khadi.

Gandhi gave the art of khadi a special status

through this movement, writes Bijon Guha in his article,

"Khadi Ebong Amar Jibon" ("Khadi

and My Life” in a brochure for Kay Kraft's khadi Utsab).

After the two movements, however, the popularity of

khadi cloth came down.

Khadi is, however, unique. Its basic definition,

say experts, is that it is hand spun and hand woven.

"The difference between khadi and handloom

is apparent in the texture," says Ruby Ghuznavi

of Arannya and President of National Craft Council.

"Handloom is smooth while khadi is uneven."

Real Khadi can only be made from cotton yarn,

says Ghuznavi. Muslin was a kind of khadi when

the yarn was very, very fine, she says, but you can't

get that kind of finesse anymore. What we have now is

the kind Gandhiji wore -- thick khadi. "Real

khadi has to be uneven, unless it's fine khadi,"

says Ghuznavi.

Many

khadi wholesalers and retailers complain that

dyed khadi will always have blotches of colour,

or uneven shades within the same thaan. But

Ghuznavi says that it is only when the yarn is dyed

before weaving and not the whole thaan that

the colour comes out in uneven shades. "It doesn't

have to be this way", she says. " It wasn't

this way when Guha Babu was alive."

In

Bangladesh, no one can speak of khadi without

referring to Shoilendranath Guha, probably the biggest

contributor to the art of khadi and natural dye.

"I

ordered 12,000 metres of khadi thaan from Guha

Babu," recalls Ruby Ghuznavi, "and he fulfilled

the order perfectly. I wouldn't dare do it today because

I know it won't be done right. They cannot do it."

Today, the khadi tradition

is being carried on by his sons, namely, Bijon and Arun

Guha. Spun by weavers in Chandina, Guha's descendants

seem to be the only ones producing khadi in Bangladesh

supplying various outlets and organisations with the

material.

"Shoilen

Guha wanted the Bangladeshi flag to be made of khaddar,"

reminisces Shahid H. Shamim, Director of prabartana.

"He did make some, but if the government took steps

for all our flags to be made of khadi, it would

be something."

Shoilendranath Guha believed

that a big industrial revolution could be brought about

with khadi. Khadi production is human-resource based,

says Shamim. Its popularity and thus increased production

would mean the employment of thousands of weavers.

Sadly,

however, weavers are changing professions, moving on

to better-paying jobs, and in the process, we are losing

the art of weaving. Sadly,

however, weavers are changing professions, moving on

to better-paying jobs, and in the process, we are losing

the art of weaving.

Throughout the second half

of the 20th century, use of khadi fell consistently.

Towards the early nineties, however, khadi made a sudden

and strong comeback, thanks to a number of fashion houses

like Aarong, Kay Kraft, Prabartana, Arannya and many

others who have successfully synchronised technology

with heritage by complementing the local weaving industry

with modern machinery.

The survival of khadi and subsequent

rise in its popularity has been significant both in

terms of heritage and economy. Khadi has been very much

a part of our life and lifestyle, and in its hundreds

of years of expansion it holds the history of a people's

evolution, their struggle, their joys and tears.

On the economic front, khadi's growing

acceptance since the early nineties has at least kept

our local weaving industry going in a market that has

been made free unscrupulously and consequently flooded

with Indian goods. In the last ten years or so, these

fashion houses have succeeded not only in bringing khadi

back into the mainstream -- though in a very small way

-- but, more importantly, in exploiting the originality

of khadi by turning out khadi clothes into fashion wear.

Kay

Kraft's Khadi Utsab Kay

Kraft's Khadi Utsab

Kay Kraft is one of the leading houses

that have contributed to this rescue act of khadi. Since

its early days, Kay Kraft has taken it upon itself to

provide khadi a much-needed platform and to help it

blossom to its full potential. Those associated with

Kay Kraft have scoured the country discovering, talking

to and motivating the ever shrinking, endangered community

who have been working with khadi for generations. At

one point, Khalid Mahmud Khan, Director of Kay Kraft,

met Shoilendranath Guha -- an extremely respected name

in the khadi industry -- in Chandina, Comilla.

"The meeting was crucial for Kay

Kraft," says Khan. "We had heard a lot about

this man -- his struggle, sincerity and devotion to

the khadi industry. As we met we talked about khadi,

its problems and strengths." When taking leave,

Khan invited Guha to his home and could hardly believe

his luck when Guha visited him in just seven days. "He

requested us to work with khadi and though we had already

begun, his request made a great impression on our minds,"

says Khan. "We felt extremely inspired and motivated

and embarked upon our goal with renewed energy,"

he reminisces. Guha's request and Kay Kraft's efforts

did not go in vain.

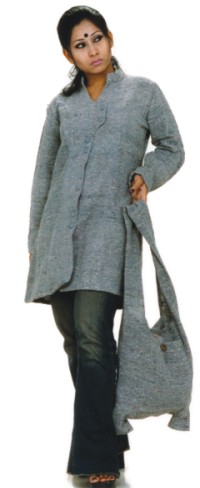

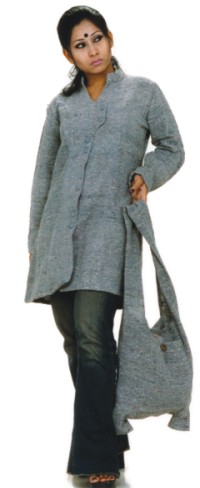

It wasn't easy, though. One of their

first challenges was to prove wrong the popular notion

that khadi was only a poor man's garment. The somewhat

rough texture, uneven finishing and, above all, the

dull designs made khadi rather unattractive and failed

to appeal to the fashion-conscious youth.

"Our

first job at hand was to show that, if creatively done,

khadi products can also be appealing and of high

standards. When we started, punjabis and fotuas

were still village people's get-up; the urban middle

class were not very fond of it. Our first venture with

khadi was to use it in punjabis and

fotuas and our products were received extremely

well by customers. While we were attentive to design,

we also experimented on a kind of amalgamation, sometimes

by combining silk with khadi and sometimes mill-produced

fibre. The initial success boosted our confidence and

we are now doing a lot more experimentation to develop

new designs," Khan relates.

Khadi,

because it is hand spun and hand woven, has its own

distinct quality. "While developing new designs

we have always endeavoured to keep khadi's characteristics

intact," says Khan. "Even when we mix silk

and artificial fibre with khadi, we do it in

a way so that the end product does not lose the khadi

touch, rather it brings out its effects," Khan

says, explaining the main feature of their design.

Khan also believes that khadi is more

expressive and designers have a lot more to do with

the material. "The coarse texture of khadi provides

a wider scope to experiment with design. Its distinct

nature gives the space to use your creativity more than

fine-textured artificial fibre," says Khan. "Again,

mixing silk or other varieties with khadi gives one

the opportunity to play with the weaving designs like

putting the different fibres in different combinations,

changing their frequency and density here and there,"

Khan explains, referring to textile designing.

Khadi

is our heritage, connected with our soil and lifestyle

and it has lived on for hundreds of years across generations.

Fortunately, many fashion houses felt they must try

to save our heritage at all costs. "When we established

Kay Kraft we wanted to create a niche in fashion wear

by developing our own style," says Khan. "You

cannot claim originality borrowing others' things and

depending on foreign ideas, so khadi was our

automatic choice. From a business point of view khadi

was also the preferred choice. If people get trendy,

good quality khadi products they will certainly

prefer them to foreign ones and won't even mind paying

a little more. So khadi serves both purposes

-- of satisfying the demand of fashion as well as making

people proud of wearing local products. And this is

where lies Khadi's potential," Khan says. Khadi

is our heritage, connected with our soil and lifestyle

and it has lived on for hundreds of years across generations.

Fortunately, many fashion houses felt they must try

to save our heritage at all costs. "When we established

Kay Kraft we wanted to create a niche in fashion wear

by developing our own style," says Khan. "You

cannot claim originality borrowing others' things and

depending on foreign ideas, so khadi was our

automatic choice. From a business point of view khadi

was also the preferred choice. If people get trendy,

good quality khadi products they will certainly

prefer them to foreign ones and won't even mind paying

a little more. So khadi serves both purposes

-- of satisfying the demand of fashion as well as making

people proud of wearing local products. And this is

where lies Khadi's potential," Khan says.

Over the last decade, khadi goods have

come a long way both in terms of quality and design.

What has made various fashion houses like Kay Kraft

or Prabartana or Arannya succeed is their ability to

adapt their khadi products to contemporary tastes. "We

have always been very sensitive to changing trends and

experimented with new ideas in our products," says

Khan.

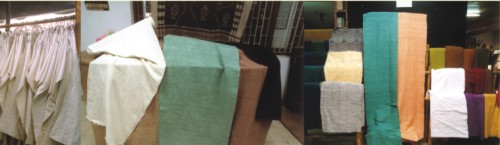

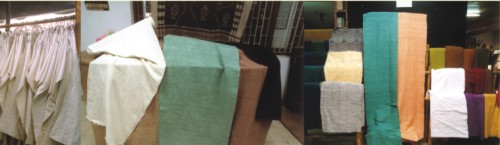

One particular change has been the diversification

of products. For a long time the use of khadi was confined

to only a few items like punjabis, kurtas and

kotis, so Kay Kraft recently began experimenting

with other products as well. The Khadi Utsab, held from

January 15 to 18 of this year arranged by Kay Kraft

was in fact the result of their experimentation with

specially developed products with some very creative

designs. "We had a whole variety of khadi products

including sarees and shalwar kameezes where

we tried to explore new ideas in terms of design,"

explains Khan. The four-day long festival drew a large

number of visitors and Khan adds that they spoke very

highly of the products.

***

THE problem with khadi isn't the market,"

claims Ruby Ghuznavi. "There is a big enough market

for pure khadi compared to the production. The problem

is that production of genuine khadi is low and definitely

not enough for export."

Much of what is sold as khadi in our

country today is fake, says Shahid H. Shamim. That is,

it is not hand spun and hand woven but produced in machines

and mills. "Many of the punjabis and other khadi

cloth sold are hardly khadi," he says.

"Most people don't buy khadi because

it's khadi," says Ghuznavi. "They buy it because

they like it." So why not sell khadi as khadi and

handloom as handloom? Blending is fine, agree both Ghuznavi

and Shamim, as long as it remains pure khadi, that is,

as long as it is, in fact, hand-spun and hand-woven.

Among silk, however, says Ghuznavi, only endy

silk is hand-spun from caster leaves and so combination

with any other variety of silk is not really khadi.

Arannya

itself mainly produces curtains made of khaddar

for export, as well as accessories such as scarves along

with Western wear. The market is good enough, Ghuznavi

believes, but to compete in the foreign market, we cannot

just accept things like "the colour will be uneven

and this will be like this" and so on.

"At Prabartana we are making souvenir

scarves with yarn made from jhum cotton from

the hill tracts," says Shamim. "We are also

experimenting with fine khadi which is not available

here and which we will be exporting to countries like

Japan. It is still at the development stage, however,"

says Shamim.

"Indigenous societies in our country

also make a green cotton, that is, there are no chemicals

in it," adds Shamim. "If we could market this

abroad, it could also be quite profitable."

Sarwat Abed, Director of Aarong, puts

emphasis on the diversification of khadi goods. "If

we cannot multiply khadi products and create a bigger

market all our sincere efforts to support and patronise

the local looms will fail," she says. She however

admits that Aarong has not worked extensively with khadi

in recent times and at the moment does not have a huge

collection. "But we have our plans. At the moment

we are doing a lot of research work and our designers

are working to develop new khadi products and designs,"

Abed assures. She says that Aarong is also working on

making household products along with the traditional

khadi apparel such as punjabis, shawls, fotuas,

tops, etc.

What we need more than a market for

khadi is to create awareness, inform people and promote

genuine khadi, says Ruby Ghuznavi. And we need to increase

production. If Guha Babu was alive today, she says,

he would have expanded the production to five times

its present size, involving more spinners and weavers

and building a huge market.

Every

patron of khadi will quote the Late Shoilendranath

Guha as saying that if we all used one khaddar payjama-punjabi

a year, it would do wonders -- for ourselves, the tradition

and the country. In Shoilen Guha's own words, "Apnara

ei khaddar kapor babohar kore khaddar shilpoke bachiye

rakhun." Use khaddar cloth and keep the art

alive.

|

|

A

Tradition That's Trendy

A

Tradition That's Trendy

Sadly,

however, weavers are changing professions, moving on

to better-paying jobs, and in the process, we are losing

the art of weaving.

Sadly,

however, weavers are changing professions, moving on

to better-paying jobs, and in the process, we are losing

the art of weaving. Kay

Kraft's Khadi Utsab

Kay

Kraft's Khadi Utsab Khadi

is our heritage, connected with our soil and lifestyle

and it has lived on for hundreds of years across generations.

Fortunately, many fashion houses felt they must try

to save our heritage at all costs. "When we established

Kay Kraft we wanted to create a niche in fashion wear

by developing our own style," says Khan. "You

cannot claim originality borrowing others' things and

depending on foreign ideas, so khadi was our

automatic choice. From a business point of view khadi

was also the preferred choice. If people get trendy,

good quality khadi products they will certainly

prefer them to foreign ones and won't even mind paying

a little more. So khadi serves both purposes

-- of satisfying the demand of fashion as well as making

people proud of wearing local products. And this is

where lies Khadi's potential," Khan says.

Khadi

is our heritage, connected with our soil and lifestyle

and it has lived on for hundreds of years across generations.

Fortunately, many fashion houses felt they must try

to save our heritage at all costs. "When we established

Kay Kraft we wanted to create a niche in fashion wear

by developing our own style," says Khan. "You

cannot claim originality borrowing others' things and

depending on foreign ideas, so khadi was our

automatic choice. From a business point of view khadi

was also the preferred choice. If people get trendy,

good quality khadi products they will certainly

prefer them to foreign ones and won't even mind paying

a little more. So khadi serves both purposes

-- of satisfying the demand of fashion as well as making

people proud of wearing local products. And this is

where lies Khadi's potential," Khan says.