|

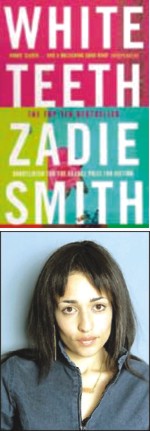

Book

Review

After

Post-colonialism

John

Mullan

It will

be interesting to see if the fastest growing branch of literary

studies in Britain over the past decade - post-colonialism

- decides that Zadie Smith belongs to its terra nova or not.

Out in the universities, where academics may happily use vocabularies

intelligible only to initiates, "post-colonialism"

is the heading for a large number of courses and accompanying

primers of dense literary theory. It is under this heading

that literature and ethnicity are invariably discussed, often

with a special critical terminology: "hybridity",

"subaltern", "the Other".

Well,

White Teeth is certainly about ethnic identity (or

confusion) and the latterday consequences of colonialism.

It is colonialism that has brought almost all the characters

to London, and they are sometimes conscious of their post-colonial

identities. Samad Iqbal, the waiter with higher aspirations,

is proud of his descent from Mangal Pande, executed by the

British in the first phases of the Indian Mutiny of 1857.

Hortense Bowden, Jamaican stalwart of the Lambeth Jehovah's

Witnesses, was fathered by an English officer, posted to the

West Indies, on his landlady's daughter. Well,

White Teeth is certainly about ethnic identity (or

confusion) and the latterday consequences of colonialism.

It is colonialism that has brought almost all the characters

to London, and they are sometimes conscious of their post-colonial

identities. Samad Iqbal, the waiter with higher aspirations,

is proud of his descent from Mangal Pande, executed by the

British in the first phases of the Indian Mutiny of 1857.

Hortense Bowden, Jamaican stalwart of the Lambeth Jehovah's

Witnesses, was fathered by an English officer, posted to the

West Indies, on his landlady's daughter.

Yet the

ethnic and cultural identities of the characters are so various

that Smith seems to be taking and enjoying new liberties rather

than plotting the consequences of empire. Much of the book

is devoted to a Bangladeshi family and Smith (daughter of

a Jamaican mother and an English father) has no hesitation

about taking us into the inner world of its would-be patriarch,

musing on his failed attempts to pass on his culture. The

son he keeps in England turns into a "fully paid-up green

bow-tie- wearing" Muslim fundamentalist. The son he sends

back to Bangladesh to imbibe the wisdom of the old country

"comes out a pukka Englishman, white suited, silly wig

lawyer".

Smith

has allowed herself a certain imaginative freedom. "All

the mixing up" of cultures and races allows her to mix

customs and vocabularies at will. Parents lie awake at night

foreseeing their "unrecognisable great-grandchildren...

genotype hidden by phenotype". But the odd mixes go on.

They come alive in Smith's dialogue, where we hear the English

language comically accommodating every new pressure and habit.

In one

way, this is characteristic of "post-colonialism"

as a type of literature: fiction and poetry in English written

by citizens of former colonies, or by British citizens who

are immigrants or the children of immigrants from those colonies.

The label has replaced "Commonwealth literature",

with its implication of grateful subjects creatively repaying

their debts to British civilisation.

White

Teeth is full of jokes about odd couplings of cultures.

Thus its cameos of what we might call "post-colonial

cuisine". Once, Archie told Samad what he fought for

in the war: "Democracy and Sunday dinners, and... promenades

and piers, and bangers and mash - and the things that are

ours". But eating becomes something much stranger in

modern England, the land, as Samad reflects, of "terrible

food".

Then there

is the surreal anecdote about Australian cooking in Willesden.

"After a complaint of a terrible smell above Sister Mary's

Palm Readers on the high road", health officers found

"sixteen squatting Aussies who had dug a huge hole in

the floor and roasted a pig in there, apparently trying to

recreate the effect of a South Seas underground kiln".

You might indeed read it in your local paper.

So many

differences, yet Irie, denizen of a multi-ethnic suburb, where

children are called Isaac Leung and Quang O'Rourke, is free

to moan: "Everyone's the same here". She wants to

take a year off before university so that she can go to "the

subcontinent and Africa (Malaria! Poverty! Tapeworm!)".

She wants "some experiences". Suburbia is just suburbia,

after all. Is this post-post-colonialism?

John

Mullan is senior lecturer in English at University College,

London. This article was first published in The Guardian.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2004

|